Mt Oakleigh. Jan 2018

A trip I was going to be on was cancelled due to bad weather, so I determined this was the weekend I would sleep on Mt Oakleigh. It would rain on my way up, but, hopefully, I’d get good views next morning. I checked the wind forecast, which was fine, and, just on the off-chance, dashed off a message to one of my IG friends, who said she’d like to come. An adventure was on.

I have done a bit of waterfall bagging with this friend, and we have fun together. I realised as we progressed along our way on Saturday, however, that this was her first overnighter with a tent, that she was feeling a bit nervous, and that perhaps climbing a mountain on your first attempt at sleeping in the wild was maybe a bit too wild. I offered her the alternative that if she was too worried about the conditions up there (they didn’t look at all friendly from below), then I’d go with her to New Pelion Hut, and then climb the mountain alone. No, no. She wanted to come. On we continued. It was nice that she trusted me to keep her alive, as a wild mountain is a rather confronting beast when you meet it face to face. Secretly, I was worried about her lack of equipment in the face of the cold weather up there, but I was also pretty sure I could help her through a crisis. Her lycra tights were not keeping her at all warm. She had no beanie, and no spare shoes, but she did have dry socks for overnight, and a decent sleeping bag. My tent takes two at a pinch, so if she was freezing, I could invite her into mine to warm up.

I have done a bit of waterfall bagging with this friend, and we have fun together. I realised as we progressed along our way on Saturday, however, that this was her first overnighter with a tent, that she was feeling a bit nervous, and that perhaps climbing a mountain on your first attempt at sleeping in the wild was maybe a bit too wild. I offered her the alternative that if she was too worried about the conditions up there (they didn’t look at all friendly from below), then I’d go with her to New Pelion Hut, and then climb the mountain alone. No, no. She wanted to come. On we continued. It was nice that she trusted me to keep her alive, as a wild mountain is a rather confronting beast when you meet it face to face. Secretly, I was worried about her lack of equipment in the face of the cold weather up there, but I was also pretty sure I could help her through a crisis. Her lycra tights were not keeping her at all warm. She had no beanie, and no spare shoes, but she did have dry socks for overnight, and a decent sleeping bag. My tent takes two at a pinch, so if she was freezing, I could invite her into mine to warm up.

Her voice became a bit more anxious when she realised that I had not camped up here before, and that I didn’t have a clue whether we would find a spot, as I don’t know anyone who has ever camped there. “What happens if there’s nowhere to camp?”, she enquired. “Then we come back down,” I replied, which was not, I presume, good news when you are already very tired, but that is always my plan.

Her voice became a bit more anxious when she realised that I had not camped up here before, and that I didn’t have a clue whether we would find a spot, as I don’t know anyone who has ever camped there. “What happens if there’s nowhere to camp?”, she enquired. “Then we come back down,” I replied, which was not, I presume, good news when you are already very tired, but that is always my plan.

“What is there’s no water on top?”

“Then I come back down to collect it for both of us.” That answer was more welcome. “That’s why I keep pointing out sources of water when we pass them, as I am timing how long from the last seen water to the top in case I do have to do that. And I have never yet failed to find some way of pitching two tents on top. One just has to be creative.”

That sounded good, but there does surely, have to be a first time when there is absolutely nothing. I didn’t add that.

The conditions for pitching up there were not exactly five-star quality, and my friend quite justifiably wanted to be near me for security, so we were looking for flat ground for two that did not exist. We found the best available real estate, which would not have sold for much as it was merely a patch of bush where the scrub was not too prickly or tall. We threw our tents over the bushes, pinning the corners to the ground, and somehow managed to get a quarter decent pitch that would stay up all night. Both of us had tent floors that followed an artistic wave pattern. I actually found my wave quite comfy, as it was at least soft, and one of the ups acted as a pillow.

The conditions for pitching up there were not exactly five-star quality, and my friend quite justifiably wanted to be near me for security, so we were looking for flat ground for two that did not exist. We found the best available real estate, which would not have sold for much as it was merely a patch of bush where the scrub was not too prickly or tall. We threw our tents over the bushes, pinning the corners to the ground, and somehow managed to get a quarter decent pitch that would stay up all night. Both of us had tent floors that followed an artistic wave pattern. I actually found my wave quite comfy, as it was at least soft, and one of the ups acted as a pillow.

It was almost a relief that sunset was a fizzer, as we both had truly frozen feet, and the only thing either of us could think of was the joy of taking off wet boots and socks and getting into a dry sleeping bag. If anything good happened to the mountains out there at dusk, we don’t know about it.

It was almost a relief that sunset was a fizzer, as we both had truly frozen feet, and the only thing either of us could think of was the joy of taking off wet boots and socks and getting into a dry sleeping bag. If anything good happened to the mountains out there at dusk, we don’t know about it.

The wind flapped our tents all night. Neither of us got any substantial sleep, so the alarms for sunrise at 5.15 were not exactly welcome. I poked my head out. “Na. No colour. I’m ‘sleeping’ for another 20.”

The wind flapped our tents all night. Neither of us got any substantial sleep, so the alarms for sunrise at 5.15 were not exactly welcome. I poked my head out. “Na. No colour. I’m ‘sleeping’ for another 20.”

At 5.35 there was a tiny hint of pink, so I felt obliged to go out and see if anything nice could happen. It did, and we were both happy with our results. Now that she had survived her first night out, and on a mountain at that, my friend was very happy. We both walked well on the return journey, and were back at the car before midday, keen for our next adventure. I learned that after a night like that, I should have cappuccino before driving the solo section. I fell asleep at the wheel a mere kilometre from home. Luckily, I was fighting sleep so hard that I was only doing about 35 kms/hr just in case, and, more luckily, there was no oncoming traffic, as my steering swerved me to the right of the road once I dropped off. It is very, very unnerving to do this. You have the insane belief that if you fight sleep, you can win. I am still in a bit of shock, even though no harm came of it.

Another sad theory that was tested this weekend was the one told to me by Telstra, namely, that 000 would work anywhere, as it uses a different wavelength. I got a flat tyre on the drive in, and needed RACT. There was no reception. 000 did not work. You are no doubt laughing at a stupid, stereotypical woman who can’t change a tyre. I know what to do, but there are a few problems: (i) I am not strong enough to pull the spare tyre out of its hole (ii) I cannot push the spanner to undo the nuts. I stood on it. Nothing happened. I jumped on it. Nothing (I weighed 43 kgs when I checked at Christmas [before the pudding ha ha]). I went to the very edge to get maximum leverage, and only then could I begin to budge it whilst jumping on it. The insurmountable problem, however, is that if I did somehow get the old wheel off, there is no way on this earth that I could lift the new wheel into place. Luckily, a good samaritan (well, two) happened to drive up (Ashley and Noelene), and they helped me, whilst instructing me at the same time, but realised along with me that if alone, I would not be capable of getting out of this fix, and the problem that 000 does not actually work all over Tasmania is rather daunting. There are places where one could starve hoping for a good samaritan to drive nearby.

Another sad theory that was tested this weekend was the one told to me by Telstra, namely, that 000 would work anywhere, as it uses a different wavelength. I got a flat tyre on the drive in, and needed RACT. There was no reception. 000 did not work. You are no doubt laughing at a stupid, stereotypical woman who can’t change a tyre. I know what to do, but there are a few problems: (i) I am not strong enough to pull the spare tyre out of its hole (ii) I cannot push the spanner to undo the nuts. I stood on it. Nothing happened. I jumped on it. Nothing (I weighed 43 kgs when I checked at Christmas [before the pudding ha ha]). I went to the very edge to get maximum leverage, and only then could I begin to budge it whilst jumping on it. The insurmountable problem, however, is that if I did somehow get the old wheel off, there is no way on this earth that I could lift the new wheel into place. Luckily, a good samaritan (well, two) happened to drive up (Ashley and Noelene), and they helped me, whilst instructing me at the same time, but realised along with me that if alone, I would not be capable of getting out of this fix, and the problem that 000 does not actually work all over Tasmania is rather daunting. There are places where one could starve hoping for a good samaritan to drive nearby.

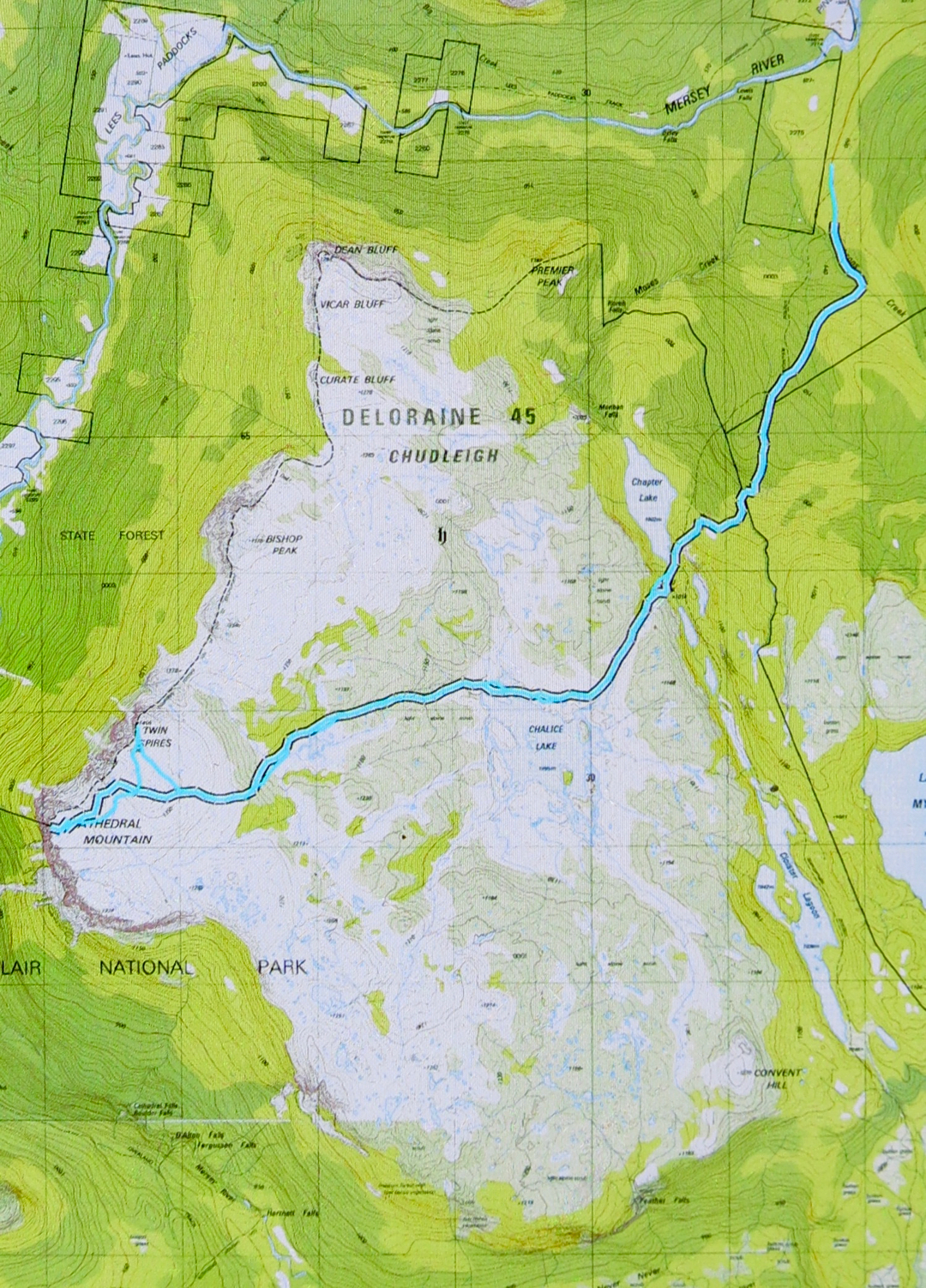

But you, lucky reader, can presumably visit this wonderful summit without these cares, and the majesty will have more power to impress you. Getting to the top involves a combination of track following and navigation. A rough (and not always distinct) path leads from the carpark at the end of the Lake Rowallan Road to the beautiful Grail Falls, after which a cairned route takes over, getting you as far as Tent Tarn. If you are not a confident navigator, you should stop here (or even earlier, by one of the other beautiful lakes). From Tent Tarn to the top, there is a route which is cairned, but the cairns are not always as close together as you might like and you do need to know what you’re doing in between their guidance. You need to be happy about branching out and not caring if you don’t find any more cairns today. (For the climb of the next day, Twin Spires, see separate post,viz:

But you, lucky reader, can presumably visit this wonderful summit without these cares, and the majesty will have more power to impress you. Getting to the top involves a combination of track following and navigation. A rough (and not always distinct) path leads from the carpark at the end of the Lake Rowallan Road to the beautiful Grail Falls, after which a cairned route takes over, getting you as far as Tent Tarn. If you are not a confident navigator, you should stop here (or even earlier, by one of the other beautiful lakes). From Tent Tarn to the top, there is a route which is cairned, but the cairns are not always as close together as you might like and you do need to know what you’re doing in between their guidance. You need to be happy about branching out and not caring if you don’t find any more cairns today. (For the climb of the next day, Twin Spires, see separate post,viz: