Mt Roland Apr 2017

I have wanted to sleep on Mt Roland for a very long time. I think the provenance of the desire dates back to seeing a full moon rising from just behind the mount as the sun was setting to our rear as we gazed. I decided sunset up there would be wonderful. That was many years ago, and somehow the chance has never quite come about.

However, just as I was about to leave the house to drive south and pick up my friend to climb Aldebaran together, I received an email saying he couldn’t come due to an emergency. Meanwhile, I had not been enjoying the turn the weather maps had been taking since we firmed up the arrangement, so now that I wasn’t expected to be there, I decided I didn’t want to drive all that way for a repetition of last weekend’s weather. BUT, there was the fact of my packed rucksack and all my emotions that were geared for a mountain climb. I couldn’t possibly do nothing. On the spur of the moment, I suggested to my husband that we at last try sleeping on Roland, despite the rather abysmal forecast. This one could be a recce, a little practice for the real one. I wouldn’t even take my full-frame camera and tripod for this trip, which was good, as I would be carrying the lion’s share of gear for us.

However, just as I was about to leave the house to drive south and pick up my friend to climb Aldebaran together, I received an email saying he couldn’t come due to an emergency. Meanwhile, I had not been enjoying the turn the weather maps had been taking since we firmed up the arrangement, so now that I wasn’t expected to be there, I decided I didn’t want to drive all that way for a repetition of last weekend’s weather. BUT, there was the fact of my packed rucksack and all my emotions that were geared for a mountain climb. I couldn’t possibly do nothing. On the spur of the moment, I suggested to my husband that we at last try sleeping on Roland, despite the rather abysmal forecast. This one could be a recce, a little practice for the real one. I wouldn’t even take my full-frame camera and tripod for this trip, which was good, as I would be carrying the lion’s share of gear for us.

He said he’d like that, so I spent about ten minutes throwing a few items of clothing into his pack, and off we set. My own rucksack was ready for a three-day trip, so I figured I had enough food and gas for two. Not a great deal of thought went into this packing, but I did double check that I’d tossed in enough warm garments for him.

He said he’d like that, so I spent about ten minutes throwing a few items of clothing into his pack, and off we set. My own rucksack was ready for a three-day trip, so I figured I had enough food and gas for two. Not a great deal of thought went into this packing, but I did double check that I’d tossed in enough warm garments for him.

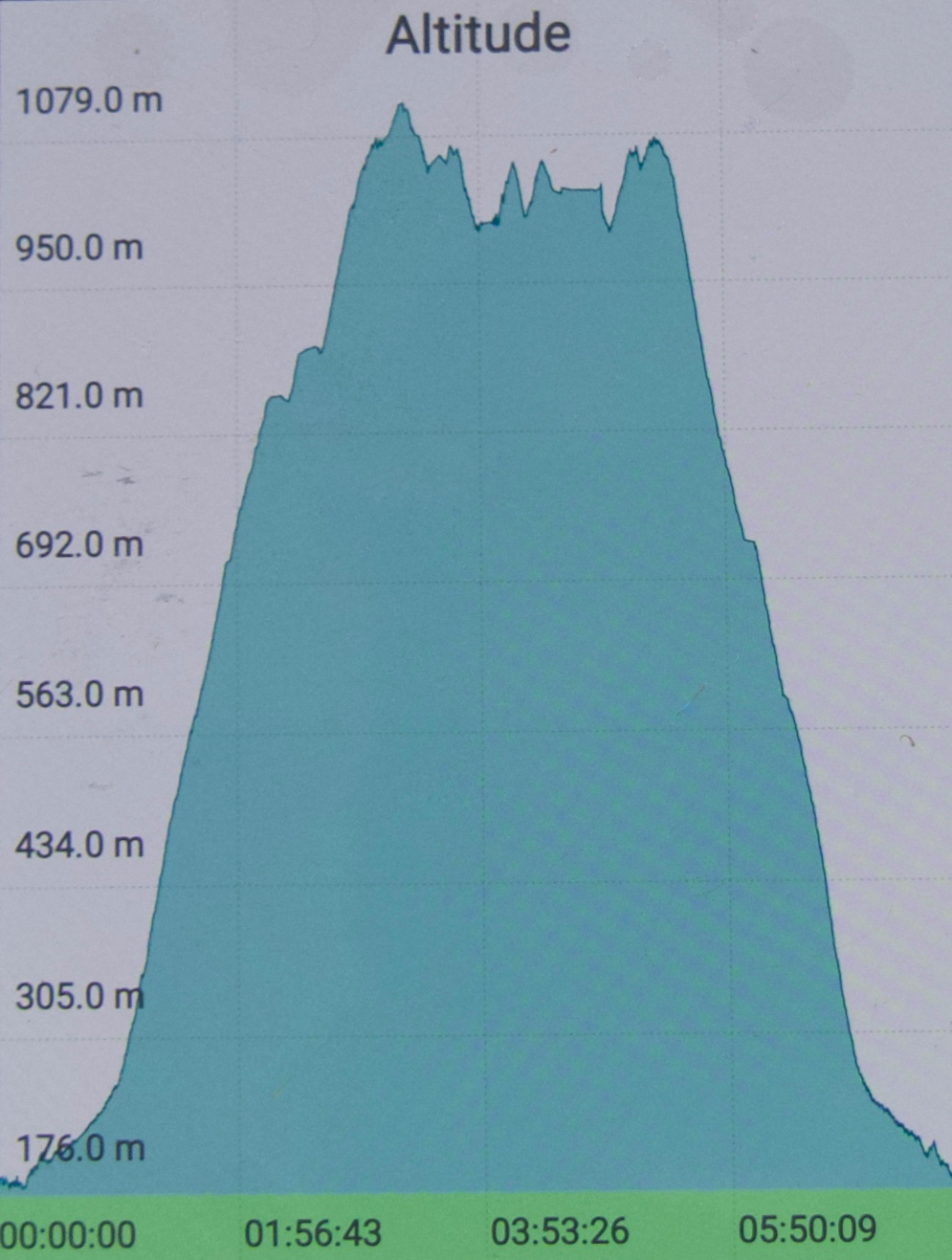

We didn’t get started until 4.15, which is rather late even for normal people. For a man with Parkinson’s disease, this is way too late for this mountain at this time of year, but we weren’t going to back out of this now. We’d be right, I thought optimistically. After 18 minutes, we reached a junction in the track that said that a fit walker could get to the summit in three hours from that point. Oh. It was now after 4.30, and we had a mere one hour of good light. Well, these signs always overestimate the time. On we pressed, hoping the information was very wrong indeed.

We didn’t get started until 4.15, which is rather late even for normal people. For a man with Parkinson’s disease, this is way too late for this mountain at this time of year, but we weren’t going to back out of this now. We’d be right, I thought optimistically. After 18 minutes, we reached a junction in the track that said that a fit walker could get to the summit in three hours from that point. Oh. It was now after 4.30, and we had a mere one hour of good light. Well, these signs always overestimate the time. On we pressed, hoping the information was very wrong indeed.

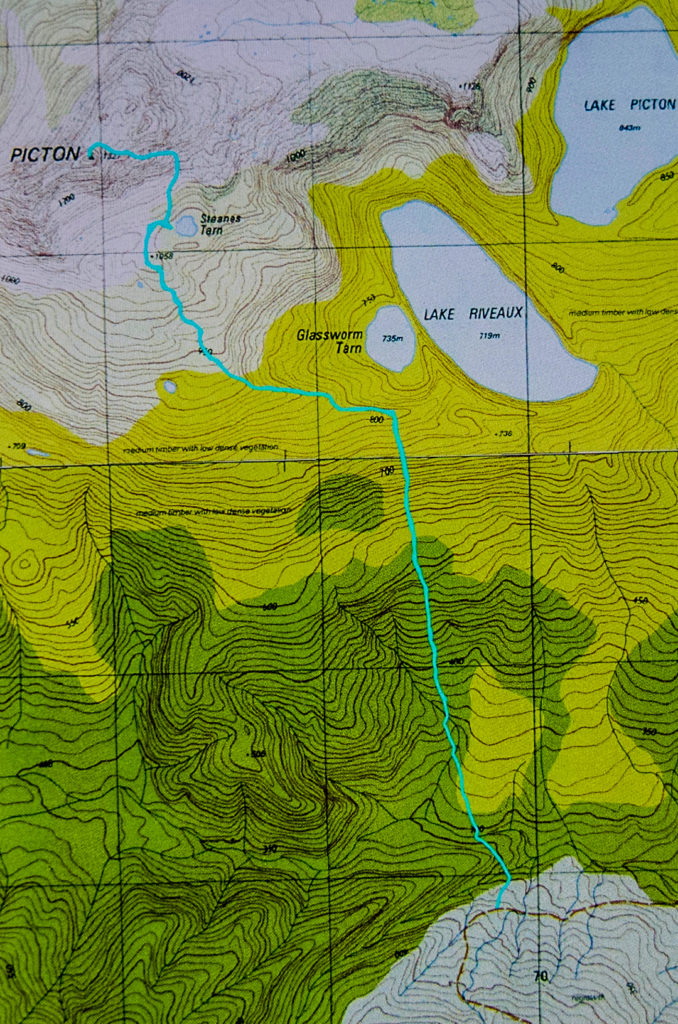

After 67 minutes from the car, we were at O’Neills Creek, and stopped for a quick drink. I looked at the map to see what lay ahead for the immediate future. Hm. Many, many contours lay ahead, although we seemed to have done most of the distance. I looked at the track on the other side of the creek and noted that I could see nothing at all. The forest was so dense there, and the clouds so thick above us, and the hour so very late indeed that there was zero visibility. However, I don’t come into the wilderness to camp three-quarters of the way up a mountain in a claustrophobic little gully. I didn’t really like this spot. I wanted the wide open spaces of the top. On we pressed, now in complete darkness, although it was only 5.25.

After 67 minutes from the car, we were at O’Neills Creek, and stopped for a quick drink. I looked at the map to see what lay ahead for the immediate future. Hm. Many, many contours lay ahead, although we seemed to have done most of the distance. I looked at the track on the other side of the creek and noted that I could see nothing at all. The forest was so dense there, and the clouds so thick above us, and the hour so very late indeed that there was zero visibility. However, I don’t come into the wilderness to camp three-quarters of the way up a mountain in a claustrophobic little gully. I didn’t really like this spot. I wanted the wide open spaces of the top. On we pressed, now in complete darkness, although it was only 5.25.

Miraculously, given Bruce’s illness, we arrived up the top safe and sound, but it was by now very dark indeed, and not just in the deep forest. However, I could feel the icy air circling around me, and it was exhilarating. This thin air is what I love, even when I can’t see a thing. I can feel the infinite space that exists on the tops. I was happy. There’s not much choice arriving like this in the dark. I had no idea how I was going to find a spot to pitch. We were carrying enough water to do dinner and breakfast (which was absurd, as water was everywhere, but at least collecting it was not one of my duties that night), so were not tied to a water source.

Miraculously, given Bruce’s illness, we arrived up the top safe and sound, but it was by now very dark indeed, and not just in the deep forest. However, I could feel the icy air circling around me, and it was exhilarating. This thin air is what I love, even when I can’t see a thing. I can feel the infinite space that exists on the tops. I was happy. There’s not much choice arriving like this in the dark. I had no idea how I was going to find a spot to pitch. We were carrying enough water to do dinner and breakfast (which was absurd, as water was everywhere, but at least collecting it was not one of my duties that night), so were not tied to a water source.

I pitched for us and cooked in the vestibule, and we ate our rehydrated dehydrated food in the warmth of my little Hilleberg, agreeing that this was the life. Howling wind now provided background noise to our conversation. It could be heard all night.

I pitched for us and cooked in the vestibule, and we ate our rehydrated dehydrated food in the warmth of my little Hilleberg, agreeing that this was the life. Howling wind now provided background noise to our conversation. It could be heard all night.

Sunrise next day was far better than one could ever have hoped for, especially given the thick clouds of the previous evening. We enjoyed the spectacle, and then breakfasted before heading for the actual summit, which was very windy indeed, but bearable. That said, it was rather an anticlimax after the start to the day. I am not enamoured of scenery that is almost a monochromatic, dull blue, which is what you get when the sun has disappeared once more behind clouds. On the descent, there were streams and fungi and fabulous conglomerate boulders with ferns in abundance to keep us occupied as we walked the very well-graded track. Lunch at the Raspberry Farm was, as ever, delicious.

Sunrise next day was far better than one could ever have hoped for, especially given the thick clouds of the previous evening. We enjoyed the spectacle, and then breakfasted before heading for the actual summit, which was very windy indeed, but bearable. That said, it was rather an anticlimax after the start to the day. I am not enamoured of scenery that is almost a monochromatic, dull blue, which is what you get when the sun has disappeared once more behind clouds. On the descent, there were streams and fungi and fabulous conglomerate boulders with ferns in abundance to keep us occupied as we walked the very well-graded track. Lunch at the Raspberry Farm was, as ever, delicious.