The Leeaberra Track: a golden opportunity that’s somehow missed the mark

The idea of the Leeaberra Track is great: a pleasant walk along a low level range that runs parallel to the ocean (offering occasional glimpses of it), and which visits several beautiful waterfalls. It’s a fabulous alternative for times when the rest of the state is being drenched or burned, which was the situation this February, when Tasmania, having mostly been burned out and inaccessible, turned on massive storms with viciously spewing water. Douglas Apsley National Park looked clear of both fire and storm, and our group of four, sick of being soaked further west, retreated there for a more comfortable walk. (Photo: Bicheno the night before we began).

The idea of the Leeaberra Track is great: a pleasant walk along a low level range that runs parallel to the ocean (offering occasional glimpses of it), and which visits several beautiful waterfalls. It’s a fabulous alternative for times when the rest of the state is being drenched or burned, which was the situation this February, when Tasmania, having mostly been burned out and inaccessible, turned on massive storms with viciously spewing water. Douglas Apsley National Park looked clear of both fire and storm, and our group of four, sick of being soaked further west, retreated there for a more comfortable walk. (Photo: Bicheno the night before we began).

In your face cutting grass (Gahnia grands). We saw lots of this.

In your face cutting grass (Gahnia grands). We saw lots of this.

The Leeaberra Track’s first problem is the start, which is inaccessible for most tourists (unless they have rented a 4WD), or poses a logistical problem, as a car shuffle is needed at the end to retrieve the car abandoned at the start. The next problem is locating the minor dirt track you are supposed to drive along to get the said obscure start. With a carload of experienced people, we sailed past it the first time, as it is unsigned, bushed over, and looks like a track a farmer might use to deliver hay to his cattle. Hint: there is a pole with the number 063. That inauspicious piece of dirt is your road. It’s just past the first creek crossing south of Piccaninny Point. Only a few hundred metres in, you meet your first obstacle: a ditch that is sharp. On my own, I would never have driven across this ditch, even in my Subaru Forester. If you have a 2WD, forget it. Peter Grant’s excellent blog on this track reports that they parked here, and spent three and a half hours walking up to the start. He writes: “We arrived at Thompsons Marshes late in the afternoon, thirsty, sweaty and feeling as though we had already done our day’s work. Welcome to the start of the walk!” Elsewhere he calls it “cruelly, sweatily tedious”. (See url at end).

Snowberry (Gaulthiera hispid). We also saw plenty of this beauty.

Snowberry (Gaulthiera hispid). We also saw plenty of this beauty.

We were not in my car at this stage, so progressed on to the second, even more foreboding, ditch, where we parked the car rather than risk needing a tow – not available – to get out. We then walked 48 minutes along a dirt road to the start. (Just in case you don’t know me, I consider walking on dirt roads to be a totally different ‘sport’ to bushwalking. It provides little pleasure, and a merely functional role.)

Let the track begin. It was fine if you like dry sclerophyll forest. This was, for me, a means to an end, and the end was the waterfalls that lay ahead. I was also curious to know what this track was like, so I guess that ‘means’ was also being satisfied. We were walking in nature, and, hey, that’s much better than most alternatives. The rangers I met at the end told me with voices warm with affection that the area is truly beautiful in December when it is alive with wildflowers. I can imagine that must be a great sight.

Let the track begin. It was fine if you like dry sclerophyll forest. This was, for me, a means to an end, and the end was the waterfalls that lay ahead. I was also curious to know what this track was like, so I guess that ‘means’ was also being satisfied. We were walking in nature, and, hey, that’s much better than most alternatives. The rangers I met at the end told me with voices warm with affection that the area is truly beautiful in December when it is alive with wildflowers. I can imagine that must be a great sight.

Heritage Falls from above. Apologies about quality. Read text for reason.

Heritage Falls from above. Apologies about quality. Read text for reason.

One hour twenty after the “actual” start, we arrived at the first official camp of the walk, a clearing beside the Douglas River upstream from the Heritage and Leeaberra Falls, but one from which the river was not at all visible, as the cutting grass surrounded us on all sides, providing a thick green curtain, and a rather impenetrable barrier to the actual water, which I wanted to find so I could drink some, if nothing else. I felt closed in, claustrophobic. We ate, and then set out for the falls. The sign said “45 minutes return”. Joke. Laugh. I am not a slow mover, and I took 33 minutes to the TOP of the first falls. The base, and object of my quest, lay another six minutes beyond that. And then, of course, I also wanted to see Leeaberra Falls, further yet again. The route which once existed has been choked by flood debris and never cleared. Mostly, you can’t find where a route once was. The others made slow progress, and I began to be worried that I would be called back before I had seen my treasures, so dashed on to see and photograph before this happened. The others contented themselves with the top of Heritage, so I was right in my guessed need for haste. (Warning, do not use haste when descending to the base of Heritage Falls: it is almost vertical, and maybe half the rocks you might want to grab would come out at a touch. I descended with extreme care, testing everything before commitment was made.)

Heritage from the base. The edit is mine, but not the original shot.

Heritage from the base. The edit is mine, but not the original shot.

The falls were lovely, even in midday glare, and were flowing nicely. But horrors!!!! When I went to take my first shot, my camera announced that its battery was exhausted. How dare it be so weak. We’d only just begun. How unfit can one Sony battery be?? OK. No long exposures this trip. I hoped that with due rest between usages, with no LE or zooming, and with only one photo per falls, I may at least coax it to take a single shot of all five. I felt totally flat and devastated. I even considered running (tentless; packless) to the end to retrieve my trusty Canon from the boot of my car and running back again. Considering the thickness of later marshland, I’m glad I didn’t.

I got in a single 1/15th sec (erk) shot from the base, and then went along the rocks to the shapely Leeaberra Falls, whose twists and turns really appealed. Another 1/15 effort, oh the crime of it all. I will be back (and will replace these photos that have to do for now).

Leeaberra Falls. I loved the shape. I will be back.

Leeaberra Falls. I loved the shape. I will be back.

Not being anything like as exhausted as my lazy battery, I dashed back to the others at the top of Heritage, and went with them to collect our packs and proceed on, up the slope to Lookout Hill (640 ms asl), where we dumped our packs in the saddle (not much below the ‘summit’) and went to look out. The view was not to die for, but was a bit of variety from dry forest and cutting grass.

From there began the whopping and seemingly interminable drop to the Douglas River Campsite, number two on the list of possibilities along this track. Now, this one was a gem. I loved it. It was open, with views of Black Boys / Grass Trees ‘Xanthorrhoea australis’ to the river. The river itself had fabulously weathered rocks, which made kind of tiny islands you could perch on and sit in the middle of the river with water flowing past on all sides. It was cooling and restful. Later, as the sun entered its golden hour, a tunnel of aureate light drew our eyes upstream. Unfortunately, the mozzy population had not had visitors for a long time, and each mozz was starving. They found in me an excellent meal. Pity about my delusions of being too skinny to be tasty. Anyway, with bellies a bit satisfied, they were calmer the next night.

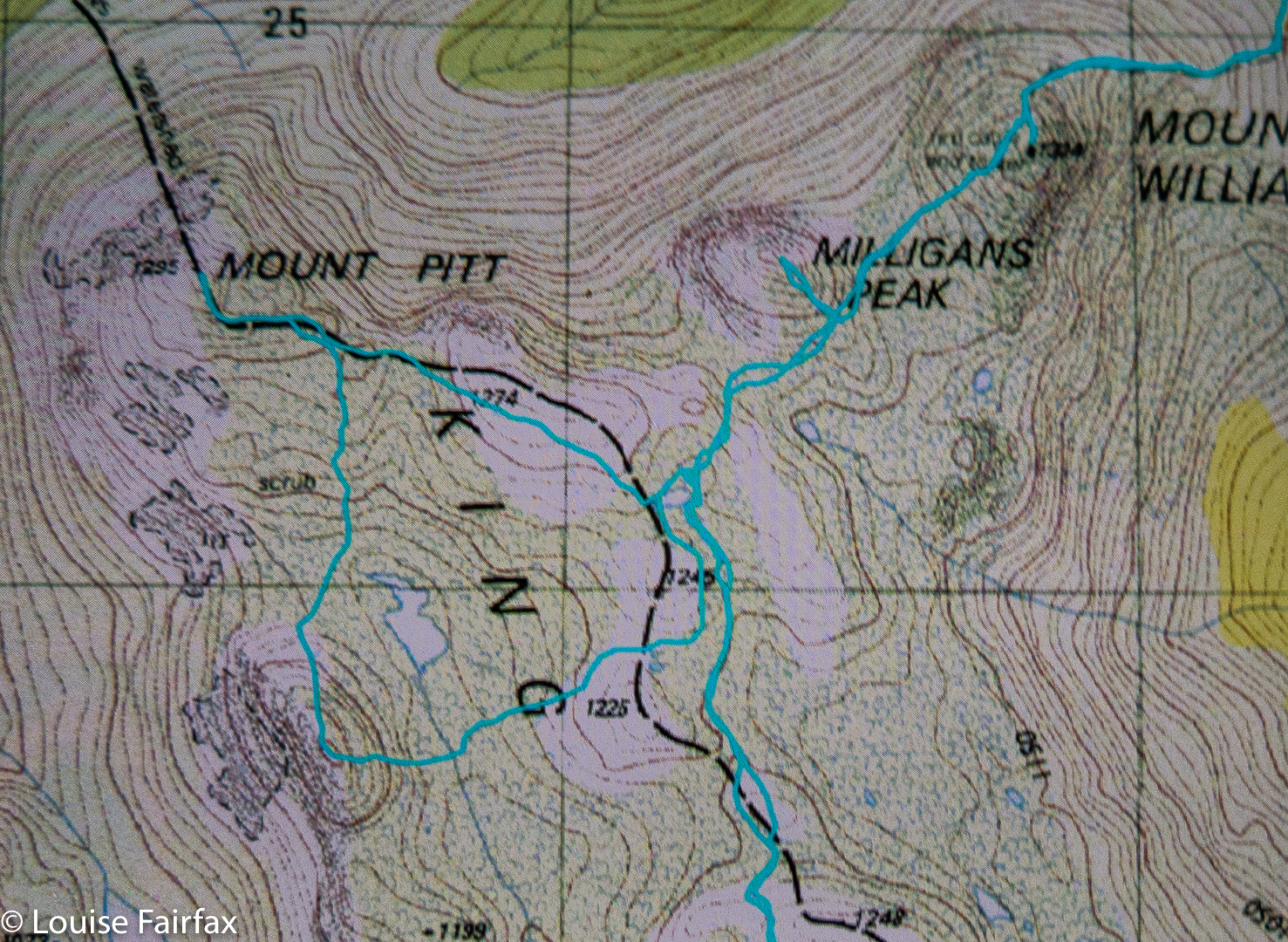

A blue line on the map indicating a waterfall. Upstream of the Douglas R crossing; bend in the river. I have imaginatively called it “Falls 1”.

A blue line on the map indicating a waterfall. Upstream of the Douglas R crossing; bend in the river. I have imaginatively called it “Falls 1”.

On Day 2, we did not move camp, as we had “serious business” in this area. One of our number wanted to climb Mt Allen, so off all four of us set, up the very pleasant open forest leading to a higher saddle (a climb from 90 ms to 450 ms asl). At this saddle, the Leeaberra Track meets an emergency exit road heading down the coast. We walked along this uninteresting stretch of territory for 4 kms, until at last we were at the foot of Mt Allen, and could do the far more enjoyable 450 (horizontal) ms across bald patches of rock and through light scrub to its top (50 ms “climb”). I really can’t call that black dot a summit. It was merely the highest point on a pimply lump, and offered no views. We then had 450 ms of bush and a repeat 4 kms along the road back to the saddle. I had had enough of viewless, pointless pimples, I decided. I would not submit to the afternoon’s offering, as that would mean I would never get to see what I had come for: the waterfalls along the Douglas River in this stretch. Now, here was real beauty!! And I am a beauty hunter, not a list ticker. I returned to camp, ate lunch, and then set out on my quest.

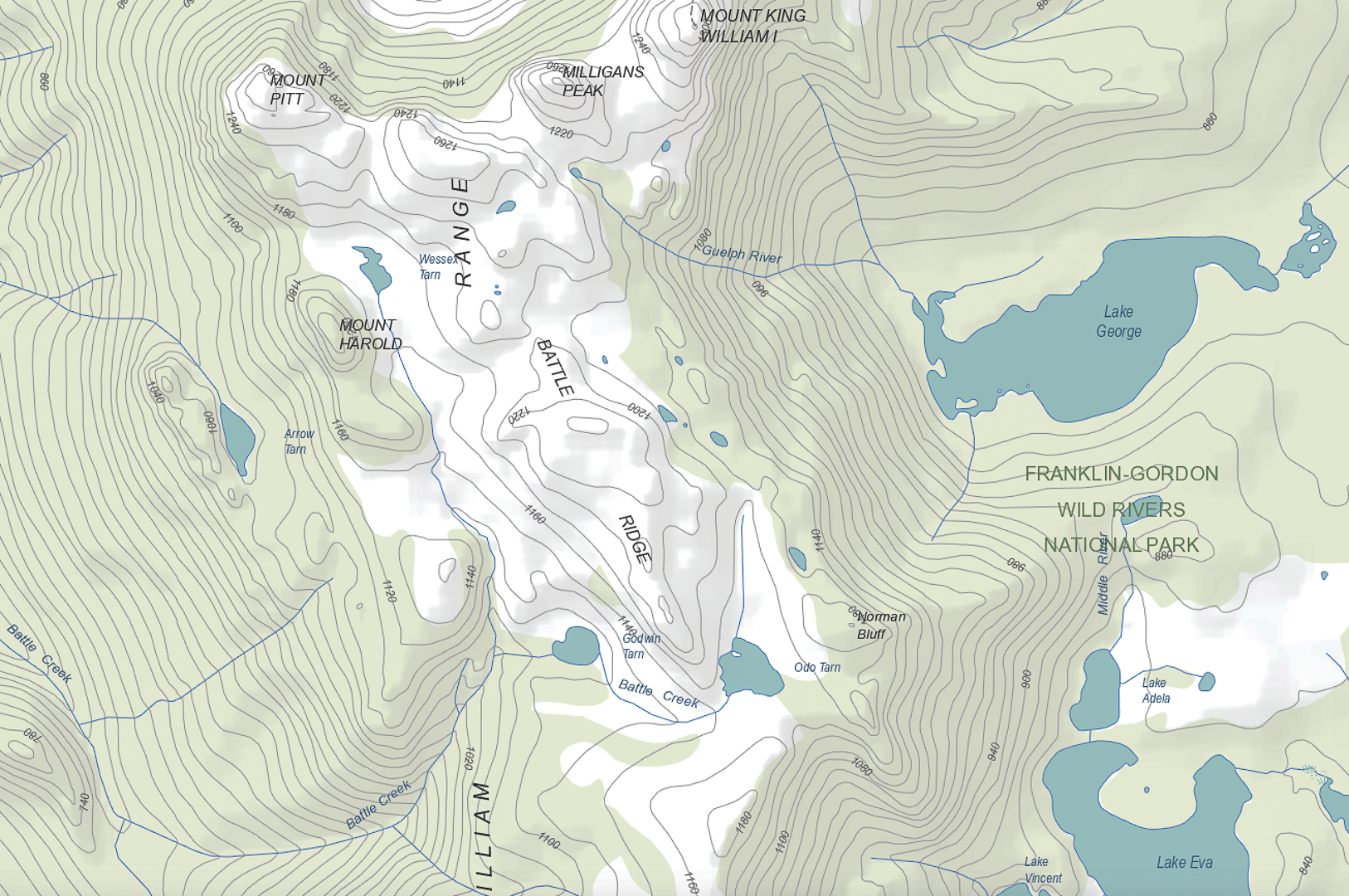

You can see the purple line where we crossed the river and camped to the east of the photo. Then, if you follow the river upstream to the NW, you will see Falls 1 on a bend and Falls 2 further east of that. Dark green is rainforest.

I had the afternoon to myself: just me and a gurgling river and scenes of magical beauty. I decided the northern bank of the river offered the best chance of reaching the falls, so crossed at the campsite and then rockhopped for as long as possible upstream. For seven minutes, the hopping was great fun, but I then encountered the first of many obstacles: a cliffy bluff with steepish sides falling directly into rather deep water. The forest above was thick with needly bushes. I decided to grab roots and ease my way around the rock, swinging like Jane of the jungle – and having great fun while I was at it. The penalties for falling were not too great: I would wet my clothes and boots, and no doubt damage my electronic gear, but I would not, personally, suffer any great damage (other than to my pride). I took the risk and concentrated hard.

After maybe twenty minutes of this, I noted that the mapped rainforest above the bank had now materialised. I could thus abandon this swinging sport, and use the clearer, more pleasant forest to climb above any remaining bluffs. Fifty four minutes from camp, I arrived at “Falls 1”, situated on a bend of the river. This was a wonderful gurgling, frothy mass of pools and waterholes, of action and beauty. I managed to coax my camera into another wretched dash of a photo before proceeding upstream to “Falls 2”, which I could actually see from the first ones, but, in order to get a better view, had to do another stint of climbing. I am all eagerness to return to these two falls with a camera that works (and a tripod, CPL and other filters).

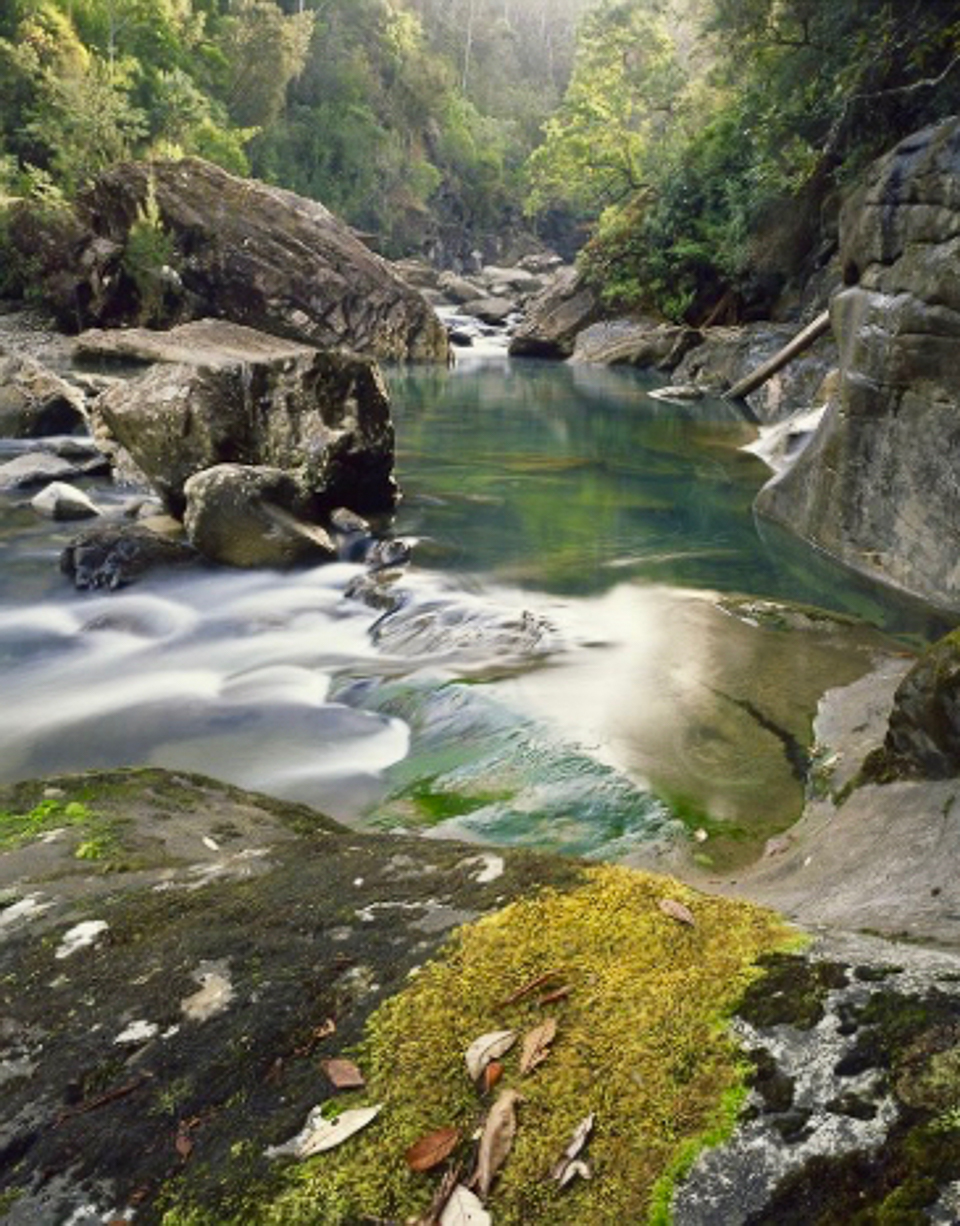

Douglas River as Dombrovskis saw it. Isn’t this inspiring! It’s part of the reason I was so upset at my camera situation. This is here to remind myself of why I’m returning (and because I love good photography, and don’t like publishing less than that).

Douglas River as Dombrovskis saw it. Isn’t this inspiring! It’s part of the reason I was so upset at my camera situation. This is here to remind myself of why I’m returning (and because I love good photography, and don’t like publishing less than that).

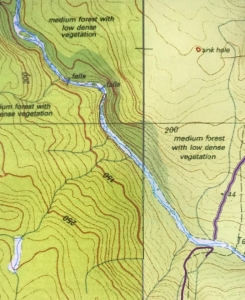

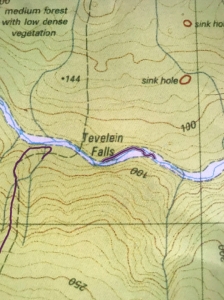

Back at camp, there was no sign of the others, so I set out for Tevelein Falls, supposedly a few hundred metres downstream. I went to where they were supposed to be on the map, but the cupboard was bare. There was a very nice gorge, and some sweet cascades, but not a waterfall. I thus continued for another five hundred metres, and found what is in the photo below – pretty nice, but not really a waterfall. Yes, the camera gave one final, choking and reluctant click (had I actually scored an image???) before signalling its desire for an urgent sleep.

There was nothing where the map said the Tevelein Falls should be. This is maybe 500 ms downstream of that. (See map directly below).

There was nothing where the map said the Tevelein Falls should be. This is maybe 500 ms downstream of that. (See map directly below).

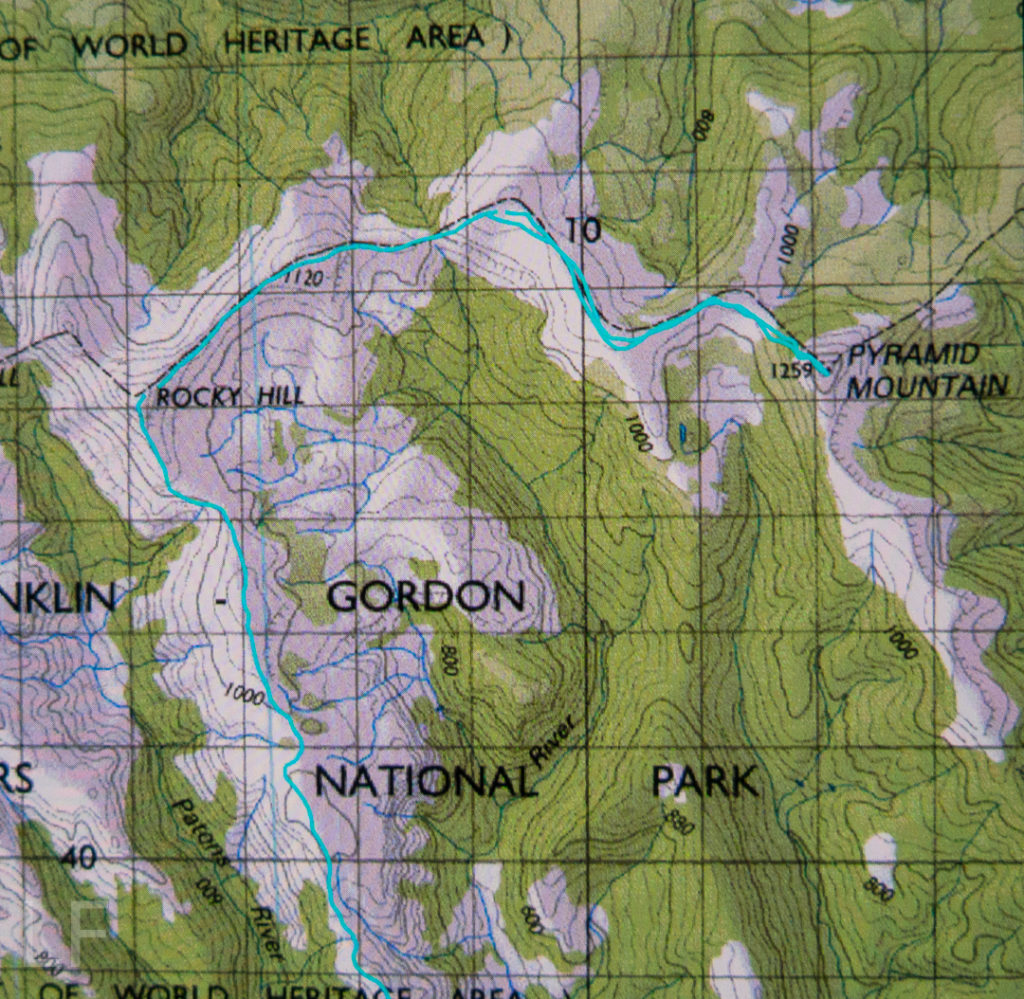

I only plotted the part where Tevelein Falls should have been and the extension I did beyond that, looking for it, mismapped. I had come from our camp, purple line to the west of the supposed falls.

I only plotted the part where Tevelein Falls should have been and the extension I did beyond that, looking for it, mismapped. I had come from our camp, purple line to the west of the supposed falls.

I returned to camp. It was 4.50. The others hadn’t returned, but I was starving. I cooked and ate in the river, and the others returned and joined me. It was beautiful there, watching the fading light and chewing cud.

Taken with a borrowed camera. Thanks Karin. Dinner on Douglas River.

Taken with a borrowed camera. Thanks Karin. Dinner on Douglas River.

On Day 3, the schedule was to climb more viewless pimples, and camp at the Douglas Marshes. Given the mozzy population, and the most inauspicious name, I had a deep sense of foreboding which was not ameliorated in the slightest by the reality we encountered. And I was quite over pimple picking.

We arrived in the stagnant, soggy area. Bzz, bzzz. The water did not seem drinkable. The air was foetid. No breeze could read a map to find its way here. The marsh vegetation (cutting grass, melaleucas) was way above my head, so there was no visibility.

“How far to this one?” Maybe a very small number could persuade me to stay. “Six kms return”, came the answer. Na, sorry. Zu viel verlangt.

Two said they’d stay and wait the expected six hours for P to return. I said I would finish this trip off, and come back to collect them next morning to do the car shuffle. This track was not exciting me now there was no more beauty.

Off I set, shoving my way through thick, resisting and cutting marshland, a trackless waste of unappealing scrub. If there had once been a track, there was no longer one now. I navigated my way through the green jungle to the spur beyond on compass (the spur ahead was not visible to me). Even once on higher ground, the track was only intermittently visible. No matter; I can navigate. Every now and then I picked it up along my route, but it wasn’t worth searching for. Just going my own route was quicker. I did dump my pack to climb Mt Andrew, just because it was there and not too far off the track, even though it, too, was little more than a pimple. It provided a break for my shoulders.

At last I found myself finishing. I felt like yelling “Hoorah”. There, I found two rather sheepish-looking rangers, who tentatively asked me how I’d found it. I won’t tell you my answer in case you think I’m a polite and nicely spoken person. I smiled as I told them the truth, and they laughed at my answer, admitting that it was “rather overgrown”, and that they hadn’t had a chance to go in last winter and clear things up at all. It’s not their fault. Perhaps if the government funded tracks that already exist instead of searching for new ways to desecrate the bush, the situation might be a lot better.

At last I found myself finishing. I felt like yelling “Hoorah”. There, I found two rather sheepish-looking rangers, who tentatively asked me how I’d found it. I won’t tell you my answer in case you think I’m a polite and nicely spoken person. I smiled as I told them the truth, and they laughed at my answer, admitting that it was “rather overgrown”, and that they hadn’t had a chance to go in last winter and clear things up at all. It’s not their fault. Perhaps if the government funded tracks that already exist instead of searching for new ways to desecrate the bush, the situation might be a lot better.

Conversation finished, I hurried to Bicheno for a delicious cafe lunch to cheer myself up. I was so hungry that I also went to the bakery mid afternoon for coffee and cake, and then paced beaches and read until I could go to the fish restaurant for the best seared tuna steak ever for dinner. And then, at last it was time for a beautiful Bicheno sunset, real photography, and, following that, hobnobbing with nice tourists who were waiting for penguins.

Next morning, our group was reunited for the completion of the car shuffle. With coaching and encouragement, this nervous driver made it across ditch 1, and even all the way up to P’s Jeep. Mission completed. Next time, I will leave by that boring exit road rather than face those marshes again. Besides, the finish area has no transport possibilities if you don’t have a second vehicle waiting for you. Whatever you do, your original car is miles away, hidden in forest en route to the start. I don’t believe a taxi would take you past ditch 1. I would love to tell you a different story about this track, full of possibilities, but, alas, I can’t. Not yet.

Some stats: Day 1, “Ditch 2 to Douglas River crossing”: 17 kms + 745 ms climb yields 24.5 km equivalents

Day 3 “Douglas Crossing to the end”: 15 kms + 690 ms climb yields 22 km equivalents.

Total (including the extra to get to the start): 32 kms with 1435 ms climb yields 46.4 km equivalents.

The URL for Peter’s blog is (and note its name): www.naturescribe.com/2011/10/good-walk-spoiled.html

I have not put in the whole long gpx route of what we did, as it covers 4 more maps. If you want the gpx, please let me know and I can email it to you.