Some of my followers on IG and blog have asked if I could give advice on packing – of clothes and food. I am happy to oblige, and will begin with gear. Before I do so, however, I need to stress a couple of matters that seem important to me, and that should be borne in mind when reading this.

(1) Individuals differ from each other in the extent to which they feel the cold. What is good and necessary for me might be insufficient for you. In the case of ‘the cold’ that is actually unlikely, as I am a renowned wuss, but thought I’d better mention it.

The most important thing is to know your own body, and know it well before you step into the wilderness. Being in the wilderness is as much an experience of self learning as it is one of seeing beautiful wild places.

(2) Begin simple, so you can learn from your mistakes without killing yourself. I have heard of first-timers who want to start their ‘bushwalking career’ with the Mt Anne circuit or the Western Arthurs. This is like a beginner in high jumps setting the opening bar at 2 metres.

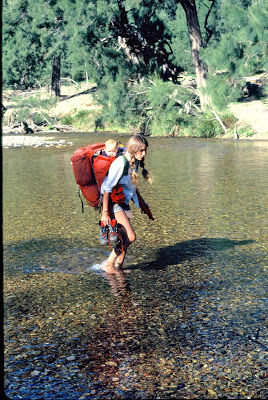

When we wanted to take our 6- and 8-year-old daughters on the Overland Trail, we first took them on the 33 km Freycinet Peninsula walk as a warm-up – both for them and for me, the provider. I weighed and measured everything in those three days to learn for double that number.

If you have never experienced even a daywalk on a Tasmanian exposed mountain in a black mood, how can you plan for five? I once took a Swiss friend to Cradle, insisting he pack certain precautionary clothes. He was indignant, and scoffed: “I live higher than the summit of this mountain, and you’re telling me what to bring?” He didn’t get past Hansons Peak, and had the grace to apologise. The incident points to the fact that height is not felt in the same way in all circumstances, and height on top is very different from the same height in a valley.

(3) You need to be prepared to be tough and uncomfortable if you don’t want to burden yourself with a pack full of wet gear. Most (all?) of us put on wet clothes each day (in continually raining conditions) rather than wet a different outfit each day, only to have the new outfit wet after five minutes. This means, of course, that your daytime get-them-wet clothes need to be made of a fabric that is comfortable and warm when wet, and that will dry quickly if given quarter of a chance. I use icebreaker gear next to my skin, supplement it with a thermal or icebreaker long sleeve top, then have a third layer of a padded jacket that is warm when wet (mine is a macpac Pulsar hoody, not down for day), and over that, my Anorak (rain jacket). Even so, I need to keep moving to keep warm. PS Now I use an Arc’terx hoody instead of a macpac Pulsar, as it’s warmer.

(4) You must have a complete dry set of everything for nighttime, when it is imperative that you warm up and sleep dry. This includes nighttime woollen socks, gloves, beanie and undies; i.e., double up on everything. (In summer, you can sometimes get away with one thermal top and long johns – but even then, you can get caught out, as I have been; better to be safe).

(5) Have a bag of warm, dry clothes in the car. Assume you’ll arrive back cold and wet. Anything else is a bonus.

My Gear List.

Tent Sleeping bag

compass map

Plaster can mend trousers as well as legs.

You have no idea how handy doubling up can be. On a ten-day expedition I went on:

I forgot toilet paper, but W had 2 rolls and gave me one;

M forgot his hat, but J had two;

B lost his sunglasses, but J had two pairs;

S broke his stove, but A had two;

C broke her spoon, but I had two;

Someone tore their pants, but C had a sewing kit;

W broke his pole, but S had a pole repair kit;

My tablets for pain were dated 2007, which A informed me would not work in 2016, but she had spare.

The list goes on, for sure. This is all I can remember.

Helping out and being helped in mutual working towards the goals is the theme.