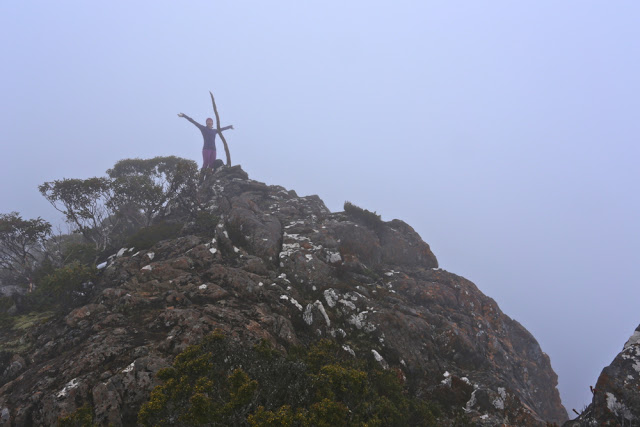

Mt Hobhouse success.

The forest just below the rocks of the ridge. Our first stop where we took off the packs (for a quick drink) – which meant I could have an equally quick snap with the camera that was tucked out of the weather in cosier environs.

The forest just below the rocks of the ridge. Our first stop where we took off the packs (for a quick drink) – which meant I could have an equally quick snap with the camera that was tucked out of the weather in cosier environs.

“Mt Hobhouse. That’ll be a tough one to get on a short winter’s day,” an acquaintance said, and of course, he was right, but we just wanted to do it, so that was that. Did one always need to be sensible?

I was farewelled on my way by the Launceston debating community, as we had had Parliamentary Shield on the Saturday. To many of those people, who inhabit a very different world to mine, the notion of abandoning creature comforts to drive over an icy and dangerous Central Plateau to then attempt to climb a remote mountain in semi-snow was something almost outrageous. They wished me well with all their wonderful hearts. My students had won both trophies on offer. The memory of their warm hugs and delighted faces, and the joy shown by their families, lining up to photograph them with their booty, buoyed me as I drove. I don’t often travel to the mountains in a skirt and stockings. I hoped Angela would recognise me in this uncharacteristic and utterly unsuitable attire. She laughed when she saw me and suggested I carry the stuff up to wear on the summit for our victory photo. I declined. We were going to stay at Bronte Park Village which has an open fire. I’d dress more appropriately later. Let’s brave the ice on the road now, without delay, before it got any worse.

…

And here we were, sniffing the top. It had to be that next lumpy shadow appearing out of the mist. I’d checked off all the features as they went by; this was finally it.

“I can hear in your voice you’re getting excited now,” Angela commented, with enough momentum to carry her to the top even if her legs dropped off her torso right at this moment.

“Yep,” I agreed, unwilling to call it success until this moment, but now, now, it would take an atomic bomb or a fatal heart attack to keep us from that prized summit stick. We crunched on the last of the snow and covered the final twenty metres of our day’s directed endeavours.

The mountain had seemed so formidable on our first attempt – because we had come up onto the ridgeline a tad too early and had met a solid wall of cliff, well fortified by a palisade of dauntingly thick scrub. Now it seemed nothing but a song and dance across the ridgeline to the top. Amazing what 100 ms difference can make.

This trip was not about views. It was about undoing a bad job last time and not admitting defeat. Last time we had done all the hard work of getting up onto the same ridgeline we were now on, but we had been timed out of finding a way around the cliffs so we could reach a point from which ascent was possible. We had started too late, underestimated our mountain, and were not prepared enough in our homework (we had actually not intended to climb the mountain on that day. It was a last minute switch).

So dedicated were we to our task this time that the only breaks were a toilet stop, a quick drink before the ridgeline, and a bit of time wasted looking for a cairn that we have decided has been knocked down by fallen timber (of which there is a lot. Recent storms have caused quite a number of new obstacles, even since last time we were there). We were at the top by midday, having survived the overgrown and very unclear bombardier track, the magnificent and quite open rainforest of the early part of our ridge, the slow and snowy bauera and eucalyptus band between it and the ridgeline, and the final, enjoyable semi-romp of the last section where the bushes were lower and a pad could even be seen.

The weather was such that we didn’t linger long on the summit, and chose to eat our rather hasty lunch in the rain at the bottom of the cliffs prior to plummeting down into the bauera once more. I timed it to this spot. Twenty-three minutes. It was where we had passed through on our retreat last time. How sad that we had been so close the summit, yet had not had the time to go there. Of course, at the time we didn’t realise the journey would be so quick, and our decision to turn around had been a wise one given the time. We did not have forty six minutes (plus photos) to spare on that day, and we thought it would all take a lot longer than that, containing the possibility, we thought, for many errors and false chutes. This time we knew better, thanks to the kind advice offered to us by both Phil Dawson and Becca Lunnon, who each described their (basically identical) route across the ridge. That knowledge gave us more confidence this time.

The trip back, retracing our steps was uneventful if you don’t count the fact that our clothes were so sodden they were hard to keep on, and that we increasingly resembled odd wooden puppets trying to move in a way that kept pants up and frozen feet operating. We were both a little worried about how very numb our fingers were, knowing that we would need them for our lives right at the very end, but, here I am, alive to tell the tale. The return trip was slower than the ascent – partly due to the fact that the bushes now bent low over the bombardier “track”, making it impossible to differentiate from its ambient non-track scrub. We lost it several times, but were still out with a nice amount of light to spare so we could see the ice and snow on the road and attempt to dodge the animals that decided suicide at Angela’s hands was the way to go.

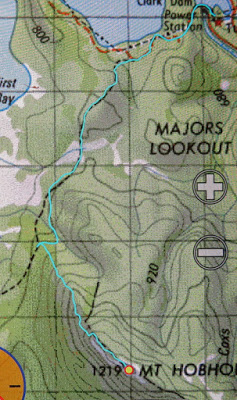

Here is the 1:25,000 version which usually gives you more information, but with the contour lines so very washed out, is not as useful as it should be. A combination of the two should give you all the information you need to determine our route, I hope. The line crossing the ridge is a boundary line. Don’t be tricked into thinking it’s a helpful track, although at the very top, just for the end game, there is a bit of a pad in the shorter vegetation.