Mt Bobs and the Boomerang. Neither, and in two days.

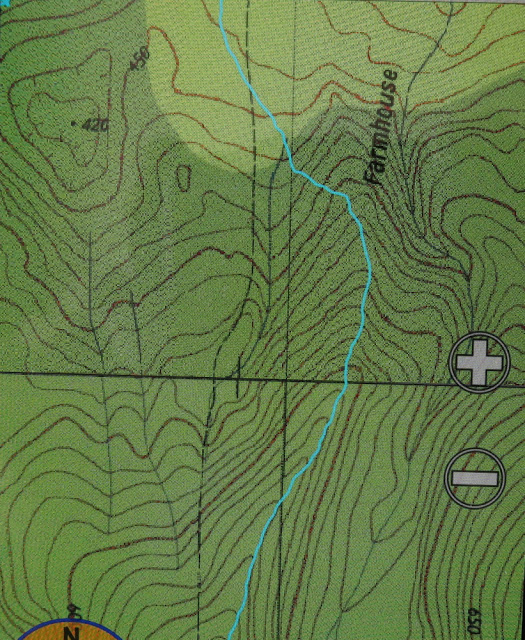

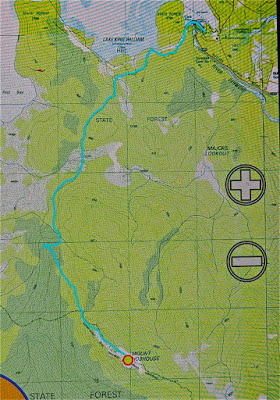

Farmhouse Creek, the famous.

Farmhouse Creek, the famous.

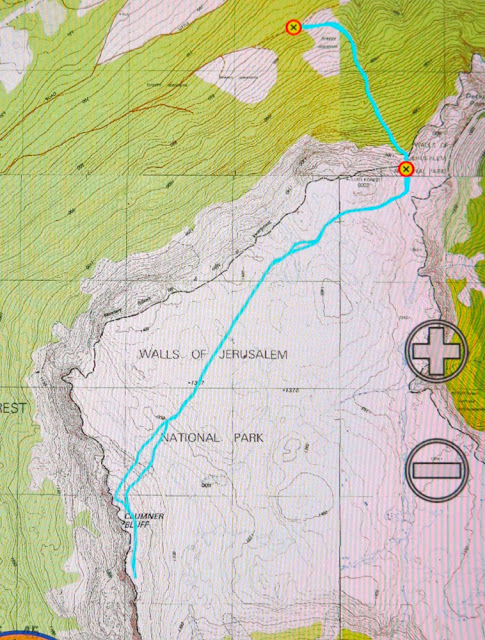

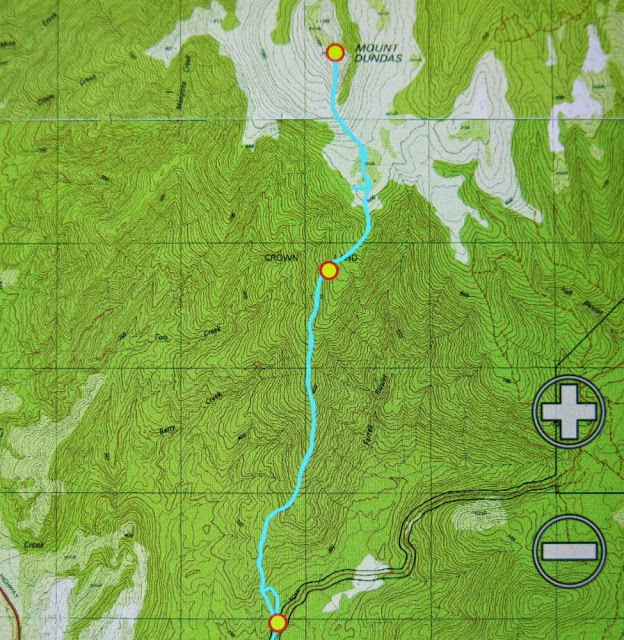

“BOBS?? THIS weekend?” queried our amazed and knowledgeable friends when my husband explained my absence from the gym. They knew the full implications of an immediately post-winter attempt on Bobs, especially having just returned from sludging their way around their own, lower and less southerly mountain, where they had found the going slow and hard. They were right. Bobs was pretty bad – and they had retreated from their mountain before the rains began.Day one was not a booming success. Unfortunately Friday morning was the earliest I could get away, which was one day too late for the window of opportunity that gave three dry days for Bobs. And it certainly didn’t help that, with one thing and another, we didn’t leave the carpark at Farmhouse Creek until 10.45. If these suggest to you a lack of respect for the worthy Bobs, you are probably right. We have learned due respect now. Perhaps we also needed more deference for the amount of water that must have accumulated after the kind of snow dumps we’ve had these last few months. However, my climbing partner has personal reasons for trying to collect as many Abels as he can before Christmas, and we both enjoy giving things a go, so there we were. Our third accomplice in mischief would have also given it a try had she not been required to be at work on Saturday. She was at home consoling herself with wine. Perhaps this was not a bad idea.

It was very exciting for me to see the famous Farmhouse Creek up close. A frisson of delight coursed through me just thinking of the many connotations this stream holds in its compass. The pad to the right, immediately after crossing the bridge, was clear enough most of the time. We were delighted to be underway and chatted furiously, making up for several months of not seeing each other, exchanging news and stories, enjoying the pellucid, whisky-coloured gurgling mass beside us and the almost lurid green forest as we made our way to the crossing of this now mighty river – swollen as it was – before we began our actual climb. Apparently one rises about 250 ms in this section, but it is not noticeable.

It’s quite a long way; I had had breakfast at 4.50 a.m.. On the dot of 12 I begged for lunch, and Mark was cool with that. There was a nice stream flowing, but I was told it was not Farmhouse creek, even though it seemed pretty big. There were quite a few mud puddles, which increased in number and size as we went along, but – and now I can speak in hindsight – the going was pretty good in this section: just a few fallen logs and trees to climb or attempt to skirt; what you’d expect on a longstanding, unmaintained track.

The real fun began at the mud plain called by some “track junction”. Now, to have a track junction, you actually need at least two tracks, so I question this terminology. We did see a stick with two tapes on it, but we assumed it was just to announce “You are still on the track”. We did make explorations off to the left to make sure, but the slight suggestion of a pad was really too minor to be promoted to this status; the stick with tape was a stick and not a tree as the Abels book said, and we hadn’t been going long enough. This was a wily false pad. We were not fooled. On we went, chatting merrily. However, after some time (and the gps says about 700ms) we were climbing more contours than seemed reasonable amongst friends, so we did the gps the courtesy of a check (I had been trying to save battery by not overusing the screen). Alas it confirmed that the stick must have been the junction. My watch said this was not good news with respect to our broader hopes for the day. Back we went. When I visited the stick the second time and looked up high in the air, I saw that giants had indeed put more tapes there than either of us had noticed, focussed as we were on how deep our feet were sinking and other suchlike matters. The tapes were well above my eye level. We put a bright pink one just above where my eyes look for good measure, one that people like us could see.

There’s a creek crossing a bit on from there, so we stopped for a quick drink and to refill our bottles, and on we went, worried now about the time. The book Mark had said 3 – 3.5 hours to the campsite from here. It was exactly 3.5 hours until dark. Pitch dark, that is. Unfortunately, due to problems locating the vague thing glorified by the term “pad” in forest thick with newly fallen trees, branches and leaves following a winter that has been rather active in weather events, we spent more time in a game of ‘Pooh finds hephalumps’ than in making forward progress. There were also many mud ponds of unknown depth that we tried to evade down lower that prevented us breaking the world record on this occasion. Unless people document startling PWs.

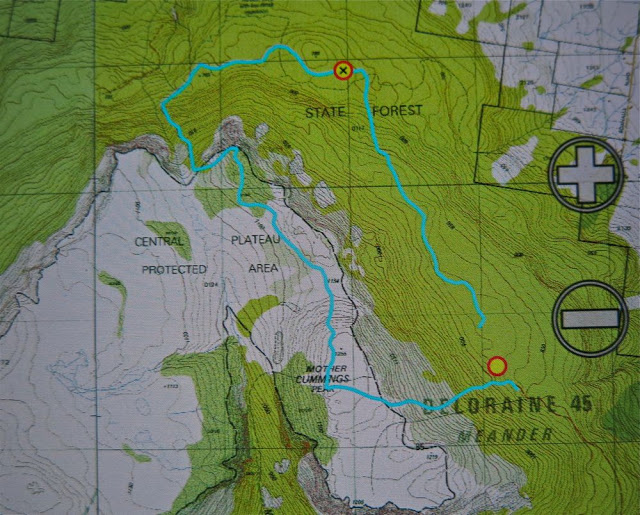

Darkness – of the proper, pitch variety – set in as we were descending to what Chapman describes as a button grass valley. We found no button grass by dark or by day. Just more thick forest and deep, deep mud. When it’s very dark, sinking in deep mud is not a nice thought. Our pace slowed even further. The compass was now needed as the land gave us no clues. We were supposed to be in a valley heading SW. We could find SW on the compass, but no particular valley on the ground. Nothing that yelled: “I am a valley. Just stick to the lowest point and follow me up.” The pad, being now full of mud, was shinier than the non-pad, so we made a little cautious progress, but once we reentered the forest, the shine lost its sparkle and we were back playing Pooh and hephalumps again, circling tapes to try to find where the pad went from that point and making footprints to later get excited about. Simply heading SW was an even slower option in forest that tangled, so we only resorted to it when desperate (which we became at about 8.30).

We never did get to see the sinkhole, but we did see where one would lie were it not drowned. We retreated and found two tolerable spots for tents. It was now 8.45. As I was boiling water for dinner, Mark yelled out: “Hey Louise, I just found a tape in the tree above my tent. We’re on the track.” The rain began soon after that. I enjoyed listening to it beating on the tent as I very easily drifted into sleep.

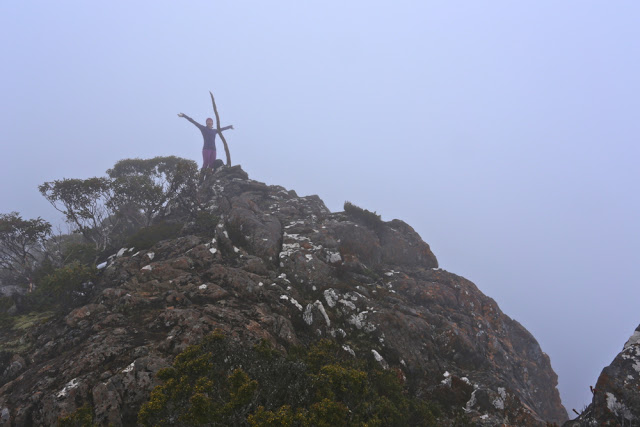

“Wake up, Louise.” The rude sound penetrated my dreams. But we had agreed on a 6 a.m. start. Outside, Mark was standing in the rain, offering me three alternatives: climb, wait a bit, or bail out.

“Bail out?” I almost yelled (well, actually, I think the volume was “yell”) in shock.

“Yes, the book says it’s four hours to the summit from here. That’s eight hours in the rain and mist with no view and hypothermic conditions.”

“And no line of sight on the helpful cliffs,” I chipped in. With each passing moment, this “bail out” notion was seeming like a fantastic idea. What an ingenious guy Mark is. Within two seconds I’d agreed to it.

“Can we sleep in ’til 7?” I asked hopefully. Affirmative. Life is good.

I rolled over to listen to the rain and just enjoy the state of being in a forest this wondrous with its trunks heavily laden in deep spongy layers of the best green. The scene out my vestibule was a wonderfully Tolkienish vista. (Alas, it was too dark and wet to photograph).

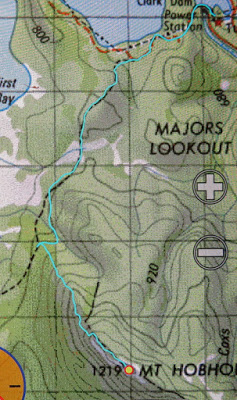

We had thought the trip back would be way faster than the trip in, with the wonders of vision added to the mix, and it was certainly quicker than our way there, but lighting-fast does not describe our speed. The amount of water that had fallen in a single night was truly astonishing. The mud puddles were now mud tarns. Divergences were extravagant to avoid a soaking. Why not just go through and get wet and be done with it? Because the depth of these puddles is unknown, and falling in up to your throat or high chest is actually a frightening experience. It requires great strength to get out again, and is rather cold and dirty to boot. Besides, I had my camera to protect, and my brand new (expensive) Anorak. I pussyfooted around cutting grass and scoparia in an attempt to have it last more than a single expedition.

Our lunch was had in the campsite just before the intersection – a nice clear place to put down the packs. It was a nice clear place for snakes, too. I have never before seen two snakes curled up together. I wanted to poke one with a stick, just to see what would happen, but decided against it. We both did go quite close, however, curious about this daring pair who appeared long before snake season was due to start. (The rain had now stopped). They seemed a little curious about us, too. We parted on good terms.

All up, we carried our packs for 16 hours, which includes all the errors – circling, prancing around puddles, swinging from trees, having several attempts at sliding up logs that were as high as my eyes but offered no way around or under, and other suchlike games. The time does not include eating or photos – the only time we gave our shoulders a break. We had three rests going up, two coming back – just long enough to throw a quick bit of food down and some water, and we were away again. We got to the car, dreaming of hamburgers or better, only to look at the watch and know that even Banjos would be closed by the time we got there. It was quarter to five. No hope.

32.5 kms. 800 ms climb (which does not include any of the climbing on the way back, or the climbing we did in error. Real climbing is more likely to be 1100ms).I was very tired driving home. Ironically, I kept awake by blasting out (and singing along with) Bellini’s opera, La Sonnambula (The Sleepwalker).