Mt Ossa Dec 2017.

I was mesmerised by my visit to Mt Ossa back in December 2013, when I took a Swedish friend up there to sleep on the summit. What astonished me, amongst other things, was the beauty of the flowers along the way. (I was also captivated by the brilliant views, of course.) I hadn’t realised December was such a magic month in that area, and vowed I’d return with a better camera and a tripod for mach 2 some day. Unfortunately, it’s taken four years to find the opportunity.

I was mesmerised by my visit to Mt Ossa back in December 2013, when I took a Swedish friend up there to sleep on the summit. What astonished me, amongst other things, was the beauty of the flowers along the way. (I was also captivated by the brilliant views, of course.) I hadn’t realised December was such a magic month in that area, and vowed I’d return with a better camera and a tripod for mach 2 some day. Unfortunately, it’s taken four years to find the opportunity.

This time, there was to be no Elin, and, worse, no Bruce. Off I set anyway, not sure how things would be. I can’t predict my moods these days.

This time, there was to be no Elin, and, worse, no Bruce. Off I set anyway, not sure how things would be. I can’t predict my moods these days.

The first part went pretty well, and I was in at Pelion Hut in under three hours, despite my heavy camera gear, and definitely ready for lunch. I hadn’t got away from the carpark until 10 o’clock, so it was not an early lunch. Light drizzle had meant that stops along the way were not really wanted, so I was in need of a good rest as well as a decent feed. I ate my salad roll with gusto. Drizzle changed to steady rain. The world turned dark grey. My spirits are not buoyant enough to deal with that at present. I decided I should turn around and go home, and count this as a good training exercise. I didn’t want anything in this weather other than sulking chez moi with my dog.

The first part went pretty well, and I was in at Pelion Hut in under three hours, despite my heavy camera gear, and definitely ready for lunch. I hadn’t got away from the carpark until 10 o’clock, so it was not an early lunch. Light drizzle had meant that stops along the way were not really wanted, so I was in need of a good rest as well as a decent feed. I ate my salad roll with gusto. Drizzle changed to steady rain. The world turned dark grey. My spirits are not buoyant enough to deal with that at present. I decided I should turn around and go home, and count this as a good training exercise. I didn’t want anything in this weather other than sulking chez moi with my dog.

I set out for home, but then decided that was silly. Set out for the pass and decided I really didn’t want that either. Such vacillation. To and fro I went with each change off mind, trying to imitate a laden yoyo. In the end, I decided that I should start climbing Pelion Gap, to stop looking so stupid, and to try to warm up with the height gain before I made any big decisions (I was by now freezing with all that sitting around). Once I was underway, I talked myself into believing that I should at least go as far as the pass, even if not the summit, and maybe tomorrow would be more inspiring than today.

I set out for home, but then decided that was silly. Set out for the pass and decided I really didn’t want that either. Such vacillation. To and fro I went with each change off mind, trying to imitate a laden yoyo. In the end, I decided that I should start climbing Pelion Gap, to stop looking so stupid, and to try to warm up with the height gain before I made any big decisions (I was by now freezing with all that sitting around). Once I was underway, I talked myself into believing that I should at least go as far as the pass, even if not the summit, and maybe tomorrow would be more inspiring than today.

I slowed down the pace and ambled up the slope, enjoying the mossy banks beside the little creeklets, flowing happily no doubt due to the rain. The lush forest was pleasant in the misty conditions. Right near the top, just before one bursts out into the more open area, I had the pleasure of encountering a group of six LWC (Launceston Walking Club) members who had camped the previous night at the hut, and had that day climbed Ossa in the mist. In answer to my query about flowers, they reported that if I went high enough, I would find some (I had been deeply disappointed by the lack of them lower down – part of my general despondence). It was lovely to see people I know and to get warm hugs – and inspiriting to be told the flowers I wanted were to be found after all.

I slowed down the pace and ambled up the slope, enjoying the mossy banks beside the little creeklets, flowing happily no doubt due to the rain. The lush forest was pleasant in the misty conditions. Right near the top, just before one bursts out into the more open area, I had the pleasure of encountering a group of six LWC (Launceston Walking Club) members who had camped the previous night at the hut, and had that day climbed Ossa in the mist. In answer to my query about flowers, they reported that if I went high enough, I would find some (I had been deeply disappointed by the lack of them lower down – part of my general despondence). It was lovely to see people I know and to get warm hugs – and inspiriting to be told the flowers I wanted were to be found after all.

I didn’t stop at the gap, but kept climbing through the drizzle, in search of flowers. I found, I saw, I photographed. A strong wind joined the rain, and it was far from pleasant – and my socks and shoes were pretty sodden – but I was completely happy once I saw the colours of the scoparia flowers I had come for. I managed to find a sheltered spot for my tent – not easy when you’re so high with wind gusting from every direction, or so it seemed – and, in between photographing flowers and sunset, cooked and ate dinner in the protection of my tent.

I didn’t stop at the gap, but kept climbing through the drizzle, in search of flowers. I found, I saw, I photographed. A strong wind joined the rain, and it was far from pleasant – and my socks and shoes were pretty sodden – but I was completely happy once I saw the colours of the scoparia flowers I had come for. I managed to find a sheltered spot for my tent – not easy when you’re so high with wind gusting from every direction, or so it seemed – and, in between photographing flowers and sunset, cooked and ate dinner in the protection of my tent.

The sky was not colourful at sunrise (or sunset), although the golden rays of dawn lit the flowers beautifully. I have to admit I was SORELY tempted to stay in my warm sleeping bag and not venture into the frost outside, donning wet socks and shoes to do so, but I told myself I’d gone to a lot of effort to be here, and that really, it would be dumb to stay in my tent. I begrudgingly roused myself and put on every layer of clothing I possessed, wiped away the coating of frost on the tent, and got on with the day’s business. Of course, I was glad I did. One can stay in a warm bed almost any time, but one can only get up and witness sunrise on Tasmania’s highest mountain on very few occasions of one’s whole life. And life, I know, is a privilege not to be squandered.

The sky was not colourful at sunrise (or sunset), although the golden rays of dawn lit the flowers beautifully. I have to admit I was SORELY tempted to stay in my warm sleeping bag and not venture into the frost outside, donning wet socks and shoes to do so, but I told myself I’d gone to a lot of effort to be here, and that really, it would be dumb to stay in my tent. I begrudgingly roused myself and put on every layer of clothing I possessed, wiped away the coating of frost on the tent, and got on with the day’s business. Of course, I was glad I did. One can stay in a warm bed almost any time, but one can only get up and witness sunrise on Tasmania’s highest mountain on very few occasions of one’s whole life. And life, I know, is a privilege not to be squandered.

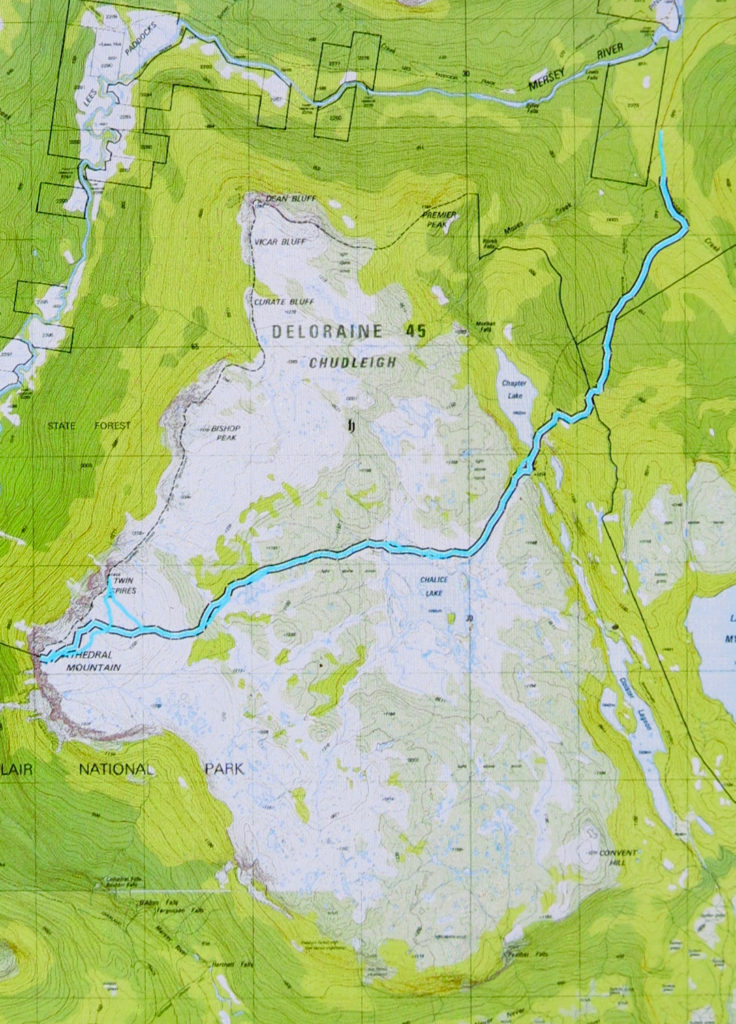

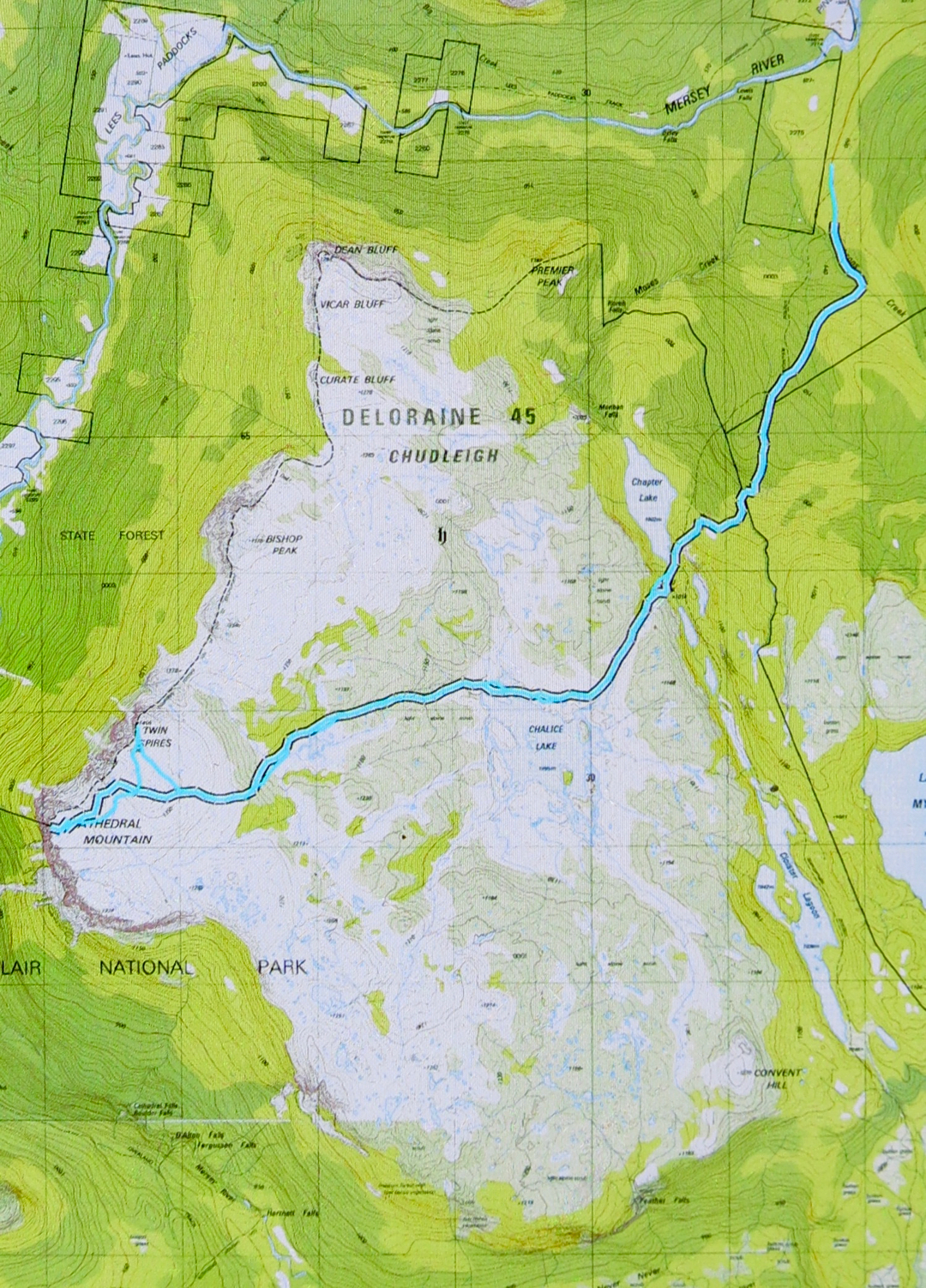

But you, lucky reader, can presumably visit this wonderful summit without these cares, and the majesty will have more power to impress you. Getting to the top involves a combination of track following and navigation. A rough (and not always distinct) path leads from the carpark at the end of the Lake Rowallan Road to the beautiful Grail Falls, after which a cairned route takes over, getting you as far as Tent Tarn. If you are not a confident navigator, you should stop here (or even earlier, by one of the other beautiful lakes). From Tent Tarn to the top, there is a route which is cairned, but the cairns are not always as close together as you might like and you do need to know what you’re doing in between their guidance. You need to be happy about branching out and not caring if you don’t find any more cairns today. (For the climb of the next day, Twin Spires, see separate post,viz:

But you, lucky reader, can presumably visit this wonderful summit without these cares, and the majesty will have more power to impress you. Getting to the top involves a combination of track following and navigation. A rough (and not always distinct) path leads from the carpark at the end of the Lake Rowallan Road to the beautiful Grail Falls, after which a cairned route takes over, getting you as far as Tent Tarn. If you are not a confident navigator, you should stop here (or even earlier, by one of the other beautiful lakes). From Tent Tarn to the top, there is a route which is cairned, but the cairns are not always as close together as you might like and you do need to know what you’re doing in between their guidance. You need to be happy about branching out and not caring if you don’t find any more cairns today. (For the climb of the next day, Twin Spires, see separate post,viz: