Mt Sorrell Mar 2015.

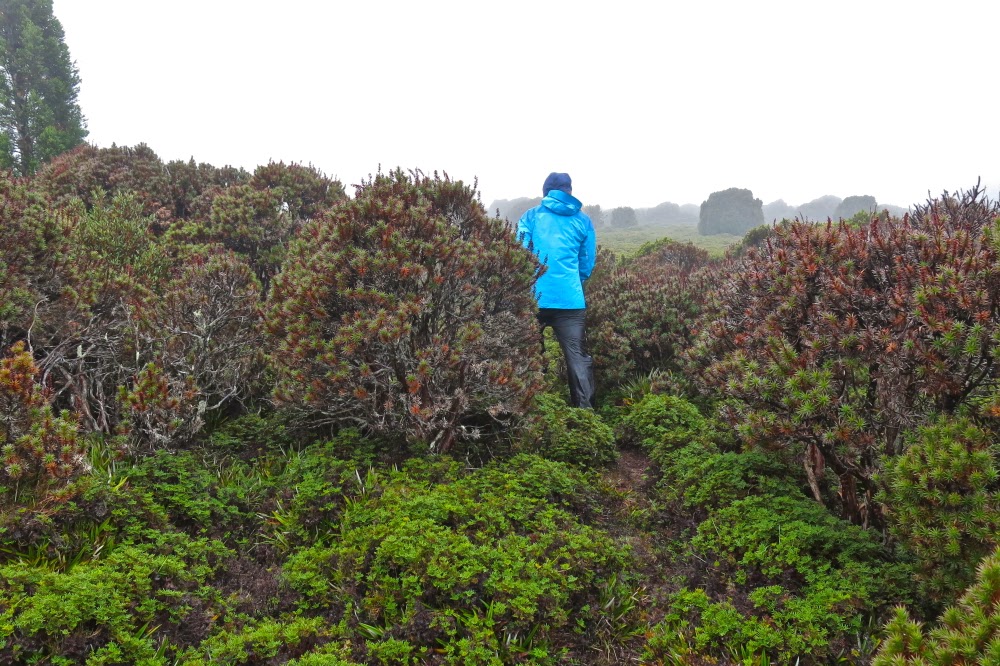

This is the slope we were negotiating

Mt Sorell has a formidable reputation. For that reason, the three men I was climbing with had left it until nearly last on the “to do” list of climbing all the Abels (peaks over 1100 ms in Tasmania). Of the 158 Abels, it was Andrew’s second last peak, and Terry’s fourth last. In fact, this would be Terry’s fourth attempt at the mountain. It does not give away its summit easily. These two men, on their first attempt four years ago, spent a whole day “punching holes in the scrub” to create tunnels of thoroughfare and laying tapes so that future attempts would be easier. They were. Because of their tapes, a couple of brave parties have gone through, finding the going much easier than they had done, and in the process, creating signs of human wear here and there (but not too much or too often) which now makes the going easier. But do not take this mountain for granted. If you think Mt Wright is too steep, then don’t bother with this one. It is not only steeper, but perilously slippery in wet weather (which we had). Route finding, even for the original tape layers, is not easy!

Another view of the kind of terrain we contended with

The forecast for our attempt was mixed: OK Saturday morning; furious rain Saturday afternoon; possibility of showers but also the possibility of clearing on Sunday. That would be our attempt day. On Saturday, we just got ourselves into position and sat out the drenching rain. Mark and I amused ourselves by counting the leeches crawling up the outside of the inner layer of our tents, calling out numbers to each other across the distance between our tents. Mark teased them, putting unattainable fingers on the other side of the fabric, but very near. Whenever either of us put a hand into our vestibule to get, say, our mug, our hands would be covered in leaping leeches before we’d even had time to grab what we wanted. I tossed up whether it was worth the price to cook dinner. Could I flick them off faster than they leaped onto me? I certainly did not dare go to the toilet. My crocs in the vestibule were covered in dancing, writhing, eager searchers for my blood.

A view from higher still … but there’s still plenty left to do.

Down below, Andrew and Terry had no leeches, but were fully occupied digging trenches and sticking holes in the metaphorical dykes to prevent the water flooding their tents. When Mark and I found that out next day, we were very glad to have camped on “Sorell heights” rather than the more protected bowl below. My tent changed shape dramatically with each blasting gust of wind, but that’s better than digging trenches in a storm.

The final saddle on the ridgeline before the summit. use that little bit on the left to climb and we’re there.

In order to make sure of the summit, our departure time was set at a sensible 7 a.m., and, as it was to be a 12-hour day, this was a good thing. We breakfasted in the dark, and set out at first light, through the wet scrub of the lower slopes. Up we climbed. It seemed pretty steep, but the experienced Terry and Andrew told us “we ain’t seen nothing yet”. OK. Mental reorientation. Soon enough we entered what they called the “tunnel of love”. This had taken them hours and hours to forge on that first, momentous trip. Now, thanks to their work, we were able with little effort to burrow through what would normally be energy-sapping, almost debilitating and demoralising scrub. One look to left, right or above and you appreciated the time and effort that had gone into this tunnel. Soon, they said, the hard work would begin. Pity. I had thought I was working pretty hard already. Then began talk of exposed rocks. Oh dear. What was this day going to bring?

Another view of the final saddle … just because I love the texture and form of rocks

Towards the end of the tunnel, we began to enter territory so steep that the next step involved hauls up 2 ms of slippery mud or sheer rock. I tugged for all I was worth on roots or bushes but sometimes that wasn’t enough. At least five times, I needed Mark’s friendly hand offered to give my muscles that extra oomph to ascend the otherwise unascendable. Oh dear. Frailty, thy name is woman. I could do nothing about it but be grateful that these guys had invited me along. Did they realise I’d need occasional help?

Summit view of the land below. (Grand vistas were, unfortunately, not well delineated thanks to the abundance of moisture in the air).

I don’t have many photos. We were very task-oriented that morning. Our goal was the summit, and the only breaks were one toilet stop for two men (whew, a chance to take photos for me) and one stop for shedding a layer (more photos for me). Apart from that, it was purposeful progress directed towards the summit. Once we breasted the ridge, with about 1.25 kms remaining to traverse the tops to the actual summit, the going was, of course, easier, and then there was a tiny climb (144 metres) up the last, pretty easy slope.

Two of the others approaching the actual summit from a rise that I had thought, whilst climbing, would be the real summit. I love photos that put tiny humans into the perspective of the grandeur of nature.

I went right of a creek, the others set out left. The sun was in my eyes so I could see very little and lost track of whether the others had crossed over to my route or had remained left. I couldn’t see them, and no longer knew if they were ahead or behind, but figured we’d connect with each other on the summit. With excitement I viewed the trig, but didn’t go any closer than twenty metres to it. Terry and Andrew had forged the track. Without Mark’s hands I would not be where I was. I wanted to be the last to touch the actual goal of all this effort. I was the one who had done the least. I wasn’t even sure how or why I had been invited, but I did know I was exceptionally grateful.

Crossing Clark River on our return

It took us four hours from the tent to the summit. We had time there to indulge in photos and food before we began our descent, but even then, we didn’t waste too much time. Our goal was won, but our job was not yet done. This was to be a big day. Luckily, the bum slide down the mountain was very quick: a mere two hours of pretty good fun, which meant we could relax a tiny bit to eat lunch and pack up our tents before the next stint of climbing back up to the Darwin ridgeline and dropping way, way down to the cars at the start, a trip that would take us 3 hours plus a couple of stops. The river had flooded a bit overnight, so some time was lost sorting out the best crossing point. I just wanted to keep my camera and sleeping bag dry (translated: I didn’t want to fall in) and was prepared to get my feet very wet in order to prevent toppling in a misguided attempt to be fancy by trying keeping my shoes dry. My boots were sodden and made rude, slushing noises for the rest of the trip.

This is the way I, too, chose to cross: maximum water logging, minimum risk of falling. I didn’t want to leap across slimy rocks.

At last we got to the cars, made it to Queenstown to find all opportunities for real food had already closed, so settled for a meat pie to fortify us for the very long trip home. I drove to the “wild life highway”, and Terry did the rest. I tried to stay awake for his sake, but rather fear my talk sounded like that of an inebriated fool – slurred and not terribly sensible. I was aware of dropping off mid sentence at times, possibly with increasing frequency as the time snuck over the midnight barrier. We pulled in at something near 1 a.m. The dinner Bruce had made, hoping for an earlier arrival, smelled good. I don’t often have midnight feasts, but succumbed this time.

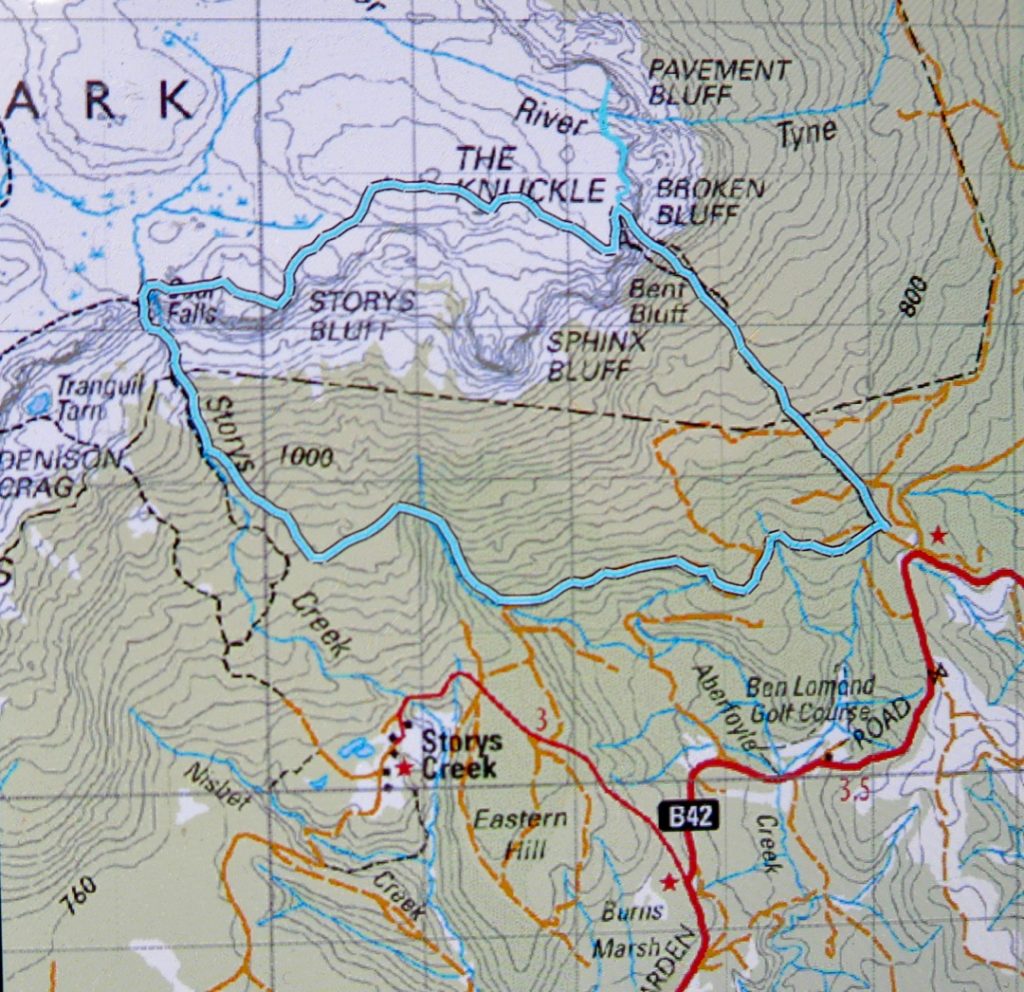

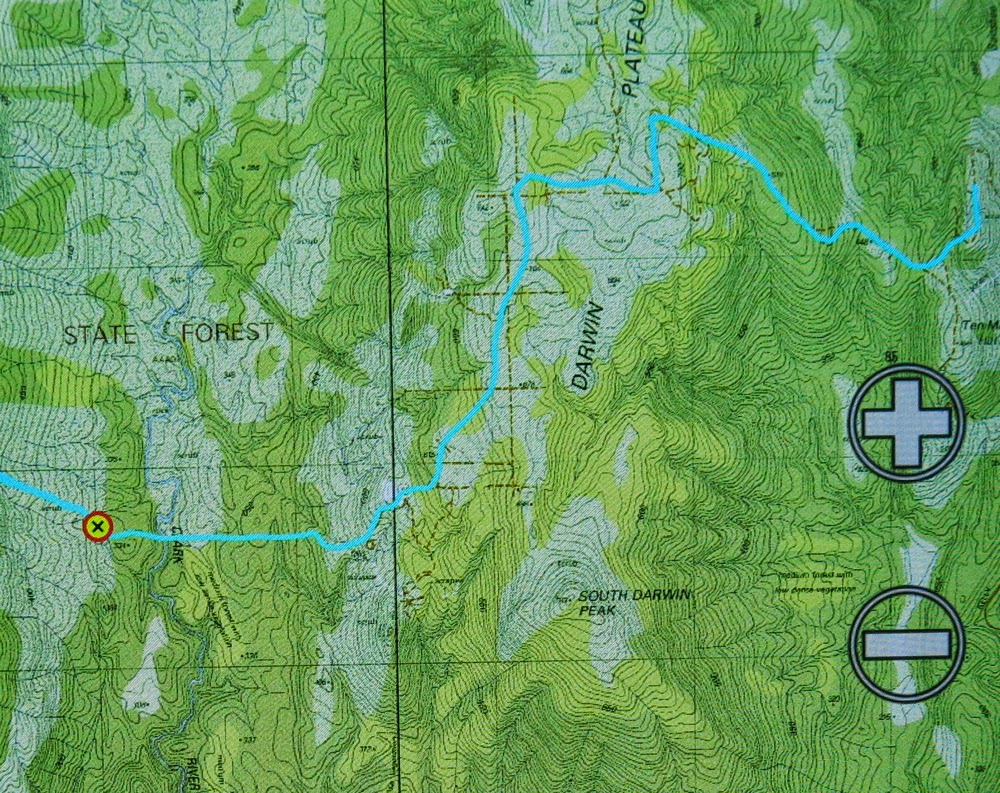

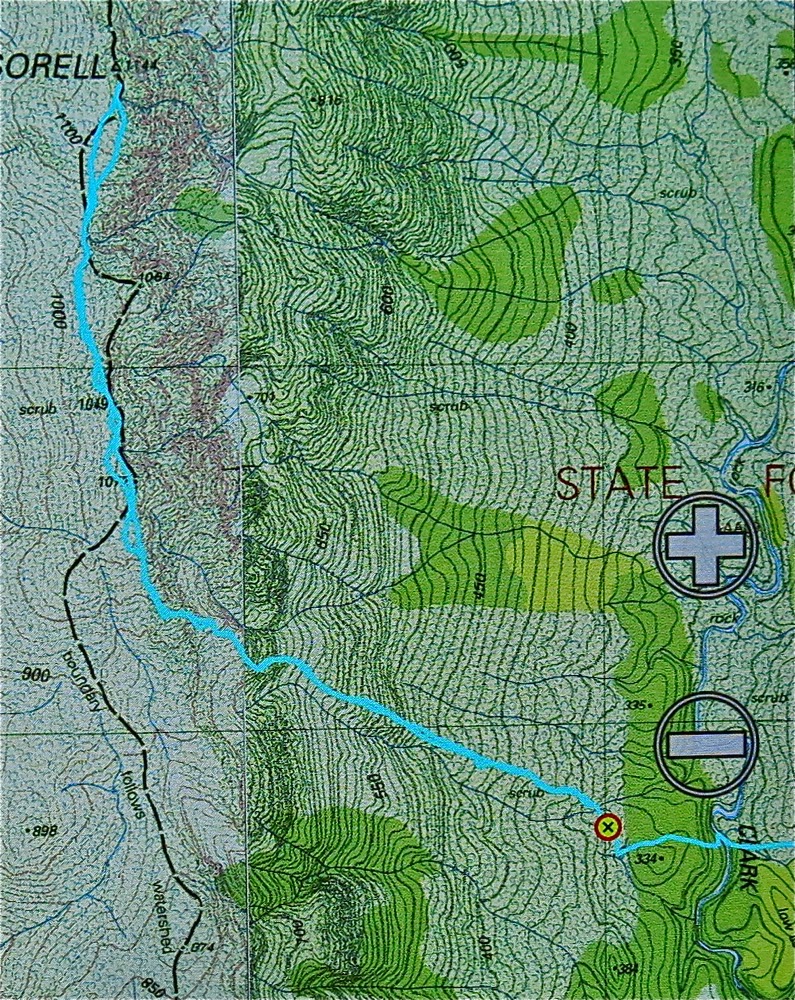

This is our route from the car to the tent site (and return later the next day

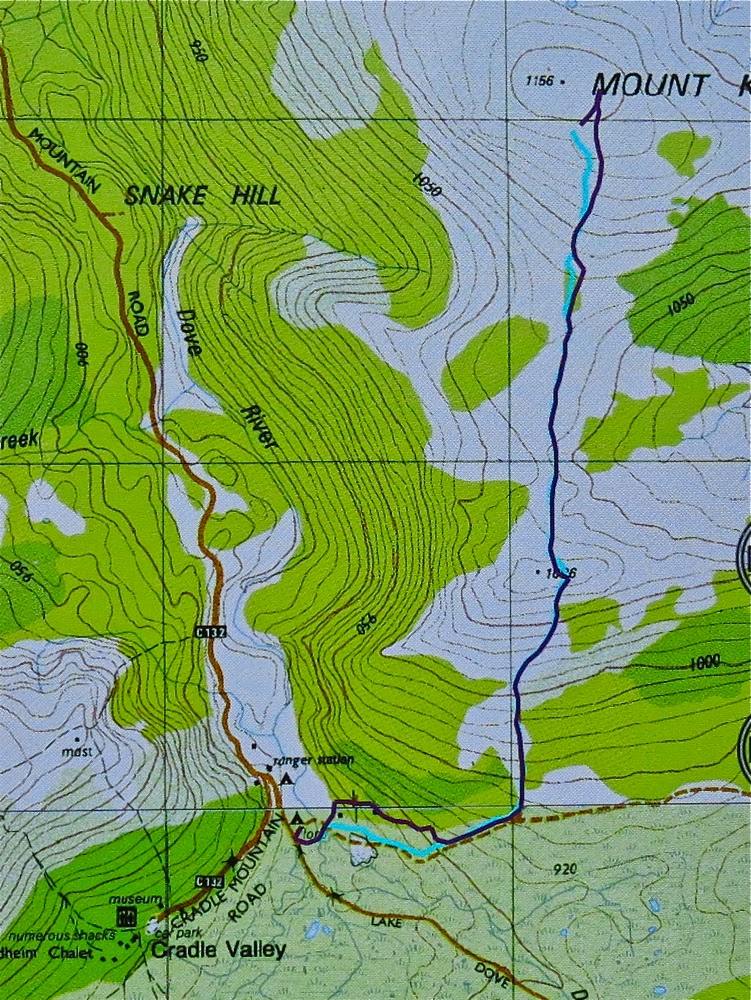

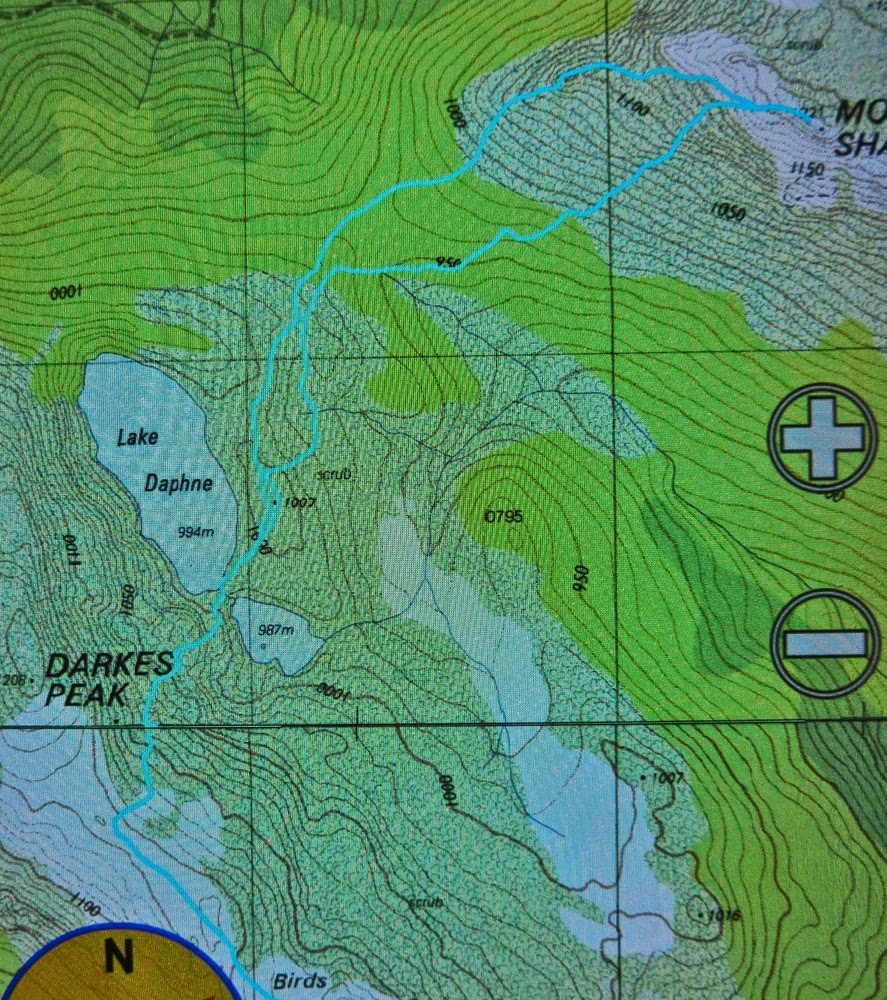

And this is our route from the tent site (waypoint) to the summit return. You will note that the contour lines are so close together they just make a brown smudge on the map.

Track data: All up, just on Sunday, we walked 17.8 kms, and climbed (and dropped) 824 ms + 467 ms. This yields a total of 30.7 km equivalents for the day.