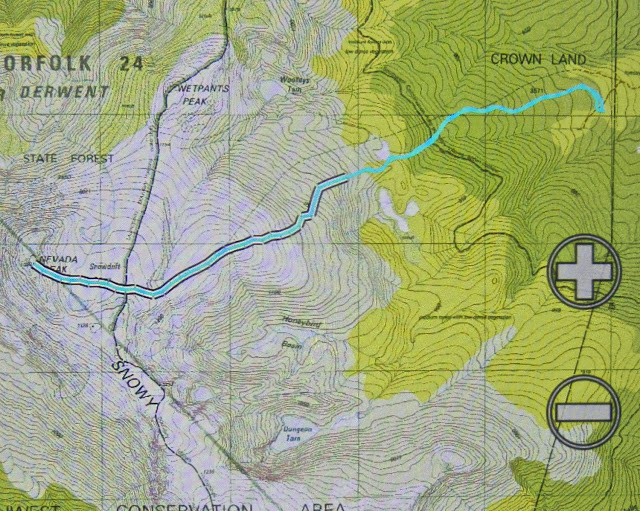

Florentine and Tyenna Peaks: Sleeping on top. 6-7 Sept 2014.

On the approach to Florentine Peak

On the approach to Florentine Peak

Our feet crunched noisily on the snow as we made our way over the Rodway Range, our overnight packs on our backs. Mist played around us, sometimes teasing us with a view of the rocks around, at others enclosing us in a world of grey. We hadn’t set out from the car until after lunch and, according to BoM, the weather right now should have been fine, but this dense air wasn’t cooperating.

“I think we’ll have to switch to Plan B,” I muttered a short while later as we crabbed our way along the slippery descent from the high point, made treacherous by the moist black moss. “I don’t want to lug this gear up a mountain we can’t see and don’t know.”

My husband kind of grunted assent.

As we approached K-Col, however, I changed my mind. There was no sun and the wind was up, but we could at least now see our intended mountain, and you never knew what tomorrow would bring.

“Yeah, let’s give it a go,” Bruce agreed.

Beautiful cushion plant, with FP behind.

Although The Abels book suggested a slightly different route, I was in the mood for climbing, so we set off straight up the first mound, using channels of vegetation, which eventually produced a kind of climb-contour alternation to the first saddle, after which it was straight up on all fours – very steeply. My husband suffers from vertigo, so I hoped he wasn’t looking over his shoulder. He was … and so began moving very slowly, which he does when the fear factor kicks in. By the time we’d reached the cairn of that particular summit (nicknamed by me ‘summit 2’, as it was the second highest of the several wonderful mounds that decorate the Florentine general lump), he was ready to stop. “Let’s call this the summit,” he suggested.

Straight up and still smiling.

“No. It’s not the summit, and I’m going to the real one. But this is a great place for camping. I can pitch the tent here if you’d like.”

He liked. I pitched. Time was now running out and I was getting frustrated and upset. I still hadn’t earned any points at all today and Bruce wanted us out by lunchtime tomorrow. We were on a summit, but it was 10 metres below the actual one, which still looked (as from the map) about a kilometre away.

One of very few sunset photos, taken on the way back.

I erected the tent hastily, threw a few things into my daypack and was ready to try for my first points of the excursion. Bruce was now feeling more enthusiastic, so was ready to come too. Off we set at a rush and to my absolute astonishment, we were standing on its summit celebrating in under ten minutes. Hoorah. Time was still at a premium. We only took one photo up there, as we decided we could give Tyenna a try as well, given the speed with which we’d summitted Florentine. People said it was an hour in each direction. We had 1 hr 45 until total darkness. It was worth a go.

We literally raced where we could – along the vegetation leads, running until Bruce took a few falls, so then slowing to a quick walk. Twenty five minutes got us as far as a high point overlooking the final saddle separating us from our goal. There was no way I could get Bruce up and back before darkness fell. He agreed to stay there and watch, and have a rest. The terrain looked rather unfriendly ahead.

Looking back at Tyenna once we were reunited

The going was slower now, as the bush had thickened up here, and the rocks were once more slippery and jagged. As I climbed higher, the gaps between rocks were sometimes 4-6 metres deep. Despite the need for haste, there was also a paramount need for care. If I fell, I would probably freeze to death overnight, and Bruce wouldn’t have any idea what to do and would be stuck out in the open as well. The forecast was for frost in a town 1200 ms below us. Who knows what the temperature would get to up there? Three times I ended up in a cul-de-sac of unclimbable cliff-face, and had to back track, sidle around further and try again. I didn’t want to look at my watch until I reached the top, as I didn’t want to have to turn around before my goal, and I had a strong sense that I did not wish to see the information it would tell me.

Sunrise from our wonderful eyrie

I had been right. When I finally got to the top and looked, I had taken too long in dead-ends and caution. I needed to hurry back, but still needed not to land at the bottom of a rocky crevice in a single misjudgement or patch of unexpected slippery black moss. I negotiated obstacles on all fives, a monster crab descending, and then hurried to my husband in his bright orange jacket, a wonderful beacon on the horizon catching the now golden rays of the sun.

Looking to the Mt Anne group. (Feder is visible, faintly, to the left)

In all this time – since leaving our tent – I’d hardly taken any photos, such was our emphasis on speed to beat the darkness. Our tent was maybe 45 minutes away, and the sun was setting. However, we were also now out of danger. It would get dark, but we were once more together with nothing more to climb, and I could navigate us back to our tent. I’d taken a very careful note of the shape of our summit (which, being the furthest away no longer looked as high as it actually was, so I couldn’t just head for the second highest lump); I had also been observant about the shape of the snow patch we were next to (and I did have my gps as a backup for emergencies).

Looking across to Florentine summit 1

I steered us along the western cliff line, partly because that gave us the most light, but mainly because it gave us the best view of the sunset that was now in full swing. Now we were reunited, I used the moments where I waited for B to catch up to snatch brief photo opportunities, although I still had no time to think carefully about composition or lighting. It was, out of necessity, a matter of point and shoot. It was such a shame to be wasting a glorious sunset careening through the landscape, but I would not loosen my guard until our tent was in sight. I feel very responsible leading a man with Parkinson’s in situations like this. The few photos would at least let us admire our sunset later.

A different view of Florentine from Florentine. (See Mt Solitary there to the left).

By the time we were about ten minutes from the tent, it was totally dark on the ground, but we could observe shapes against the horizon. Luckily I knew the form of our patch of snow, as it guided me in to the control point of our tent. I was basically on top of it before I noticed it. Bruce was still in earshot, so my voice guided him in (I never let him get out of earshot). Now we were both there, perched on our eyrie, we could enjoy the remnants of the red and tangerine sunset out to the west. Florentine summit 1 had a beautiful mist floating around its head. Everything was ethereal with that light, dancing veil. We felt transported into a world of glory.

View towards Mt Field West.

Perhaps it is odd of me, but one of the aspects of summit camping that I adore is the inevitable 2 a.m. need to get out of the tent and go to the toilet. The air is so crisp at that hour and the silhouettes of mountains always particularly sharp. As I emerged from the tent, the stars glistened and flickered in a sky that was now perfectly clear. The moon picked out the delineated edges of the pineapple grass fronds, underlining each one in shining silver. I stayed outside as long as I could considering the cold, gazing, fully-satisfied at the spectacle of near perfection around me.

Looking at Mt Mueller. Our tent and its ice-block tarn in the foreground.

But the very best thing about summit camping is the dawn. This dawn was superlative. First we had a gentle alpenglow, followed by ruby highlights as the rising sun touched the dolerite rocks around as we perched on our summit gazing out in awe. Fluffy, puffy clouds filled the valley below. We could see all the Western and Eastern Arthurs, the Mt Anne group, Lake Pedder with Mt Solitary peeping through between Florentine lumps, last week’s mountain (Mueller), The Thumbs and more. It would be impossible to actually count the number of peaks in our purview, each one taking form as an indigo silhouette against a pastel roseate background.

Looking towards The Thumbs across a sea of cotton wool.

I was completely fulfilled as we returned to the tent (2 mins away) to cook breakfast. But here we encountered a problem. Last night, I was already tucked in my sleeping bag when I remembered that I really should fill my water bottle so we’d have running water for breakfast. I was too snug and too lazy to get up – and didn’t want to wet my fingers. I was quite cold enough by this stage. The price we paid for that inertia in the morning was that we had no water for our porridge. I watched as Bruce tried to bang things against the ice on the tarn with no effect. I suggested a sharp rock would be the only means, so he procured one and hammered the sharp end into the ice. Bang, crash. Still no resistance. Fourth time, he met with success and succeeded in breaking a patch of the very thick ice. What emphasised the degree of cold that existed overnight was the fact that ten minutes later when I went to the hole he’d made to collect water for coffee, it was an iced-over scar, a reminder of where a hole had been, but a hole no longer. I had to boil our cups to get the solid ice blocks out of them.

And finally, looking back towards last night’s mountain, Tyenna Peak.

We were back at the car late morning, allowing us to have lunch at the Possum Shed, and be in Launceston by mid-afternoon, which was needed for work reasons. It was a pleasant change to arrive home in the light, and the dogs were thrilled. They cavorted with us in the garden before we settled into other duties.