Rocky Hill 14-16 May 2017

We never doubted that we’d make it, but it was still an enormous relief to crest the final rise that led irrevocably to the summit of Rocky Hill. This was the second time the two of us had climbed Rocky, but was the first time we’d seen its rather elusive view. Clouds seem to enjoy Rocky Hill just as much as we do, and it pleases them to tease would-be view seekers.

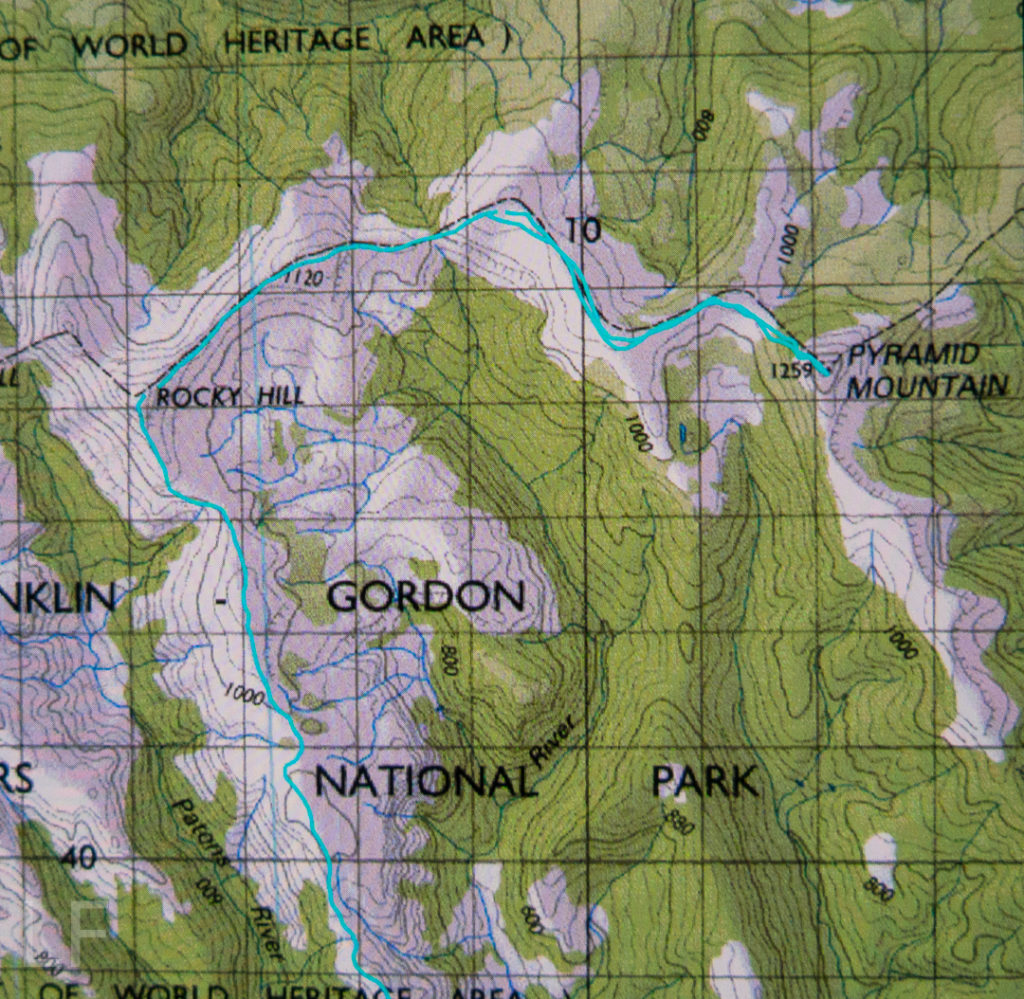

It was so worth the day’s effort to see what we were now seeing: viz, a vast array of magnificent mountain friends, almost all of which we’d climbed, although not all of which we could readily name from that angle. In particular, we adored the different perspective on Eldon Crag and Peak; it was also amazing to see the seemingly ubiquitous Frenchmans Cap, which must be the “most seen” mountain in Tasmania. Way to the north east, we could see as far as Cradle, Barn Bluff and Emmett, as well as Pelion West, Ossa, Thetis, Manfred, Cuvier, Byron, Geryon, Acropolis and Olympus – in fact, the bulk of the mountains that line the famous Overland Track. This was not a view that you just noticed and then departed from. You had to stay for a long time. We bounced around with delight, and stayed all night. Well, in fact, we stayed two nights, so good was the view. The fact that we’d arrived up there by 3 pm meant we certainly had time to progress further along the ridge as far as Mediation Hill, but we were in love with this spot, and we stayed put. We thought we could make it to Pyramid Mountain (our next day’s objective) and back from there, although it was a slight gamble given the short days at this time of year.

It was so worth the day’s effort to see what we were now seeing: viz, a vast array of magnificent mountain friends, almost all of which we’d climbed, although not all of which we could readily name from that angle. In particular, we adored the different perspective on Eldon Crag and Peak; it was also amazing to see the seemingly ubiquitous Frenchmans Cap, which must be the “most seen” mountain in Tasmania. Way to the north east, we could see as far as Cradle, Barn Bluff and Emmett, as well as Pelion West, Ossa, Thetis, Manfred, Cuvier, Byron, Geryon, Acropolis and Olympus – in fact, the bulk of the mountains that line the famous Overland Track. This was not a view that you just noticed and then departed from. You had to stay for a long time. We bounced around with delight, and stayed all night. Well, in fact, we stayed two nights, so good was the view. The fact that we’d arrived up there by 3 pm meant we certainly had time to progress further along the ridge as far as Mediation Hill, but we were in love with this spot, and we stayed put. We thought we could make it to Pyramid Mountain (our next day’s objective) and back from there, although it was a slight gamble given the short days at this time of year.

It being so delightfully early, we had the luxury of exploring our little demesne for the night, to suss out snow drifts as a source of water and hunt for the best yabby holes. We spent a whole hour just gathering water for the next two days so that if we got back in the dark the following day, we wouldn’t have to go searching for liquid in order to cook, but could collapse straight into our tents. Our fabulous grassy patch was just below the summit, but, unlike the summit, was soft and lush.

As we slowly pitched and did all the activities associated with turning our chosen bit of mountain real estate into “home”, the clouds rose up in drifts from the valley below, turning more and more golden as the hour advanced. They were soft, wispy clouds that only partly veiled the mountain silhouettes around. Right at the peak of the drama, the ones above turned quite a strong dusky pink; it was a beautiful scene that I will never forget.

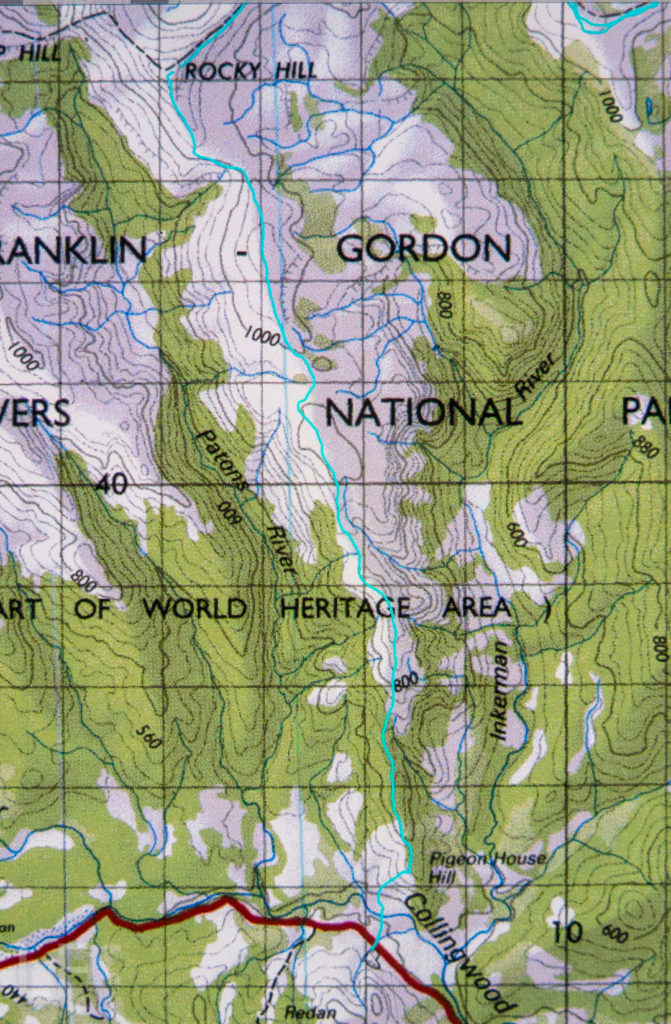

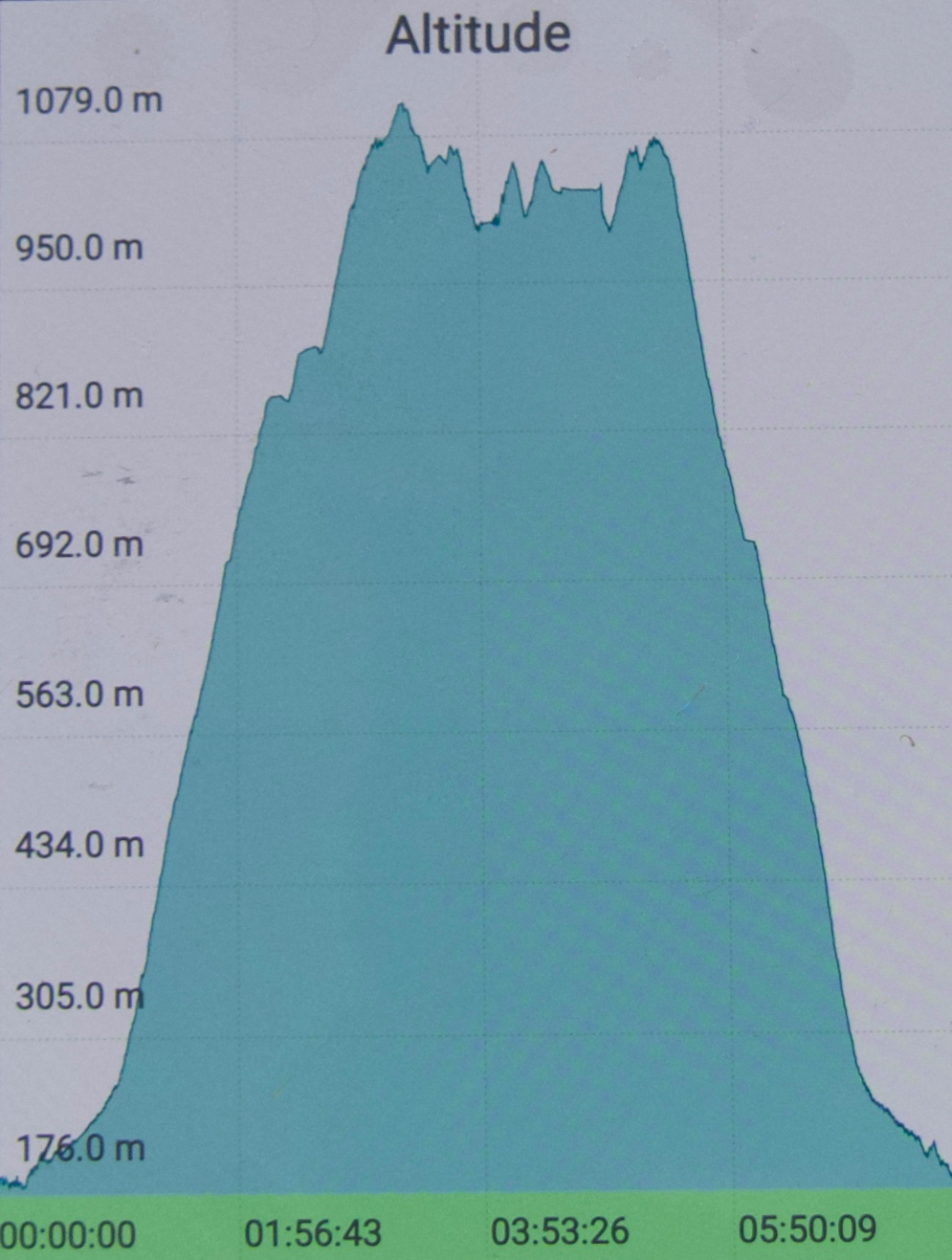

I don’t know why I had been so scared about crossing the Collingwood River at the start of the day. I guess I knew in advance that the temperature would be sub-zero, and that the river would not be summertime-low. It was, in fact, minus one, and upper-thigh high. Brrr. My main fear, of course, was slipping on the mossy rocks due to the force of the water, and falling in and getting hypothermic. I very sweetly let Angela go first to give me courage. It didn’t look easy as I watched her steadying herself, both arms out for balance. I grabbed a stick to help, took a huge gulp, and followed. I went in deeper than she did, mainly to keep on rocks that didn’t look as slippery. I made it, but my bottom half was frozen. Off we set up the very steep Pigeon House Hill. Surely that climb would warm us up. It warmed up everything but our feet; they took a little longer. By lunchtime they’d thawed, but, of course, they remained wet for all three days.

We found some random tapes on Pigeon House. We couldn’t work out where the person who put them there was going, but fortunately there weren’t too many. They took one onto the thickest part of the ridge, whereas the pad of least resistance, and the old route, skirts around the top at that early stage. We backtracked to find old cuts and used the old line instead. It was much easier going. If you are new to bushwalking, please don’t interpret that as “Oh goody, there’s a track up there. Let’s go.” Unfortunately, what I am referring to is small traces of where people have gone on some distant past occasion; you use broken or cut branches or other signs of humans passing (disturbed bark) to pick your line, and you have to have a very good idea of where you want to be going in order to gain from these signs. Please only venture into this untracked territory if you know what you’re doing and have a lot of experience. It is not for novices, or even for intermediate-standard walkers.

Once we gained the ridge past that early topping out, the going was easy for a little while, until our second “top out”, about an hour later, when we emerged from the beautiful forest onto a scrubby hill. From then on, for what seemed a long time, we had to lift our legs very high in a goose-step and at times force our way through higher patches of scrub: nothing too bad, but it does sap your energy anyway.

We concentrated on choosing a good line, and worked hard through the scrubby bits, and eventually we got there. If you don’t know Rocky Hill, don’t be fooled by its deceptive name. It is not a hill at all. It is an Abel, which means it is higher than 1100 ms (1194 to be exact), with a significant drop all around. Already snow drifts were building up with winter on the way. Some tarns were iced over. And the views, as said, were magic.

Next day, we’d climb Pyramid Mountain if all went well (and it did. See natureloverswalks.com/pyramid-mountain/). It was a big ask, so close to winter with the shortened days, but we’d give it a go. Just in case we weren’t quite as successful as we hoped, we packed bivvy bags, torches and a warm jacket beyond the many bundles of clothes we were already wearing. I thought that if we were stuck out overnight with wet gear, a bivvy and extra jacket would not be enough to save me, but I took them anyway. As it transpired, we were back well before our curfew, and had time to play on, and photograph, the rocks on the ridge with our tents in sight, as the mist once more rose up the valley.