Expedition to Mt Tramontane, a mountain seemingly in the middle of nowhere, but within a day of the Murchison River on our approach side (from the east), and High Dome and the Amphitheatre to the west. This mountain is truly remote. We packed for an eight-day hike, just in case.

Pre-dawn scene from my tent on Cuvier, looking towards Manfred

Tramontane is a peak in the middle of total wilderness, surrounded by more wilderness. I hadn’t thought too much about climbing it until the wife of the leader bumped into me when I was running and asked me if I was going on the expedition. She indicated she’d like me to be there. I looked up the dates; it was feasible, so I put my name on the list. I have never before exposed myself to wilderness quite so remote as this or so very wild, so previously untrodden and so difficult to either penetrate or escape from should something go wrong. But let me begin at the beginning ….

Climbing up towards the Byron-Cuvier saddle

Day 1. The early part of the trip was easy if you ignore the fact that my pack weighed over 16 kgs and I weigh 44. That is not a happy pack to person ratio, but I was fresh and love climbing, so the trek up to the Byron saddle posed no problems. There we had lunch. Soon the real challenges would begin.

On the Cuvier shelf

23 minutes after leaving the saddle (and heading for Lake Petrarch) we came to “creek number two”, and it was time to hive off to the right (SW then W then NW) around the fat belly of Byron, through cool, delightful rainforest replete with tall, graceful pandanis and the occasional shining waratah. Only when we were about to reach the Byron-Manfred saddle did we encounter any nasty scrub (in the form of a seemingly impenetrable wall of scoparia that was thorn-in-the-face high). We found a tiny tunnel of opportunity and squeezed our way through to the relatively open ridge with low-lying scrub, mainly bauera, shining white in the sun. It was time for afternoon tea. (I later repeated this route – when we climbed GSL – and this time went higher, dropping down to that saddle and met no scoparia at all).

Descending Cuvier

The day was hot, and some members of the party were struggling with the heat as we traversed the ridge between Byron and Cuvier. Stops were frequent, but at last we climbed onto a ledge not far below the Cuvier summit. I loved it, and wanted to pitch my tent right on the cliff edge with a view. The others wanted protection and running water, so we separated. It pleased me to have silence and the space of infinity around me, to just gaze out wordlessly and imbibe the atmosphere of grandeur provided by my abode for the night.

Near my tent spot

The others were keen to relax and cook dinner, but I was all impatience for the summit by this stage, especially as I could see mist thickening around me. I wanted a view from the top and as much clarity as the day could muster. Food was of minor importance and I didn’t need rest. As no one wanted to come, I summited alone, taking 24 mins up from the camp to the top. At first I was sad that I had no company for the climb, but soon realised that I was enjoying being allowed to go at my own pace. Already as I gazed out from the summit, clouds were amassing and beginning to smudge the clarity of the mountains’ outlines.

My chosen tent spot was not for sleepwalkers: I was perched in a position where five steps from my front door was one too many for the continuation of life. I sat on the edge of the rock and cooked dinner, watching the changing light and the moving mist on the landscape around. Peace. Infinitude. Bird calls reached me from far below as my feathered friends farewelled the day with a beautiful nocturne.

Manfred, predawn

Day 2. I woke nice and early as is my habit and opened the tent flap, curious after last night’s cloud gathering to see what I would see. I gasped. What awaited me was a scene of great glory: below my perch was an ocean of white puff; emerging at various points above were indigo pointed peaks. In the sky were the glorious colours of pre-dawn glow. I wandered over what had become home, my temporary territory, climbing little lumps and bumps, getting views from this angle and that, floating on a sea of bliss. I photographed for 40 minutes as the sun slowly rose, changing colours as it did so, highlighting first this peak and then that, casting shadows of a different colour on the now pastel pink puff.

Mist in the trees below me

Half an hour after sunrise, the dong sounded from below: time to wake up and get ready for an early start one and a half hours later. It was so tricky trying to squash food (and clothes) for the next seven days into my XS-size pack that it took me the full quota of that time to achieve pack up.

My private paradise

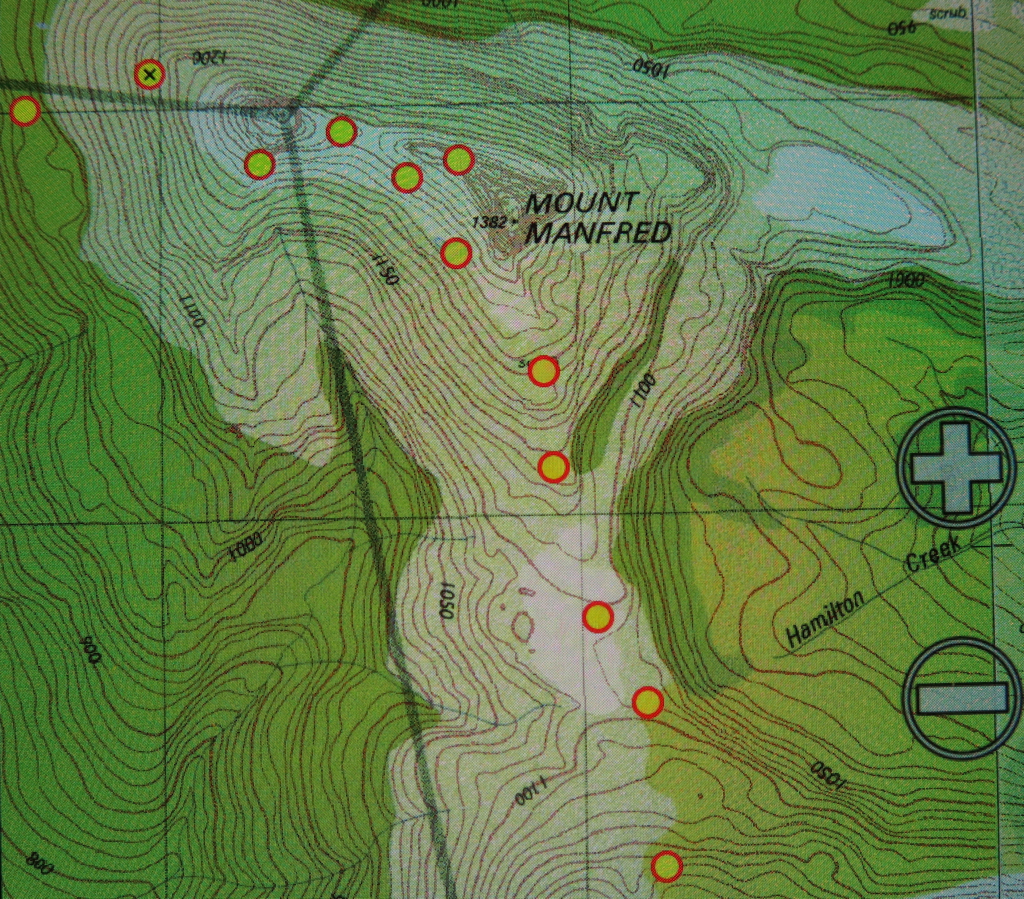

Off we set, heading just north of west down a hint of a scrubby spur at the base of the Cuvier cliffs that then swung around to be a better defined one heading more or less north, leading to a point just below the Cuvier-Manfred saddle (see map below). That scrub bashing was not the most pleasant of the journey. From that (Cuvier-Manfred) saddle, we climbed up through scrub that wasn’t nearly as bad as the original mini-spur until we reached the rocks at the base of Manfred, whence we began to traverse around the rocky section. However, when we saw the tarn below Manfred’s internal saddle, we looked at the alluring water and at our watches and voted for an early lunch. It was only around midday, but there was visible water and even a bit of shade. We dropped a contour or two for those treats, ate and then headed back up a quite nice lead with easy going to the actual saddle that separates Manfred from its other unnamed but very shapely half.

The first rays of sun hit Manfred

We all (ten of us) climbed Manfred together, choosing to approach the summit from the left (W). We were blessed with perfect clarity on top, and lazed around up there enjoying our vista.

And on the other side, they hit Cuvier

Now began the epic part of our journey, a travelling into rarely trodden land. At 3.15 we set out around the rocks of Manfred’s other bump (waypoints below) and thence down, down, down, at first through unrelenting, unmoving scrub, but then through glorious primaeval rainforest, treading where perhaps no human has ever trodden before, heading for the wild Murchison River.

The slopes were steep and slippery. Wood crumbled as you trod on it or held it for support, sending you flying. (Luckily I only did that once.) Many of our party hurt or bashed some body part, so that several were limping by the end of the day. Many knees seemed to have suffered. My former life as a goat stood me in good stead: my single fall left me unscathed. Five and a half hours after leaving the rocks, light had all but faded, but the river was not in sight. A gps reading said we had about 300 horizontal metres to go. Ah, 45 seconds you say? No.

Humans in the grander perspective.

About half an hour’s labour. It couldn’t be done before darkness obscured the traps that lay in wait for us. Our leader made the excellent call to halt and pitch camp pronto. I stared around wondering where on earth on a forty five degree slope covered in fallen timber you could find a place for a tent. In that time all available spots seemed to have been gobbled up. I thought I would just lie on forest debris all night as I watched the other pairs helping each other pitch. I was exhausted and there was so little light I didn’t dare wander too far from where everyone else was. Next morning one of our number was to get temporarily lost just going to the toilet, and that was in the light. The forest was deep and dark. Anyway, I eventually settled for a spot with a rock right where my chest should be, and, believe it or not, had a pretty good sleep, my diminutive stature meaning I could work around the rock and, all curled up, still have room of sorts.

View from the summit of Manfred

Day 3. First, we had to reach last night’s goal, the Murchison River. Even saying the name sent a frisson of anticipation down my spine. Once again, an early start was scheduled and for the most part, adhered to. We had a lot to accomplish this day, so it was with relief that half an hour brought us to its glorious banks. Many sat and stared at her while others of us scouted around for a camp spot. I headed to where I knew the spot from another group had been marked on my map (a group whose route had been further to the left (S) of our own), and there was space for us all, so off we went and pitched.

By 9 our tents were up and our daypacks ready for the next summit. First, we had to cross the Murchison, which we chose to do directly to the north, in line temporarily with a route Phil Dawson had once used.

Another summit view

The Murchison was not exactly hospitable to visitors, and two of our party had a brief, unplanned swim on the way over. They’d dry out as we climbed, very, very steeply, like cats on all fours, up this spur that is not part of the Tramontane massif, but adjacent to it, to its east. In parts on this spur the contours merge to become a brown smudge on the map. Climb, contour, climb, contour. Forward went our progress until we inched our way nearer to the NS-creek we needed to cross that would get us onto the Tramontane bulk, from whence we could climb our goal. All this was done in pristine, magnificent and perhaps previously unseen forest (given that our route now diverged from any that we knew had been taken before and that the groups that have climbed this mountain can still be counted without too much arithmetical skill – i.e., you need only to count to two). There were no signs of any previous human visitation; the first indication of other humans would occur much higher, nearer the summit.

Beautiful pandanis in the early part of the rainforest in the descent to the Murchison from Manfred

Once we were onto Tramontane itself, the going was much easier than expected. Although visibility in the moss-laded forest was not extensive, it was forgiving of our attempts to move through it, and we moved with good progress. Lunch was had a very short distance (maybe 200 horizontal metres) from the top, a spot selected for its view. The summit had waited for our arrival for an eternity; it could wait another half hour without getting impatient.

The Murchison at last

Shortly after we summited and took all the obligatory photos (and after I had reclined in the branches of a tree that allowed me to be maybe two metres above the summit, just for fun), steely clouds gathered and released two fusillades of hail upon us. Thunder grumbled all about us. Hail morphed to rain that then fell intermittently for the rest of the afternoon, sometimes lightly, other times with severity. By the time we got back down to the now swollen banks of the Murchison, we were pretty drenched and darkness was gathering apace. Lost in a tangle of horizontal scrub, and making little progress in the gloom, I began to fear that this was our spot for the night, but the story ends happily enough. Reaching impasse after impasse when trying to get around to the point north of where we had been camped in a retracing of our ascent route, the guy in the temporary lead and I suggested it might be better to try our luck at crossing the river further upstream than intended and seeing if it were possible to walk along the river to camp. There was a risk factor involved in experimenting in this way at this late stage of the day, but time was running out and everyone agreed to the route. It worked unexpectedly well, but only because of the assistance of Steve J and then others who joined him in helping those of us more easily pushed around by the forces of nature by giving us a stabilising hand as we went past the fiercest of the flow. I am always happy to see my little tent, but never happier than this day. My feet were even dry, although my clothing was pretty wet.

A photographer’s delight

Day 4. Every day up until now had involved very early starts and late finishes. Many of our party were now harbouring injuries of varying severity. Plans needed to be modified; besides, the river was wild when people visited it after emerging from their tents. A rest day was in order, and we revelled in it, many electing to sleep most of the day. I stayed put as it was raining and I neither wanted to don my wet gear, nor risk wetting my single dry outfit. When it wasn’t raining, but the forest was still dripping, I lay inside my tent with the flap open, just gazing at the beauty of the lush greenness. Housekeeping, in the form of attempting to dry clothes (unsuccessful for my part) was the most pursued activity of the day. My tent had leaked badly, and the clothes that were on the floor were now absolutely sodden. I ladled water out and fought uselessly to wring moisture out of the clothes. They were wetter at the end of the day than at the start. I was not looking forward to getting dressed the next day. Even my sleeping bag was wet where it overlapped my air mattress, a bright yellow island in the middle of a shallow lake.

View from the summit of Tramontane.

Day 5. Time to retrace our steps and head for home, having abandoned the Amphitheatre yesterday. With greater confidence, the benefits of rest and a dose of both good luck and good management, we made much better progress up the slope than we had made down, and what took us 6 hours to descend two days ago took only 5 to climb today. We reached the rocks at a time when the heavens looked angry yet again and lunch could be justified. We ate and rain began as we did so, getting heavier again as the day continued. The rocks weren’t as slippery as I feared, despite their black moss, and made a pleasant change from trying to push uselessly against trunks that wouldn’t give way beneath my feeble efforts.

A happy Caroline at the Murchison

Things only took a turn for the worse when we reached the Manfred internal saddle. Here, the gathering wind could unleash itself at us unhindered by other obstacles, and I began to freeze. Mist enshrouded us. Core temperatures dropped. We sidled past the cliffs of the summit section, heading for the main Manfred ridge projecting in a slight and irregular curve eastish (and a bit north) of the summit. This ridge has two main sections, separated from each other with huge cliffs, with other, smaller yet still challenging cliffs preventing one from taking a Sunday stroll along their length. We passed what I like to call the bowling green section: a field of the brightest green ground imaginable, with tiny ribbons of water running through that begged photography, but my camera was one of the many items to fall victim to the soaking my tent had received on the Murchison and no more photos were possible in this part of the trip.

Tent city on the banks of the Murchison

Soon enough, we hit a cup-de-sac, the first of the huge cliffs indicated by the contours on the map. We were by now sodden and freezing. My hands had lost so much power I couldn’t even press the clips that undo sections of my pack. Mist reduced visibility to that within thick soup. These were not good conditions to be standing around experimenting with tricky descents into an abyss. Trial and error could be done at a better time than now. Our leader made the excellent call to quit for the day and retreat, even though it was only 3.30. Hopefully the morrow would bring some visibility that would aid our efforts. We set up camp in bushes close to the cliff’s edge. Out my tent flap, white heath flower glowed and sparkled. Every now and then a view of Byron graced me with its tachistoscopic appearance.

The view out my tent flap on the rest day. I stared at it all day and did not tire of it once.

I was so cold I couldn’t muster any interest in dinner. The very thought of it made me nauseous. I had a few biscuits and began exercises to warm myself up. Later I forced down a square of chocolate. My sleeping bag was wet (the sodden bits had shared their moisture in the pack with the drier parts) and I hoped activity might help dry it. I dreaded the next day when I would have to don the wet clothes. If navigation decisions caused long delays while I chilled off in icy wind, I didn’t like my chances of survival. I wanted to call my husband to say ‘Goodbye’, just in case, but there was no signal.

Day 6. Thank God, quite literally, the decision was made to delay our departure until we had some semblance of visibility. Snow fell, but after that birds started singing, always a good sign, and at long last things cleared enough to name a departure time. A kind person who watched out for me arranged things so that I could get dressed last, and offered to take the tent down while I tugged on the repugnant wet gear, minimising my stationary waiting time, which was my downfall. This was a great plan, but we all then stood waiting for one tardy person for ten minutes, so it misfired a bit, but I sure appreciated the intention. Luckily, the rain had stopped and the wind had abated, so the chill factor was reduced. I was merely uncomfortable, which is not a threatening condition. We were away.

The rest of the day was absolutely grand, and a huge adventure. Descending the cliffs, now we had an inkling of how far each drop was as we could see the bottom, was an adventure with risk but no real danger – exhilarating. Down chutes we slid, attenuating our drop speed by using branches to retard us, sliding on our behinds in the mud in a whoosh to the bottom. Grandi. We eventually bumped onto the main Manfred ridge, and stared with glee up the cliffs to the spot where we had been camped for the night: perilous cliffs with vertical towering dolerite pipes behind. Oh how I wanted to photograph it!! What a brilliant ledge it was.

We lunched on this ridge before the next big plunge, although our confidence was now growing. Along we went, searching for a possible descent spot, eventually finding one we reckoned would work and giving it a hesitant go. Success. We were down and into magic, fairyland rainforest of moss and lichen and a magnificence that is hard to convey. It was a supreme privilege to have been in that place.

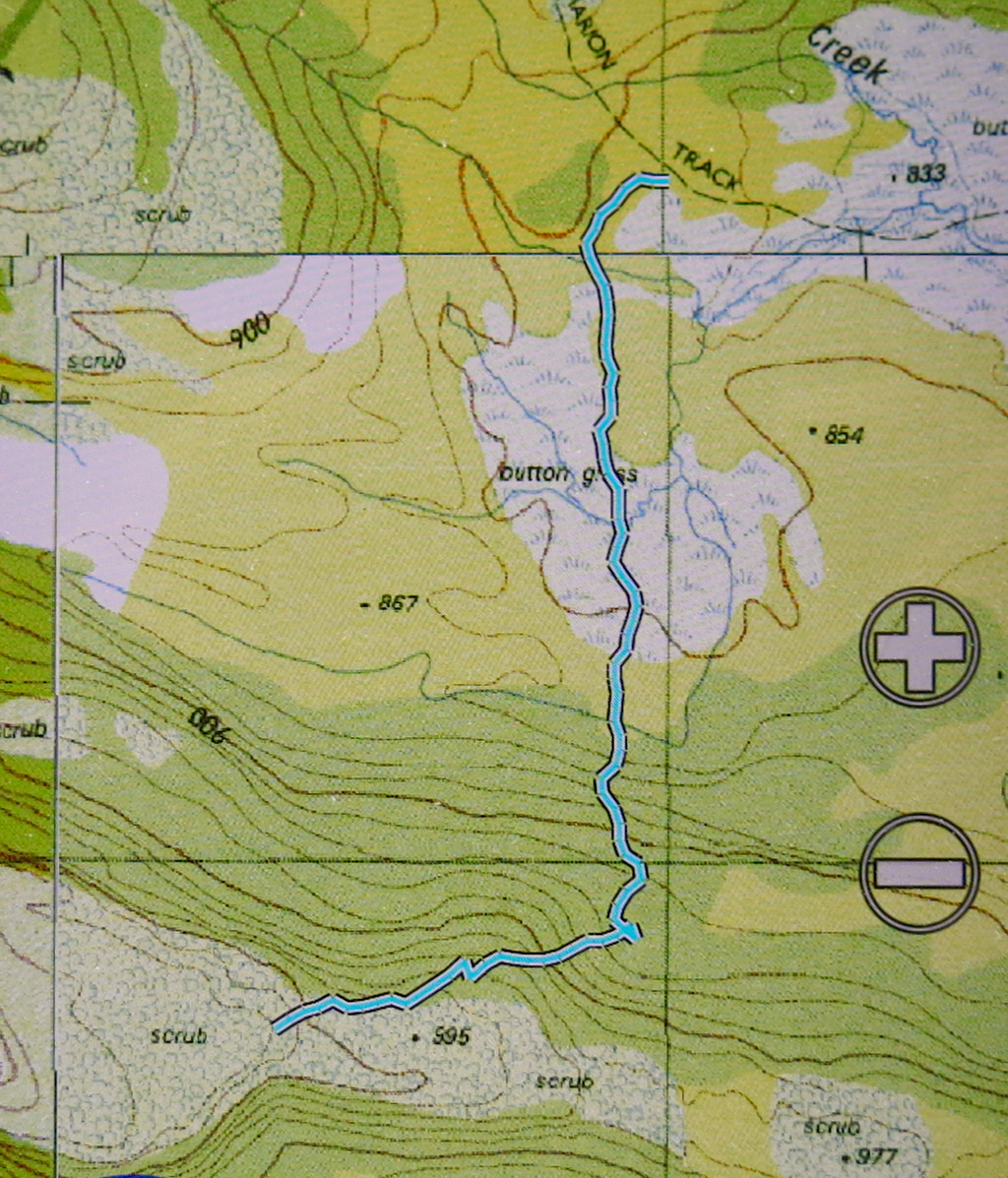

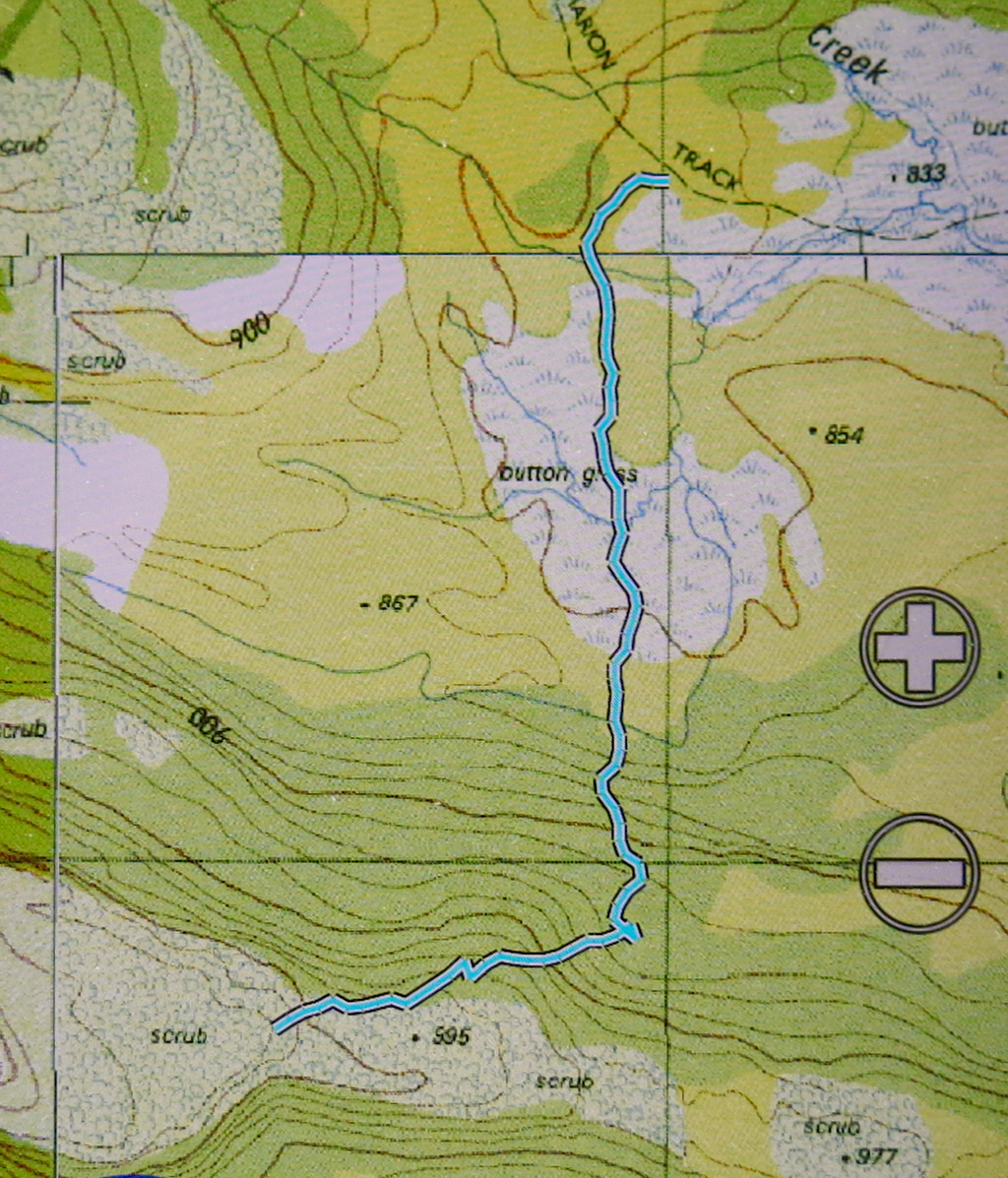

Eventually we emerged onto the button grass plains below. Eventual success was now in sight. The plains were surprisingly easy to traverse and soon enough we intersected the Lake Marion track. It was time to farewell four of our number who were going to climb Horizontal Hill.

A lone pandani plant catches the light

Six of us thought we were just about finished, but we were ignorant of the fact that the cute little tributary we had to cross twice was now uncrossable. At the first crossing, two of the guys broke off a huge branch, carried it to the creek and flung it over. We walked across safe and dry, but at the second crossing, we were all stymied. The flow was too fast, too deep and too wide for us to consider it. As this represented a double crossing of the creek, I suggested we return to the first crossing and bush bash higher up, avoiding all crossings. The others agreed, so back we went, heading across more plains to higher ground, negotiating other creeks that weren’t as flooded and with success we intersected the track as it entered the rainforest further down.

In possibly record-slow time, we eventually reached the Taj Ma Toilet of Narcissus Hut, riding high above the trees as a beacon. It was finished. High fives and hugs all round marked the end of our epic. The rain began again. I opted for warmth – I was over the adventure of pitching and depitching a wet tent and cooking – a prisoner of my own vestibule – to the sound of the patter of rain encroaching on my personal space, rain that lowered the sides of my tent to turn it into a triangular mini-coffin.

I elected to sleep in the hut, where I had warmth, walking space, a table and the pleasure of meeting ten friendly, interesting and fun people from Melbourne who had all just finished the Overland track. All our trials were over. Already hardships were becoming a theoretical fact that somehow belonged to some other story and what remained at the core of this one was a wondrous epic full of the grandeur of nature, a magnificence that somehow lets us transcend the puny perimeters of our epidermal layer, or even the broader horizons of our mind. Here is sublimity.

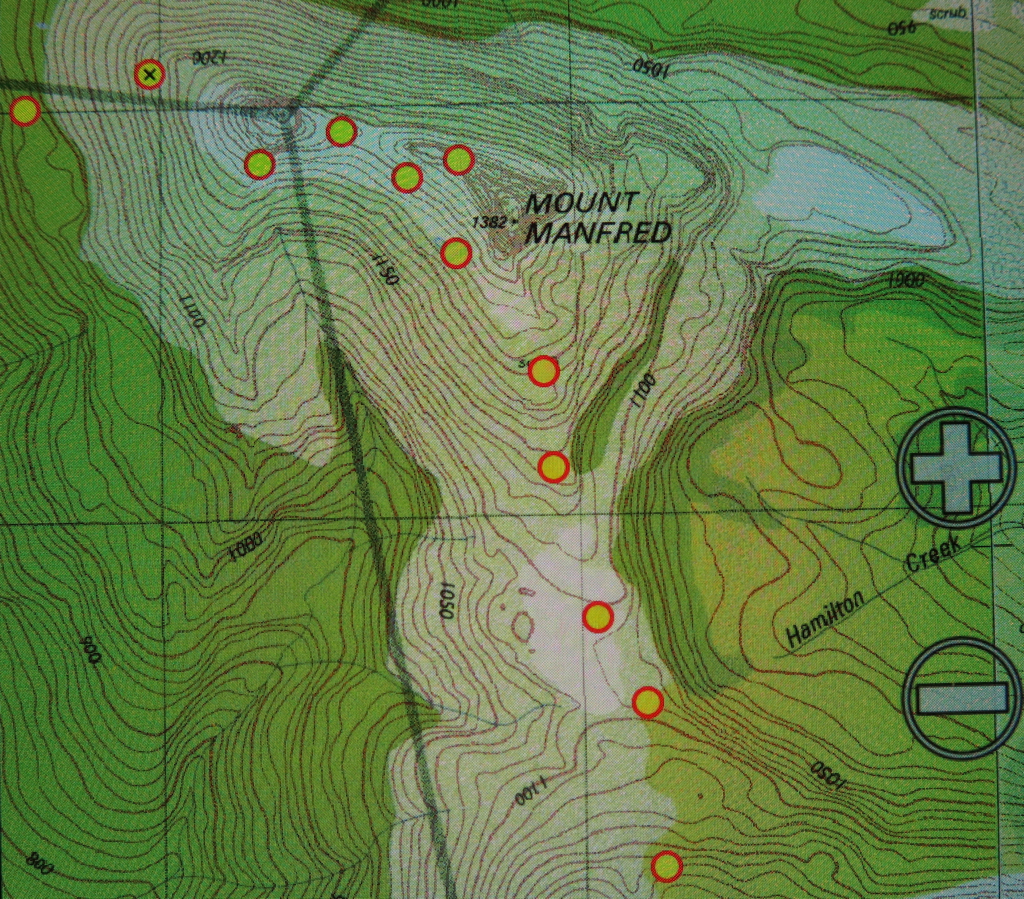

Descent off Manfred to the Murchison (camping on its eastern bank)

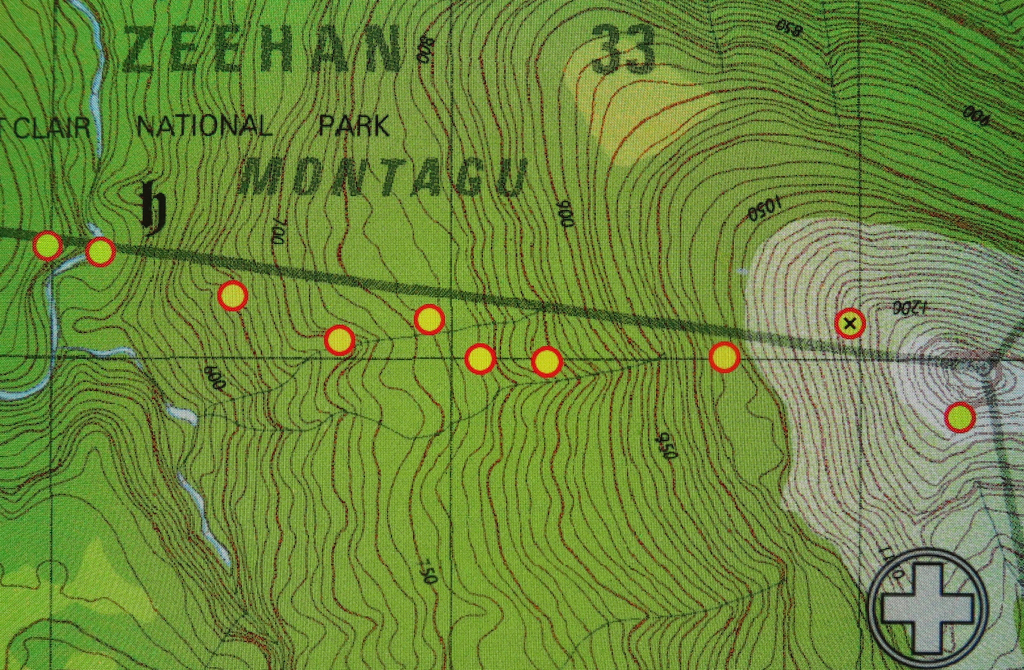

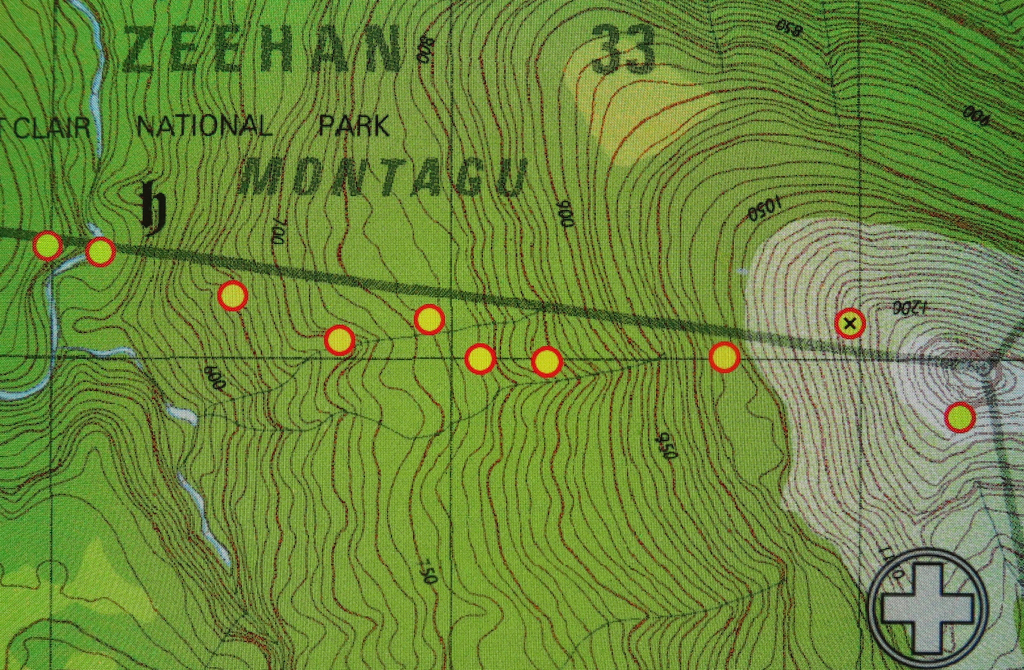

Route between Cuvier and Manfred

Descent route off Manfred.

Pitching

Pitching Two weeks in a row, I strike a Brocken Spectre. Amazing!

Two weeks in a row, I strike a Brocken Spectre. Amazing! At dinnertime, we carted our gear to the cliff’s edge to eat perched there, staring out at a beautiful sunset unfolding while we chatted.

At dinnertime, we carted our gear to the cliff’s edge to eat perched there, staring out at a beautiful sunset unfolding while we chatted.