Climbing

I have a suggestion for you, my reader: If you would like to experience the Tyndall Ranges in fairly desperate conditions, then just give me a ring. My record is unblemished. You’ll be assured of a good adventure and atmospheric photos – and, most important of all, of fairly disastrous weather.

Cresting the top: Tyndall.

The first time I went, the waterfalls were flowing uphill; the gale blew pack covers off and made zipping up coats impossible; the tops were knee deep in water. Dying from hypothermia was on the programme, but omitted this time. The second attempt, I scored a blizzard and summited solo in a snow squall with only my gps to confirm I’d reached the black dot. On the way out, all features were obliterated, not only by the deep fog of the previous day, but also by a blanket of fresh snow hiding all underneath it. The gps said where a track should be. The ground didn’t. Dying of hypothermia was on the programme, but was again postponed. This last time, I made another attempt at this interesting way to terminate my life, but failed yet again. Here I am, the cat who comes back (so far). Let me tell you this third variation on a theme.

Molly on top

We had been scheduled for a while to do a walk this weekend in the south-west, but when I looked at the horrific forecast for Saturday (a great deal of rain), I changed plans: Let’s go to the Tyndalls. We can use the track heading upwards in any weather and save cross-country navigation and any bush bashing that may occur for the sunnier Sunday. Deal.

Salome explores a different section

The car trip there was painfully slow. There are monstrous sections of 40 kph speed limit on the B18 heading south. It took five hours to get there! I parked, eyed the dark veil approaching, obviously laden with rain, and was impatient to get our climb done before it dumped on us. It was already eleven, and I was cross at the delays. Our pace was good – Molly and Salome are nice and fit – and we were at the top, photos taken, tents pitched and eating lunch before the storm broke. We sheltered in our timely-erected havens (on the summit) waiting for it to finish. It wasn’t as bad as I had expected.

I love it up here to bits. It’ s so nice to see the view!!

By 2.30, things seemed to have cleared enough for us to decide to take on Geikie that afternoon rather than waiting for the morrow. We packed the normal emergency equipment and set out, hopeful. We made fabulous time early on, and Tyndall seemed to be a good distance behind us, Geikie getting nice and close, as it began to rain at the far side of a tarn past Lake Tyndall, down in a basin between the two mountains. Mist began to envelop us. Unfazed, we journeyed on, happy with what the watch and our eyes said about progress.

Tenting on top. Geikie in the background.

Somewhat wetter, and definitely in a space defined by the very near environs (maybe about 10 metres visibility at this stage), we decided to have a check on the gps, as we had lost all sense of where our goal might now be, and how near we were to it. I was very disappointed to see the results: having blitzed the first bit, this next section, going up and down over mini-spurs and sometimes diverting to avoid cliff lines or backtracking to get around obstacles, had been slow. We were only maybe two thirds of the way there, and we had used up one and a half hours. I did my maths. It was still possible, however. A second source of disappointment was the realisation that my gps had not tracked a single step of our journey. The screen must have been bumped, turning the tracker off. Now I’d have to navigate my way on the return journey, whereas I’d hoped just to retrace our steps. On we continued, mist thickening up, rain getting heavier.

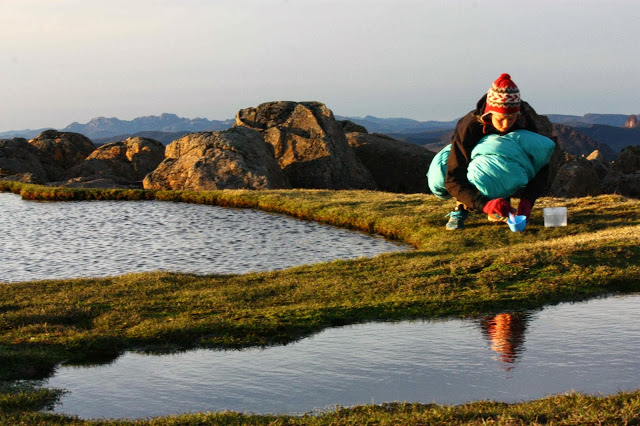

Another inspection of beauty (after lunch this time) before we set out for Geikie

Bruce and I enthused over the scenery despite the rain: we were in love with the myriad glistening tarns and their backdrop of dove-grey rocks with a pinkish hue. The girls were rather more blasé, telling us that the scenery was like the western coast of Sweden.

Now it was time to climb again: with necks bent low to the driving rain, up the slope we moiled. I gave my compass to Molly, asking her to sing out if our line drifted too much from the direction we wanted (this is often best done from behind. Bruce usually does it if we’re just two). All was well, except for the time. Our stops and checkings and decision makings were slowing us down. Now it was 4.35 and we were at a top, but not at the top of Geikie. Rather, we were on a high point (1140ms) called The Bastion, which is tall enough to be an Abel, but is not one as Geikie is next to it, and there is not a drop of 150ms between them. To get from The Bastion to Geikie, you have to descend about 70 metres to a saddle and climb again (even more). The scrub became thicker. Visibility was zero. It’s quite possible that ten metres from us there was a glorious, scrub-free route, but we didn’t have the luxury of sight.

Bruce and I were now anxious about elapsed time (and actual time). His capacities were waning. Molly in particular was all for pressing on. Her argument was that we couldn’t get any wetter, and we’d be back shortly after dark, even if not before dark. Both of these statements were true, and had it not been raining, I would have been happy to continue, but wet cold is the worst cold, so my reply was that although we couldn’t get wetter, we could get colder, and I had a man with Parkinson’s to think about. Had they not been with us, we would have turned around earlier, in fact, but I was indeed pleased to have climbed something, even if not Geikie.

One of very few photos taken on the Geikie part of the expedition – a long exposure of a tarn

The cliff line that we followed on our return journey was exhilarating with its sense of space out to our right as we made excellent speed along it, using movement as a means of warming ourselves up. Just as it was time to leave it (it swings around from the direction we needed), Bruce decided he needed more tablets to fund his motion, so we all stopped while he felt around in his daypack and did his tablet thing. I used the waiting time to photograph – just three quick snaps of nothing much, but it was the first opportunity in ages where I was stopped doing nothing and it wasn’t raining too badly. The girls were still with us, but when we turned around having packed back camera and tablets, they had disappeared. Oh well, they’d be up ahead, no doubt over that little rise just there. But when we mounted that little rise, they were absolutely nowhere to be seen. The mist closed right back in, and Molly had my compass. (We never saw them again until we reached our tent).

Sunrise from our tent window

Bruce was tired, despite his tablets (it had been a long day!), and I was going more on feel than anything else. Paper maps (which I had) are pretty useless with nil visibility, and I was unwilling to walk with the gps screen on lest I fall and break it, or run out of battery from overuse. I save it for emergencies, so headed us in the direction I felt was right. My feelings were pretty good and we didn’t go off course too much, but we definitely did not choose the fastest route, and Bruce was stumbling a bit. Time went by and it got darker. I could hear him breathing at almost a grunt each breath. I tried to jolly him along. I was ready to finish this adventure.

Same: different observer position

I checked the gps again. Yes, on vague course, but we were lower than I wanted; we had not happened on the track that existed in this area, and we still had more left to climb than desirable given the grunts I was hearing (not Azaranka level: just quiet ones, but there). A few more small falls, but we were gaining good height and at last we reached the cliffs that define the summit. But where was our tent?

Now I’ve gone back to the actual summit, 2 mins from the tent. Losing the pink. My Lee GND filter was in my pack, but I didn’t have time to get it out 🙁

I stood in the way-marked yellow dot (that indicated its whereabouts) and could not see it. We circled and circled. I began to feel mild panic when at last we saw its shape. We must have been a mere three metres away and yet it had been hidden from us by the thick soup of cloud. It was only six-thirty, but it appeared to be about eight, judging by the light.

The sun is making a valiant attempt at mounting the ridge

Next morning, Bruce had real trouble waking me for sunrise. The wind had flapped the tent all night and I didn’t fall asleep before three a.m.. I missed what he tells me was a beautiful red sky. He nearly gave up rousing me, but tried a second time and got success. I dashed outside, and luckily did get some before the sky lost all its pink and the mist closed back in for another few hours.

The descent was uneventful.

Last pink from the top. Oh how I love this place.

To bed, I wore 2 icebreakers, an O top, a fleece jacket, an Arcteryx thick jacket with hood up, possum gloves, helly long johns, O pants, lined outer pants, and 2 pairs of thick woollen socks, all inside my down bag which is good to minus five degrees. Underneath, I had a thick sleeping mat, and beneath that, a layer of carpet underlay. Then I tucked the end of my sleeping bag into one of my goretex jackets to protect the bag from moisture dropping from above (should the ice somehow melt), and another goretex jacket over my shoulders and upper torso. Over the middle section of my body, I placed my other down jacket. I was, you might say, well rugged up for this night … yet I was still cold.

To bed, I wore 2 icebreakers, an O top, a fleece jacket, an Arcteryx thick jacket with hood up, possum gloves, helly long johns, O pants, lined outer pants, and 2 pairs of thick woollen socks, all inside my down bag which is good to minus five degrees. Underneath, I had a thick sleeping mat, and beneath that, a layer of carpet underlay. Then I tucked the end of my sleeping bag into one of my goretex jackets to protect the bag from moisture dropping from above (should the ice somehow melt), and another goretex jacket over my shoulders and upper torso. Over the middle section of my body, I placed my other down jacket. I was, you might say, well rugged up for this night … yet I was still cold.