The rain began a bit before we did: lightly at first – just drizzle – but maturing into serious droplets as we climbed through the glistening rainforest, gaining hundreds of metres of altitude as we advanced. Spirits were high. We agreed the rainforest looked glorious in its shining patina and were undaunted by the moisture now covering our gear.

By the time we had reached 1200ms, just under the summit of Wylds Craig and ready to hive off northish along the spur (after two hours’ walking), the mist enshrouded us, obfuscating all features in the landscape. Our belief in the existence of a spur was a case of faith based on map evidence. There was no visible presence. My compass had a huge bubble and said that all directions were north. I ditched it. Others were to hand.

The spur was thickly bushed, with rocky knolls like giant warts along its spine. The wind from the west was fierce. We tried skirting the first apophysis to the east to evade the wind chill factor which was now making us unpleasantly cold. (The rain continued). Going over was impossible – or, more correctly, impossibly slow and dangerous, which amounts to the same thing. Unwillingly, we admitted that the bush on the leeward side was too dense. Wind was better than impenetrable scrub. Back we went and gritted our teeth for the blast, round “knoll one” which, even at nil distance, was a featureless dark blur in the grey.

Horrid as the next day was, there we all were at 7.30, battle gear on, ready to tackle the theoretical mountain to the NE. She even came to say a brief “hello”. There would be no photos for me today: my camera had got waterlogged the day before. I would just concentrate on survival and summitting. I was not feeling at all well.

Through more scrub we went, finding the odd wombat pad to help us, until we reached the magnificent myrtles of the saddle area. I had led us from the tents to this point, but handed over here to Andrew who had a compass. The mountain had once more vanished. He did a great job.

Our leader chose to attack the summit via the rocky ridge (which is the route indicated in the book), so up we all went, hauling ourselves up huge slippery (mossy) boulders, fortified by thick prickly bushes between. At one stage, we were all horrified to see Colin, who had forged on ahead, hurtling down a four metre cliff head first. We all feared / assumed we were watching death at the worst, serious breakages at the best. Somehow he flipped at the moment before landing to come to a halt in a bush, landing on his derrière: possibly the first time in history that scoparia prickles in the bum have been preferred to other alternatives on offer. His face showed the astonishment we felt when he realised he had emerged unscathed.

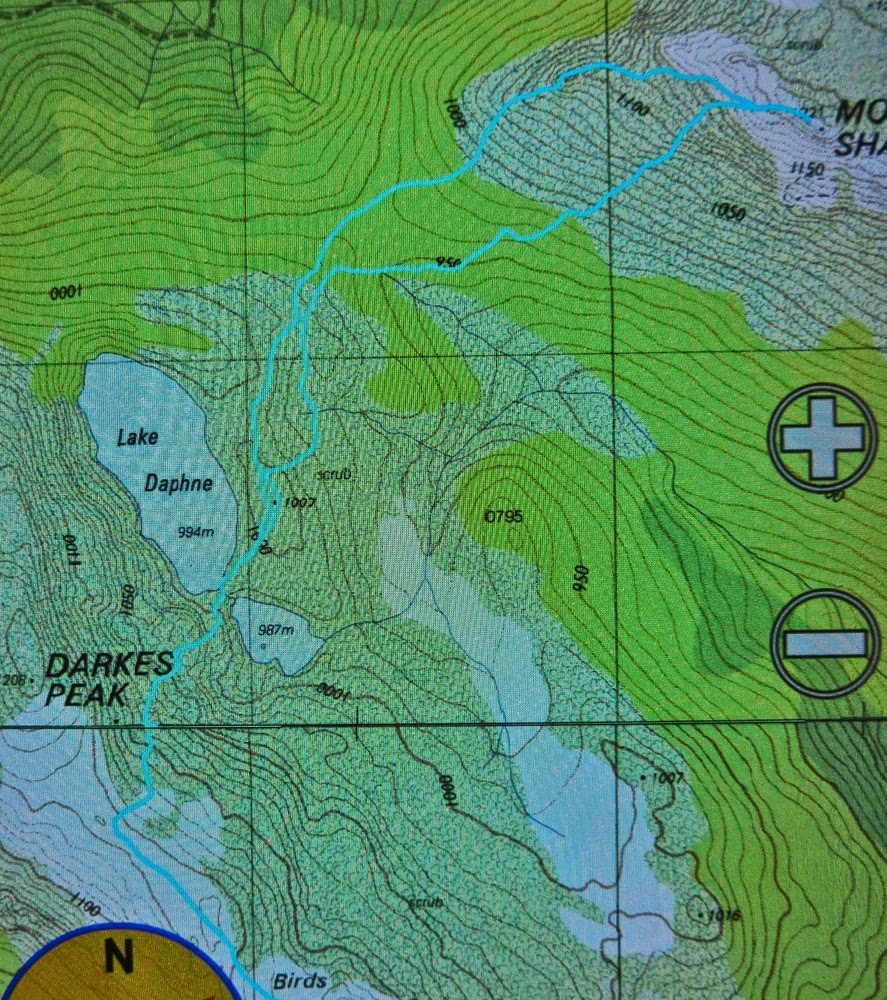

On we proceeded to crest a knoll that wasn’t the summit. I could visualise the map without needing to turn my screen on. Blast. We still had a way to go. Down. Round. Up the gully with more spaced contours. Hoorah. And then, at long last – almost unbelievably – the summit.

In my dream it had been sheer jubilation and admiration for my companions. In reality, relief was added to the mix. We hugged and thanked each other for a team effort, took happy summit shots and quitted the scene which offered no vista and a dose of wind. It can get worse. The way back was much faster as we eschewed the ridge.

Back at my tent, I felt exhausted: I must have a bug in my system. We’d only been going nearly five hours at this stage. I dismally stared down the barrel at a possible further five to get out via Darkes Peak (walking time only), and began dismantling my little home.

This time we found the pad which saved us the hour I had thought it would (48 up; 1 hr 45 down). From where we emerged, Darkes Peak was a mere 12 mins up, 9 down. It now remained to plod out the section that had taken us three and a quarter hours on the approach. We were tired, but eventually we closed off our long, hard day twelve hours after we had begun it. How lucky I am to have companions who are happy to do this sort of thing with me.

GPS data: we walked 15 km equivalents on day 1 (100ms altitude gain = 1 km equ); on day 2, we did 30 km equivalents, most of which was through thick scrub. No wonder we were tired!