View from part way up the Sentinels

Coronets Nov 2015. Day One.

I could hear Vicki up ahead:

“Break you. Break. Ach. It’s alive.”

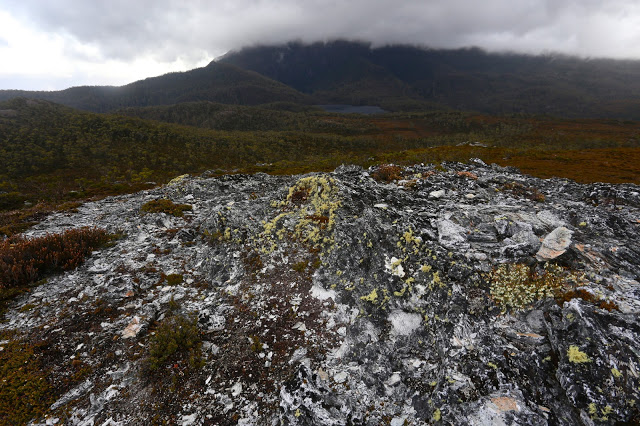

What on earth was she torturing up there? Ah. A branch. Well, it deserved it. It seemed we’d been ineffectually pushing and shoving it and its kind for an eternity. In fact, probably only three or four hours. We’d climbed the Sentinels that morning – gaining a wonderful misty view of lumps and bumps and dragon spines with white clouds swirling around us and Lake Pedder below. This was what I was here for: photography and views of this glorious landscape. Pity about the light but incessant drizzle that kept my camera securely hidden in my jacket.

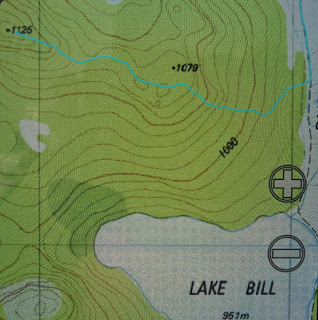

Sentinel view on the way to the summit

That ascent had been followed by a glorious traversing descent over the other side through lush, marvellous rainforest with moss that your hands sank deeply into: cool verdant glades of fairy land … but eventually all good things come to an end, and our next move was to drop further into the land of Bauera rubiodes, a shrub that, according to google, “forms dense thickets”. That is a euphemism for “forms vast, utterly impassable tangles of head high mess that leave the bushwalker exhausted”. We needed to penetrate its stronghold to emerge out the other side, but it was beginning to seem like mission impossible. However, thanks to the strength and persistence of Dale, the leader of this fabulous HWC walk, we managed, eventually, to somehow find ourselves past the unwieldy, unyielding disarray and into knee-high buttongrass and dwarf melaleucas.

Wonderful Sentinel views

The Coronets now rose visibly above us, no longer obscured by the woven basket of branches. However, it was half-past four and climbing them now seemed out of the question. Here was water, and, if you used a great deal of imagination and did some “gardening” a kind of place where pitching our tents might be possible. Well, certainly more possible than anything else we’d seen that day. We happily grabbed the opportunity and pitched away whilst the drizzle that had pursued us most of the day abated enough to let us do so in peace. Later we would hear the light patter of further rain, along with myriad birdcalls announcing the close of a wonderful day.

Day Two.

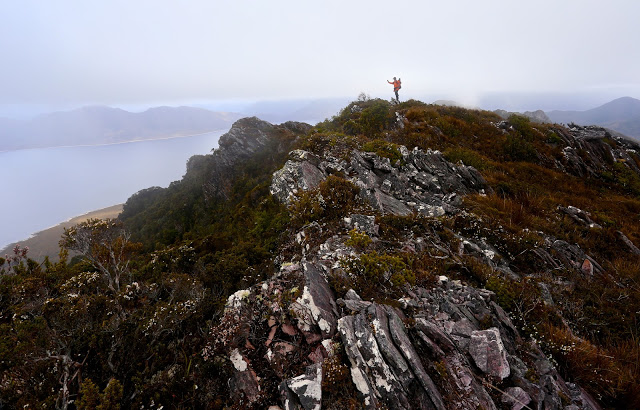

Sue crests a section that gives us a reprieve from thick scrub

Our clothes had been pretty sodden by the end of yesterday, and we had done all we could to dry them out after finishing, but it was now time to don wet items and begin our bauera fight anew. We shook our wet tents, spraying ourselves in the process, packed them up and set out up the mountain that lay ahead. The clear going we’d hoped for (and that Dale had planned for, having stared at google earth) seemed to have gone somewhere else. Progress was, once more, tough; every step a fight not only against gravity, but also against the vegetation, with a few rocky cliffs providing variety in obstacles. Packs had gained a kilo thanks to wet gear inside. It took us much longer than expected, but eventually we stood on the summit, satisfied, with awe-inspiing views to reward our efforts. In fact, the views from the various knoblets along the way had also been pretty sensational.

Nearing a false summit

When we were a portion of the way back down, the sun came out for the first time that trip, so we stopped to bask in its warmth, drying out our clothes while we did so, and enjoying our lunch staring out at the Sentinels from the day before. It was good to have a break like that, as another major battle lay ahead, and we would spend the next few hours fighting repeated skirmishes in an attempt to break through the palisade guarding Swamp Creek to win the victory of the other side, where the only viable camping spots lay. More grunts and shoves and sighs lay in store. It was almost overwhelming: at times I felt quite defeated by the impossibility of passing through.

Fabulous views during the climb

It was only quarter past three when we had won through to the other side and found ourselves in a patch of ground that could be classed as almost suitable for a campsite. We knew the likelihood of finding any other in the land ahead was nil, so eagerly grabbed our chance and searched around for places to pitch. Breaking through barricades in order to get water for dinner took a failed fifteen minutes in one direction, and a successful half hour in another. It was good to have the leisure for such a hunt, and to pitch in clement weather. Soup, cups of tea, general relaxation ensued.

But there was more thick stuff to negotiate before we could claim the summit

“Have we got as far as your day one plans yet, Dale?” He grinned sheepishly and shook his head, waving at the mountains we’d been intending to climb and pointing further away to our hoped-for spot for night number one. That had been based on discussions with others and google earth. Reality is a different matter. We all laughed at the very idea of doing that in two days, let alone one. It was a great joke. We had taken seven and a half hours that day to cover about six kilometres. This was not racing country. The pace gave us time to soak in the beauty and wildness of the region, to look around and marvel, not just at nature, but also to think with respect about the early pioneers who toughed it through land like this. Nature is not all cushy, cute and tame, moulded to suit human needs. This was wild nature, and it was fabulous.

Dale on top

Descent route – much easier going

Day Three.

Last night we all agreed to abandon our earlier glorious hopes of a multitude of mountains and bail out. There was an option that would let us climb to a saddle where we hoped to connect with the old Port Davey track that traverses this region: a marvellous historic track of great cultural significance that Parks is actively trying to stop people using so it can disappear forever! Satirists could have a field day if they had a look at where the bureaucracy of a body set up to preserve places of great beauty for the general populace has landed. We knew from other reports that this track was very overgrown, but nothing could be worse than what we’d been doing, so the track got our vote. Off we set with tents once more wet due to the overnight rain.

The way ahead – and this was a relatively clear bit, so we had stopped for a break.

Our second break was after two hours forty five (well, three for pedants) minutes’ walking. Dale had out the map and gps. Like a kid on a car trip I enquired: “Are we nearly there yet?” My admittedly cursory glance at the map had given me the impression it was about two kilometres from our campsite to the saddle. Surely after this amount of walking we’d be nearly there now.

“We’re about half way,” came the sombre reply. Oh no. We were in a dense patch of greenery, and any time we’d been given a glimpse of what lay ahead, we could see more hard work in store. We dropped all earlier plans of Possum Shed cake and coffee, and started to wonder if we’d actually get out this day.

View back down the valley in one of the interludes

We had lunch staring at the yet unconquered saddle, so near and yet so far. Dale estimated another hour to reach it. After forty minutes’ labour I looked back to where we’d dined. We’d conquered about two hundred metres at most. The saddle still appeared to lie the same distance ahead as it had been at lunch time. High to our left as we walked lay another peak, dense with dark green armour, and full of cliffs and crevices. Dale said that we had also been going to climb it in the original plan. I gave a huge belly laugh. The idea was, quite frankly, hilarious, knowing what we now knew.

Dale contemplates the exit route from a creek crossing down lower

Eventually, we did reach the saddle and found the old track. To bodies worn ragged by all that pushing and shoving, this “track” was bliss. Yes, it was terribly overgrown, and we still had to push and shove and tunnel and wonder where on earth it was, but believe me, it saved us from another night out there camped in dense forest with no spot to pitch. Our pace on the track was, by comparison with the rest of the adventure, lightning fast. There were times where you could actually put one foot in front of the other in a kind of walking motion – a most curious but pleasant feeling. Other times, of course, we had to revert to old tactics. Not being strong like Dale, I favoured a burrowing motion on the few occasions when I was in the lead. Fine for little people, but even so, the scrub was so dense that this tactic did not yield success. “Lower still”, cried Sue, watching me from behind while I crawled under the scratching web. I wriggled like a snake, but still got caught like Peter Rabbit in the thicket. Dale tore two raincoats. My overpants now come in several parts. When I got home, I could not get the tangle of forest out of my hair. Even with help, I could not undo my plait. It is now shorter, courtesy of this trip. Cutting myself free was the only solution. Thanks to the old track, we were out by four p.m. Our adventure had been fantastic, but it was also good to have it behind us.

The view from the finishing line, looking back at the alluring Sentinels. Butter wouldn’t melt in their mouths. It even looks as if we had great weather the whole time. What a cushy trip.

It is humbling to think that, had I been alone, I would right now be somewhere in that Bauera tangle, unable to extricate myself. No helicopter would land there; a rescue party would need chainsaws to reach me (machetes don’t work on Bauera). I’d possibly die of hypothermia or starvation before help arrived, if I managed to set off my PLB properly. I had been contemplating doing the Coronets solo before I saw it on the HWC programme and decided that company would be nice. Doing it with friends and benefiting from Dale’s amazing strength and tenacity made what could have been an awful ordeal into a grand and memorable life experience that I will always treasure.