Mt Bobs beaten.

“Thirteen, fourteen, fifteen …”

“Louise, you’re just showing off.”

“Sixteen, seventeen, eighteen … .” I would not be put off my leech count, flicking them as they ascended to my hands, pulling them out of my hair and off my rainjacket, overpants, gaiters and boots. The light rain that had persisted for much of the first day had certainly brought them out, but at last we were at the sinkhole, ridding ourselves of them before disappearing into our tents to try to slough off the array of wet layers and warm up before exploring our fascinating environs. The rain had ceased, and the sinkhole is a truly fabulous area.

Although we had never tried Mt Bobs and failed, both Mark and I had the feeling that this was an elusive mount: a hard capture. I had cancelled a couple of trips due to bad weather before I ever set out from home, and on one occasion we had gone to Lake Sydney, only to turn back before ever beginning the climb proper. People seem to speak of this mountain with certain tones of respect; some, even with something akin to fear in their voices (these being the ones, I guess, who had particularly long or difficult battles with thick forest on the way up). Certainly, the way is steep and the rainforest thick, and no possible path declares itself as you stare amongst the tangle and cliffs. You are too close, at that stage, to sort things out. With Bobs, I think, you need to have worked out your method of attack before you begin. Horror stories of being held captive in her thick bosky arms are not too difficult to find.

We did not treat this summit lightly, and read as much as we could before departing. In particular, we found the help of Rohan and notes he leant us from Marco to be invaluable. Thanks guys. Thanks also to Ian Ross – for our email discussions and his inspiring pictures in bushwalk.com that first sparked my interest in this mountain.

Day Two

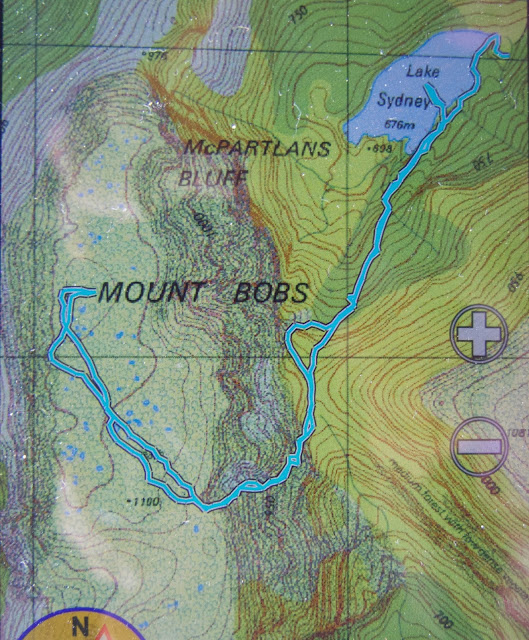

At last ascent day dawned and we stood at the start line, ready to try our luck, determined to succeed. The sinkhole was pretty full, but we could at least get around some foreshore (left) before being forced up into the rainforest by rocky cliffs. We climbed a contour or two and then progressed parallel to the lake which already seemed quite a way below us when we got glimpses of it.

Marco’s notes mentioned climbing an obvious spur. Lots of spurs can seem obvious on the map, but not so obvious when the shape is obscured in situ by thick covering, and, conversely, small spurs in the terrain can strike you visually yet be not be represented on the map, often due to the scale or the contour interval, or because they are not detected by the photogrammetry. I was standing on a spur that seemed obvious to me, but was it obvious on a 1:25,000 map with 20m contour interval? Time to check the gps. Yes. Good. Up we went. Confidence was high, and yet the notes also said that a pad of sorts could be encountered if one is in the right spot. We were seeing signs that humans might have held this or that branch, but after a while I felt like another dose of confirmation. I turned around to Mark:

“Right now, I would give a lot for the sight of a little pink tag.”

“Yes, that would be nice.”

I turned back to continue and could not believe it. There, right in front, waving at me, was exactly what I desired. It felt like we’d spotted the summit cairn. I gave a victory dance and hugged Mark with joy. This would take us on a pad that worked as far as the scrub just short of the saddle. We didn’t need to waste time with trial and error seeing if this or that cliff was going to allow us to progress on our way in this low-visiblity forest. We wouldn’t land in a cul de sac of tangle now – well, not as long as we managed to continue finding the tags. We still, of course, had to keep navigating, but every five minutes or so, you gained a pink benison: you were doing the right thing. It was a great feeling; like spiking the control at orienteering. Despite still concentrating, we could relax our guard a little now and enjoy the forest even more than we had been doing. When you are in a fairytale wonderland, that is a good thing.

We swung a bit far in the scrub before the saddle, but didn’t lose too much time, and were soon enough standing on the turn of the land, gazing up at a cornucopia of cliffs, wondering exactly which were the “obvious” ones of the written instructions. Not quite knowing, we agreed together to head for a bushy gully between two likely contenders and play it by ear from there.

Emotionally and physically, I was pulled towards the more cliffy of the two main possibilities, so when I saw the hint of a lead through the scrub that would get us to the top of it, I took it. From there, we gazed together at our alternatives. The notes had talked of cairns. There were none for us, but in this section there is visibility, so we surveyed the scene and opted to go straight up the rocky spur in front of us, reckoning there were enough low-bush connectors to get us to a gully up high that we could see, which would give us a lead through the dominating cliffs to whatever was up there beyond. We were not on THE route but this route felt good. It was, indeed, as good in fact as it was in theory and we fair bounced up to the top in a very slick time, cresting the plateaued area by 10 a.m. This was it; we’d done it. The remainder of the stroll across the tops to the actual summit – photographing, admiring the view, delighting in the tiny watercourses, patches of snow and vibrant green cushion grass patches – was almost like a victory lap after a race.

It was sunny up there as we ate a bit and gazed at Federation Peak, but we were also very aware of the gloomy weather forecast for later in the day. We had climbed in a very small window of opportunity. We thus elected not to climb the Boomerang, but rather to descend, spend a little time relaxing at the tents – even cook some warm soup to have with lunch – and head out.

When we reached the bare knoll on the way out that offers the final view of Feder, we could see it was already raining there. The clouds were quite dramatic; the front was approaching speedily and earlier than we had envisaged. The race was on. We belted down that mountain, putting in as much distance as we could before we had water dumped on us from above.

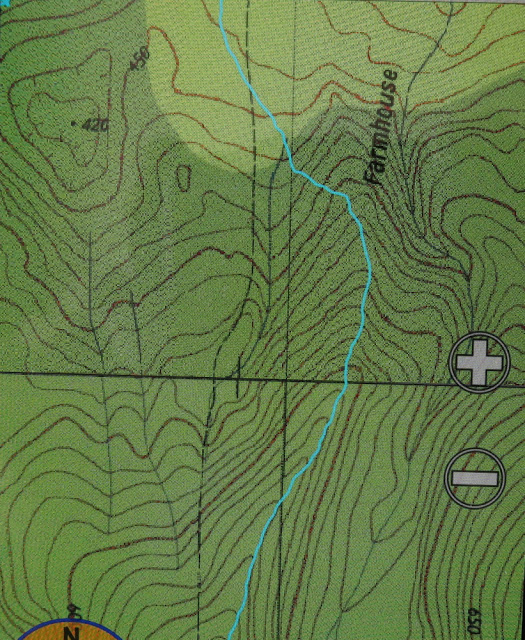

The trip ended as it began: soggy logs, covered in moisture-laden moss that drenched you if you got too close; deep mud to suck you under and wet your boots and socks; soaking bauera that made each brush with it feel like a cold, unwelcome shower; and two sodden bushwalkers. Luckily, the really punishing rains began during the drive home. We were quite wet enough with the low-intensity version of a dunking that marked the beginning of the change. Our decision to hasten out was a good one.