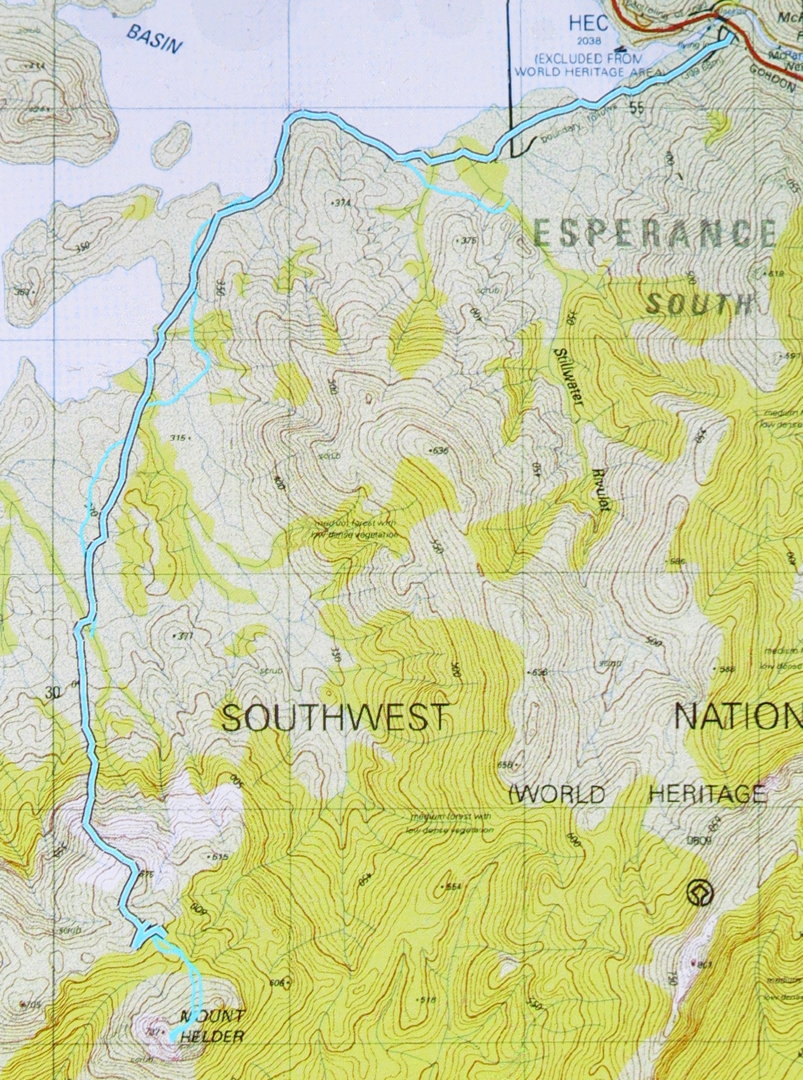

Anne Circuit 19-22 March 2015.

Day one. Lake Judd. Anyone who was superstitious would have believed this venture jinxed on the first day. My friend and fellow fun adventurer, Monika, woke up sick and had to bail out. Next, David, a friend I was going to have great fun sharing photography with, broke his wrist when he slipped on treacherous, slimy boards only 32 minutes into the adventure and had to be taken back to Hobart. Generous Phil volunteered to miss the walk and drive him. Others had to help get his pack and camera back to the car. With such an attrition rate at the start, and with rain driving down, there was a rather gloomy feel and yet those left standing remained excited about what lay ahead: the famous Mt Anne Circuit with all its mystique. We were underway at last.

And still there were seven

Because of the delays and the copious amounts of mud – with some holes on the track being over 120 cms deep (as measured by Stacey’s pole and not her body, fortunately) – the going was slow and we elected to camp down at Lake Judd rather than climbing to the base of Mt Sarah Jane. My disappointment at not being high was mollified by getting to see Lake Judd and its beautiful surrounding rainforest, and completely dissipated later as I lay snug and cozy in my sleeping bag, listening to the sound of the howling, yelping wind up high that reached us ominously down there. On the Lake, there were waves big enough for a midget to go surfing. At one point we had all been thigh deep in water. Our boots and socks were sodden and would remain so for all four days. My dripping gear lay in a ghastly pile in the vestibule; a problem for the morrow. My camera had spent nearly all day in my pack, hiding from the rain.

Day Two. Mt Sarah Jane, and a scary lesson.

Donning saturated, freezing clothes at the start of a day does not exactly cheer, but we got the job done and, shivering, set out back through the glorious rainforest to a track junction, and then up to the base of Mt Sarah Jane. I was cold and enjoying the climb, so when the others offered to let me go ahead, I accepted. This meant, however, that I got very cold up top in the wind, waiting. For most of the rest of the trip, I decided the warmest option was to be up the back or at least in the middle.

Mt Sarah Jane, awaiting our arrival. Mist is just starting to edge its way over the saddle. She looks pretty innocuous, doesn’t she. We took her for granted, so she paid us back big time.

Mt Sarah Jane, awaiting our arrival. Mist is just starting to edge its way over the saddle. She looks pretty innocuous, doesn’t she. We took her for granted, so she paid us back big time.

Once you’ve climbed up to the base of Sarah Jane, the hard work is basically done. She looks much reduced in size from that position – a wee pimple of a thing – and hardly to be taken seriously. It looked as if we’d be at the top in about 20 minutes. The others agreed to summit her too, so dumped their big packs and were ready to roll. I already had my daypack on with nibbles and camera inside. Rupert popped in his gps, which seemed almost comically superfluous. I hadn’t bothered with compass or gear. She was right there and a simple undertaking. That said, I was thrilled with the company I was keeping, that they would agree to climb in this weather. Do I need to remind you about how cold we were, having feet that were still icy, despite the climb we’d just done? The day was dull and grey; views were not promising, and an icy wind bit you every few minutes. Any normal person would have said: “Not today thanks”, and left it, but these guys said they’d come. As we set out, mist gathered, obscuring our mountain, but we knew where she was.

After maybe only five minutes’ climbing, the wind gathered ferrocity. Some blasts completely flattened me, so I climbed almost lying against the rock to prevent being tossed into space, a piece of light debris for this malicious force. Shards of sago snow bit my face and stung. Each glance back I could see the coloured shapes of the others through the dense gloom, so on we proceeded, not spreading out too much. Cairns were hard to find and I felt like a blinkered horse. My balaclava was blowing in circles around my face. My pockets had been turned inside out by the wind. On we climbed, surviving, until at last the summit was reached. Up there, I was so cold I was not coping. While we waited for the others, Stacey hugged me to try to give me some of her warmth. I was now into violent shivers. The summit photo was swiftly taken and we turned around straight away. At this stage, Peter was having trouble with his coat. The wind virtually ripped it off him so he looked like a scarecrow, the coat tails flying up above his head while only the arms stayed in place.

Spanner Lake, our tent site on night two, as seen next day from above.

Down we ventured. I was now too freezing to lead; I just wanted to be a sheep in the pack. Rupert kindly took on the respinsibility and off we set, groping our way in dense mist. Suddenly we could see neither the next cairn, nor the last two in the queue, who had, unknown to us, continued straight ahead instead of swinging around the mountain as we had done. We yelled and screamed, but the wind gobbled our noise. Rupert took a gps reading: our route lay 20 ms to the left. Boom. Batteries died. I was so cold I wondered if I would share the same fate. If we couldn’t find the others, that was a very real possibility. Every static moment made my core temperature drop a bit more, and yet we couldn’t abandon the other two. Relief is hardly an adequate word to describe the emotions on finding them. We hugged each other for warmth as Pete struggled with his coat and the rocks to join us. What had begun as the simplest of ambles up a slope had nearly ended in fatality. We all felt humbled by the unrealised potential for disaster we had narrowly escaped.

Compared to that epic, the rest of the day was gloriously lacking in adventure, and we continued on after a brief lunch to our camping place at Spanner Lake. As we crested the high point from which we would drop down to the lake, there was a glorious view of the Lonely Tarns below, surrounded by drama and magic. Gelid as I was, I wanted to capture this beauty, so I delayed the others while I retrieved my camera from the pack and they stood in the biting wind. Peter’s pack cover blew off, but was retrieved by Rupert. I got the camera out of the pack, but then spent five minutes struggling hopelessly, grunting impotently but achieving nothing: I didn’t have the strength to undo the simple clip that would open the bag containing it. No photo of that glorious scene. I sadly placed the camera back in the pack, and on we continued to our goal, which ended up being so awash that we found it difficult to find a spot in which to put tents that had not become a partial, makeshift lake.

Lightning Ridge with its gnarly, warty spine of rocks glared down at us (when the mist parted – briefly). Rain continued. Once more the revolting, and now smelly as well as sodden, gear was deposited in the vestibule while we attempted to warm up in our tiny tent havens.

Climbing Lightning Ridge

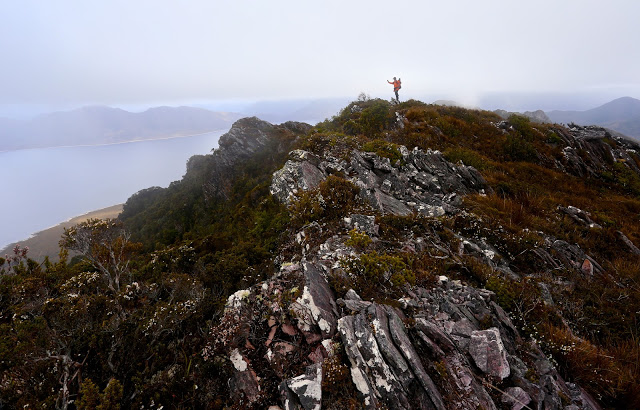

Day Three. Lightning Ridge, Mt Lot, The famous Notch. The apex; the glory.

This was one of the most dramatic climbs of my entire life. Striding Edge (UK) eat your heart out. It’s nothing compared to Lightning Ridge. Wow, what a beauty.

The day began in a prosaic enough way, like most other days: on with the putrid, sodden gear, on with the packs, no lighter despite three days’ eating due to the wetness of the tents. Off we set, over a creek at the end of Lake Spanner (whose shape I hadn’t yet seen) and up through the steep forest, knowing that the sharp ridge we’d seen from afar would be at the end somewhere up there in the heavens. Up, up we went, through glorious, but rather surprising forest: it had been raining almost incessantly, and yet, moist and lush as the forest may well have been, there was not one drop of running water to be had. I had not even thought about carrying water: it was the sort of weather in which you just pointed your open mouth upwards if you wanted a drink, but the rain had now ceased, and the strong wind must have dried out the water channels and puddles. No worries. It wasn’t a day that demanded continual drinking. I’d find water somewhere later, and I did, in a puddle in the rocks right on top.

Lightning Ridge, looking back along our exciting route

Stacey and I were together at the front, climbing away when all of a sudden we just popped out into open territory: we’d reached the rocky spine and Oh what a view!!!! Now I could see the shape of Spanner Lake, and all the surrounding dolerite pillars and mountains delicately crowned in mist. It was as steep as it’s possible to be without collapsing, and utterly mesmerising. I hate holding people up with my photography, but luckily the others were far enough behind to give me time to get out the camera and happily shoot away. I was sure they’d want a break anyway – to admire the view, even if not to eat and recharge their batteries. (Still no puddles for the negligent me).

Mt Lot, the view therefrom, and our way forward along that ridge.

The climb was protracted, which I fully appreciated for safety reasons. The times various photos were taken indicate how carefully we negotiated this supremely difficult territory – and the hard section of The Notch hadn’t yet begun. Even before we’d reached this famous stumbling block, we’d needed to do several pack passes – spots where the going was tricky, with a dangerous drop below if things went askew, and where a heavy pack hanging out the back (especially if it behaved in any way unexpectedly, if a strap got caught, or if it changed position quickly for some reason) could send the sad owner on a one way trip to eternity. On they went, off they came, as we sidled around nasty corners or inched our way up or down tiny ledges. Sometimes you’d come to what seemed a cul de sac, the way ahead thin air; the drop below, momentous. “No. They can’t POSSIBLY want me to spring down there! And certainly not with a pack on.”

At one point, we breasted a mound that I thought was “just” the high point of Lightning Ridge, but Rupert announced that we had just climbed Mt Lot. I couldn’t believe it. We were on this mountain of Great Stories. I thought it was still to come. We climbed both summits, just in case, and proceeded on our way. Our mission lay further on.

Lots Wife, as seen from Lot. He did, indeed, leave her behind.

And so, eventually, we came face to face with The Notch (to be said with a slightly quaking voice), for which Rupert had been lugging a strap and carabiner the whole way. Stacey went first, and we watched her (roped) lower herself over what seemed a bottomless pit. When my turn came and I looked over the edge, however, I could see a small ledge that held little fear (seeing’s I was roped). Yes, one lowered oneself, blind, into oblivion, but with the rope, if the fall got out of control, it would be impossible to just roll forever, and after that single manoeuvre, the rest was easy. There was not even a need for rope once that first daunting leap of faith was made. Whew. I had been rather full of adrenalin anticipating this moment.

The Notch. Sue begins the leap of faith with Rupert holding the rope for her.

Once we were all safely down, and rather elated that the worst was now behind us, up we went again, sadly needing a couple more pack removals to give us the needed momentum up slopes where our arms were just not strong enough to pull us up with the extra weight. Not all of us needed this every time, but I used this technique almost every occasion it was on offer: my pack with my full-frame camera on board was very heavy, but I did not regret the weight when I considered the shots I had already taken. Perhaps the others regretted the delays, but I was happy, despite the inconvenience of the weight. I hope the shared memories the shots provide reconcile them if they were annoyed.

Playing around on High Shelf camp, waiting for dinner time. Mt Anne featured.

On we sauntered, happy now that the rain had stopped and the wind had dried us out a bit. The sun even started to make a concerted effort to appear. Suddenly Rupert announced: Here’s our spot for the night. “What? We’re finished?” Wow. It was only 4pm. The sun was now shining. We were perched on a glorious shelf with a magic view. We turned the place into a Chinese Laundry in about five minutes flat, making a desperate attempt to dry out tents, bags, anoraks, overpants and everything else before the sun set. Hot soup was an item that urgently yelled to be on my agenda. I went across to join the others who were basking in the sun, staring at Mt Anne, brewing tea or soup. “This is the life,” I exclaimed and everyone agreed. Who cares about a few wet items of clothing when you can be here, in wilderness this glorious, staring out at sublimity in every direction? The others were drying their shoes and socks, but I knew my shoes would take a week to dry (poor boots, on their debut walk – muddy, scuffed and ill-treated), and I wanted to explore our new environs, so kept my stuff on for a few more hours. Needless to say, we were blessed with a glorious sunset. I stayed outside almost until the last light went: it was just too beautiful to be in a tent with the zip done up. I was pretty freezing by the time I admitted defeat and left the pink valley below me to its own devices.

Sunset from my tent site. The Notch is visible as the gulch to the right on the horizon.

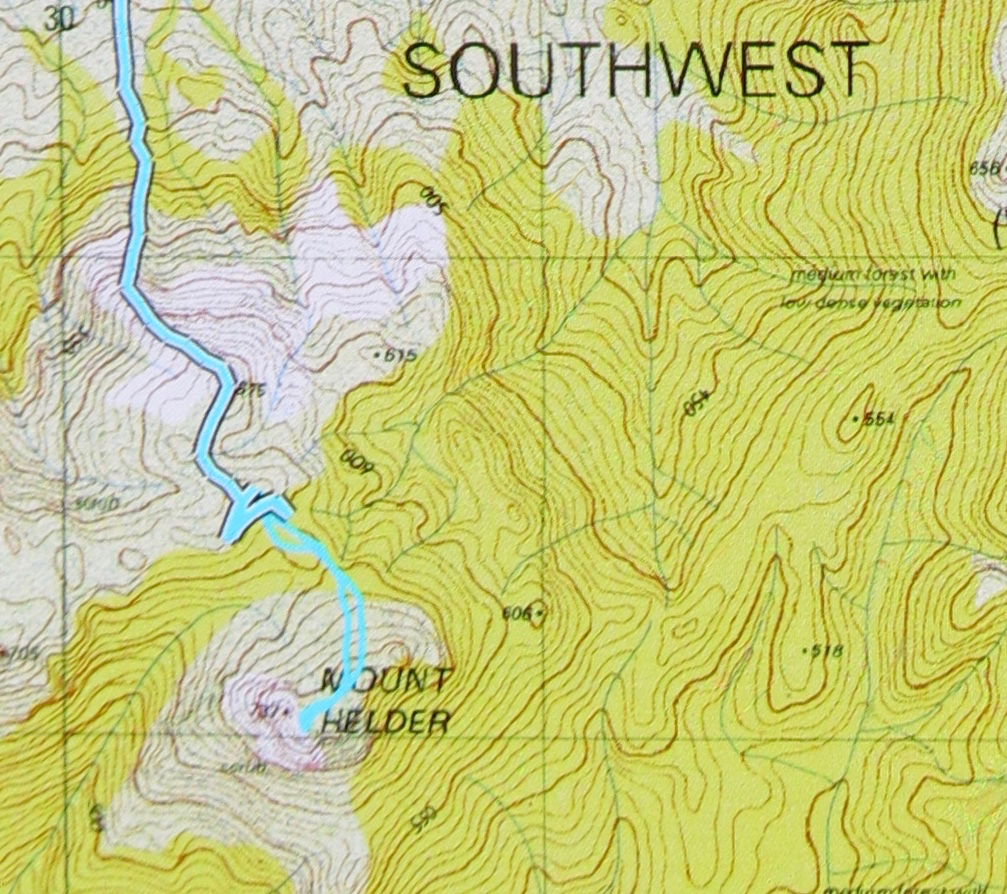

Day Four. Mt Anne for most; Eve Peak for me. Mt Eliza and down.

I was worried about the 8 a.m. departure for today, as I knew that if sunrise were beautiful, I would want time to photograph it at length. Luckily I managed to be punctual, despite being delayed by beauty. I hadn’t been so lucky during the night. I had been rather busy with mild gastro, and my frequent visits to the chilly realms outside were made worse by the fact that my tent was absolutely sodden with condensation. I was feeling very ordinary indeed, and rather weak, as we set out.

Dawn arrives at Mt Anne next morning

I am not a person who thinks that once you’ve climbed a mountain there’s no need to climb it again. Not at all. I’ve climbed Cradle six times now and am looking forward to the seventh, eighth and ninth times. Each time the view has different lighting; new features on the horizon take on new meaning. I run the Cataract Gorge route almost every day of my life and never tire of it. However, Anne has a sloping edge that I find dangerous, and I was feeling quite queasy thanks to my gastro. Meanwhile, I have never climbed Eve Peak nearby, so opted for a new peak rather than doing a walk that I find uncomfortable, to see a view that would be hazy at the top.

Off Sue sets to join the others in climbing Anne.

Anne from Eve Peak

I climbed Eve quickly, and got in a view before the mist heralding the next lot of rain started to gather strength. From the top I watched columns of mist rising, and beat a fairly hasty retreat to where I’d left my pack, remembering our Sarah Jane experience of how quickly the mist can roll in to confuse and disorient. At least this time I’d brought my compass. At about this time, the wind picked up strength again. The group had agreed to reunite on the summit of Mt Eliza. I saw no more reason for hanging around where I was. In this wind I’d prefer to be moving, so I went to our rendezvous point and hoped to find shelter. I did. Kind of. It was a long wait, but I met a few very nice people while I was perched behind a rock, and that helped to pass the time. It had been a wonderful trip: I had plenty to think about when not entertaining guests in my lair.

The final descent

The final descent