Mt Sprent, Mar 2018.

Mt Sprent was not actually my first choice for Easter, nor even my second, but, … well, let me begin at the beginning. My birthday was on Good Friday, and my wonderful (firstborn) daughter said that, as a present, she would fly down and spend the night on a mountain with me. Can you think of a nicer, more special present than that? I certainly can’t. Presence makes the best presents. Time is surely the most marvellous thing we can give each other. But WHAT mountain do you choose when given such a fabulous offer? I wanted it to be new, preferably an Abel, and beautiful. It also needed to be done in two days, as we had to be back for Sunday’s all-important Easter Egg Hunt for the children.

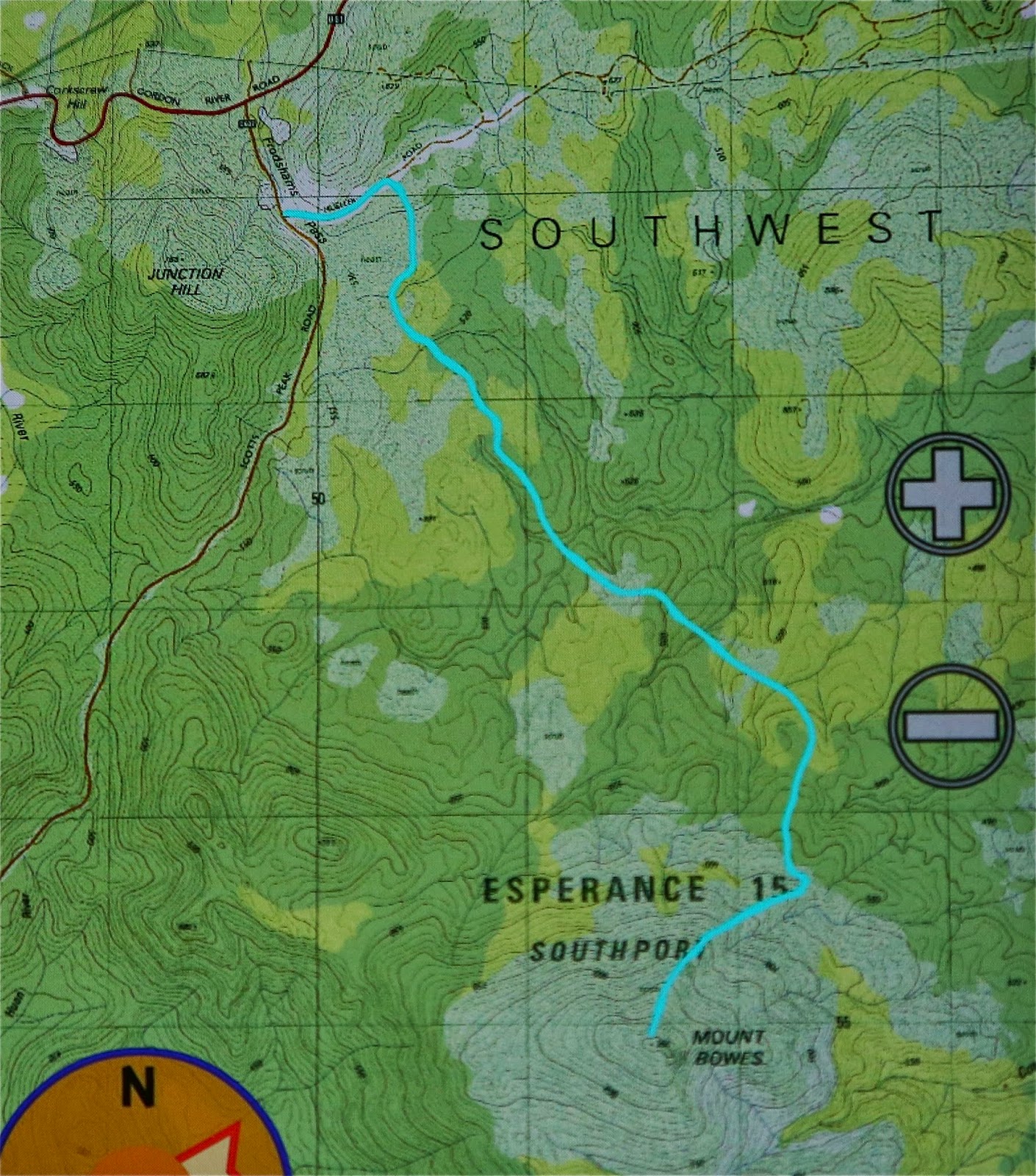

Ambitiously, I chose Bonds Craig. That was before I got a crippling chest infection and before I got news that, given all our recent rain, the Gordon River would be flooded anyway. OK. Plan B. Sharlands Peak. But, with a fever and weakness, I really didn’t think that was possible in two days either. Plan C was Mt Sprent, which I had’t yet climbed. We would hopefully get great views, and it’s just a tiny climb to the top, and even a sick Louise can do a climb that short. I was right. I coughed my way to the top, but had no trouble doing the physical ascending bit.

I picked Kirsten up from the airport on Thursday afternoon, whisked her away while Abby maintained that “Mummy’s NOT going” (how dare we have a girls’ adventure without her), and headed for the south west, with the skies getting increasingly ominous as we drove. At the sign that announced we’d now reached the wilderness area, the rain added its confirmation by bucketing down and the temperature dropped about twenty degrees. We pictured ourselves huddled in some windy shelter having the picnic dinner I’d packed and shivering while at it. Kirsten suggested we check out the Strathgordon Wilderness Lodge. Now, there’s a good idea if ever I heard one. There was room at the inn. In we hopped with glee.

Next morning (Friday, ascent day), it was till bucketing, but the forecast said the water amount would decrease after midday, so we did a rainforest walk and had a picnic lunch so as not to eat in a downpour, and set out in the afternoon. I was right about the shortness of the climb. Even with my illness, we were on the summit in two hours, and had oodles of time to find a spot for our tent on the Wilmot Range before the elements closed back in. Problem: all flat spots were a handspan deep in water, and, of course, all slopey spots were, yes, slopey. We chose the best spot available, which sloped on both the X and Y axes, and practised rolling towards each other and sliding towards the foot end of the tent before thinking about dinner.

We seem to have a bizarre sense of humour, as we found all of this rolling to be hilarious, and knew we were in for a long night. Dinner was also a bit of a problem as, since the combination of motherhood and a demanding and fulfilling job has compromised my daughter’s fitness, we were squashing ourselves into my solo Hilleberg which I carried. It’s delightfully spacious for one; for two, well, it is a solo tent. It was cuddly. I found it tricky to cook given the cramped nature of our environs, and the fact that rain was pelting down outside and we had wet gear strewn about the vestibule. I therefore cooked just one dinner which we shared between two, so my special birthday meal was half a dehydrated, rehydrated cottage pie dinner. I thanked my darling daughter for bringing me to a thousand star hotel, and we ate our fare with relish. Pity we couldn’t see any of the thousand stars.

It was, indeed, a long and giggly night. She apologised about the lack of comfort. I explained that I thought that comfort can hardly be considered one of life’s necessities. Given what we, as a family, have experienced and endured over the past few months, I think comfort is a very low priority in life. We had each other and we were happy. Isn’t that all you need?

Next morning, we descended, and reappeared at the Strathgordon Lodge in time for some freshly made vanilla slices (YUM) and a hot drink before heading east via some waterfalls to the eagerly awaiting rest of Kirsten’s family. (My second-born daughter was in Africa, so couldn’t join us this year.)