Mt Aldebaran, Apr 2018

Somewhere up there Mt Aldebaran is hiding. Looks inviting, huh?

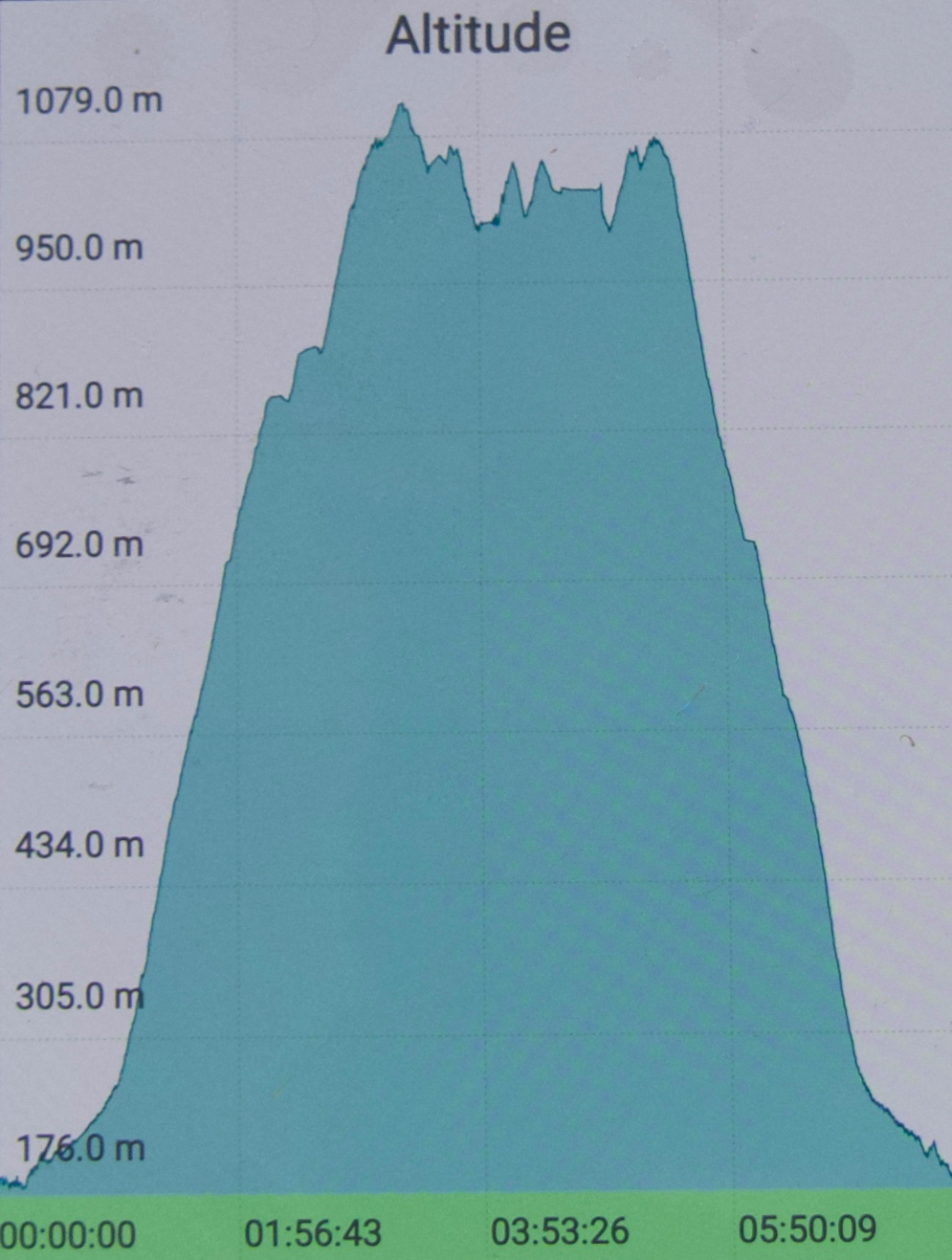

I really wanted to climb Mt Aldebaran before the super cold set in, having missed my chance over the summer. I decided it needed to be a solo venture, but thought I’d like to do it in the school holidays, as maybe I’d accidentally meet someone up on the range, and that would feel nicer. I had my plan: early start on day one, use the Kappa moraine shortcut and continue up to Lake Sirona to sleep. I’d looked at my stats for what I’d done in the area before, and this seemed feasible. Day 2 would be a shorter, easier day, just climbing Aldebaran from Sirona and enjoying being high for what was left of the day. Day 3, I would begin my descent and climb Carina Peak, dropping just as far as Promontory Lake. Day 4, out. But then I got an email from a friend saying he’d like to join in. He lives in Hobart, so starting Thursday morning suited him (rather than sleeping in the carpark Wednesday night, as I had envisaged). That was fine, although it did make reaching Sirona unlikely, but having his company – a mud buddy – would be lovely, so I agreed.

If you look carefully you can find my friend heading off into the mist.

If you look carefully you can find my friend heading off into the mist.

Day 1 did not go brilliantly. Our later start ended up very late indeed, and the track was very muddy and slow, We only made it to just past Seven Mile Creek before dark set in. I squandered half and hour at the tail end of the day trying to find a suitable crossing point for the creek that had now reached fast-river proportions. I kept going upstream until I found a fallen tree that I could hold on to. I didn’t trust myself not to be swept away otherwise. And now it was dark. Time to pitch the tents, collect water, eat and sleep. Boom. No mucking around at this end of the day. I reckon my eyes were closed by 8 pm, having got up at 4.30 to drive down to Hobart.

Up above the clouds already.

Up above the clouds already.

All night, it seemed, I pondered the dilemma of what to do with our shortened camping spot. My friend had struggled in the afternoon, and I thought getting his tent up the steep climb could take so long that we would be timetabled out of climbing Aldebaran, which would mean we had to do it on day 3, making day 4 too long. But, leaving the tents where they were and climbing up and down in a day was risky, as it would be a long day, and if we failed, then the trip failed, as there would not be enough time to then get the tents higher and start again. In the end, and with huge reservations, I decided to risk a long packless day, thinking that that would give the best chance of a summit.

A fog bow

Off we set at 7 a.m. Unfortunately, once we started on the steep section, our differences in speed became very noticeable. It was too early in the day to worry. At 9 a.m., my friend suggested I go on without him; he was not having a good day. I said I thought the worst of the climb was over, so let’s stay together longer, but at 10.40 a.m., I had to admit defeat. If we didn’t separate, I wouldn’t get my mountain, so, during the climb up out of Lake Sirona, we parted company, agreeing that I would catch him somewhere on my rebound. I hoped that’d work out.

From on Kappa moraine, looking towards Lake Promontory.

From on Kappa moraine, looking towards Lake Promontory.

Now I had two big lumps to negotiate before the climb proper began. I was so time stressed by this stage that my memory of these bumps is a blur. My whole focus was on hurrying so as to get to the summit before my turnaround time. My haste meant I didn’t make considered choices, so lost time trying to get off a cliff that was too high to leap from, but had no way around. I gave up, but on the rebound, noted wear marks leading over the edge of a different cliff. Aha. A way down around the obstacle so the climb could continue. On I went, hoping I could remember all this on the way back, when I would be equally stressed for time so as to avoid being up there in the dark.

Weee. I can see Federation Peak – that fabulous fang in tiger distance.

Weee. I can see Federation Peak – that fabulous fang in tiger distance.

Aldebaran has, it seems, four summits. Excitedly I climbed the first one, ready for jubilation, only to find two more bumps ahead, both of which seemed higher than this one. Grr. More wild dashing. At last, and getting tired now with all this frenzy, I crested the bump. It was 11.50. Oh NO. There was another, bigger bump up ahead, previously hidden behind other rocky mini-mounts. How long would it take to get there? My absolute latest turning around time was 12.30. More rushing. Hoorah. At 12.10 I stood on the summit and there were no more summits. I touched, took a few photos and thought I’d better go. To my horror, clouds, were now floating with a frenzy equal to my own, rising faster than I did up from the valley below and circling around me. I was about to lose my visibility. This was a complex mountain: i.e., this was very disconcerting news indeed. Meanwhile, it was very pretty, so I took a few more photos. Might as well die with attractive shots in the camera for my family to enjoy.

Still climbing. Looking down over Haven Lake to Mt Taurus.

Still climbing. Looking down over Haven Lake to Mt Taurus.

Mist closing in on top.

On I went, over bumps and through more saddles, hoping I’d remember my route. At the last of the bumps, I found my friend, so we descended to Sirona together. I’d made OK time back, so the pressure was easing, although A wanted to climb Scorpio. Fair enough, He hadn’t got to climb Aldebaran. He set off while I did some eating, saying I’d give chase. I caught him at the saddle before the final climb, and had great fun photographing his ascent (see below).

The route ahead. Ahem.

It had been pretty quick, and we were making good progress, so we now had what I felt were heaps of breaks, and lovely long ones, sitting on rocks watching the shadows lengthen and the atmosphere take on aureate hues as the sun dropped. Next day my friend said he would have liked more, and longer, so I guess all things are relative. At least with my being a task-master and time bossy-boot, we got back to the tents with just enough light to gather water before we lost all visibility. It was a beautiful mild night, and we both enjoyed the light and the slivered moon before falling asleep. I closed my eyes even earlier that night. I heard my friend call something about the moon from his tent, but I was too tired to even answer. It had been a long day, and I was finished.

Climbing Scorpio. The mist cleared back again by Lake Sirona.

Climbing Scorpio. The mist cleared back again by Lake Sirona.

We were both exhausted on the third and final day, and the mud seemed even sloppier and deeper. Several times we were wallowing in it thigh deep. We both became covered in its ooze, but were at the cars by 2.30, which was great, although still, by the time we’d changed out of our black, smelly gear and got going, it was too late for our favourite food places. I drove my friend to Hobart, and decided I’d go back to Maydena and use day four for waterfall and fungi bagging and shooting. I might as well use being south while I was here, and had a doggy sitter for Tessa all lined up, so I should use the opportunity while it was available. It was a good decision, and next day I would visit Tolkien Falls, Regnans Falls and Growling Swallet before the big drive home.