Mt Norold. There in my inbox was an email about a trip to Mt Norold. Mt What??? Never heard of it. Curious, I read further: plane to Melaleuca, boat up the inlet and across Bathurst Harbour, where I had never been, and then, the opportunity to explore a truly remote area of this island state. Yes please. I signed up.

Flight in

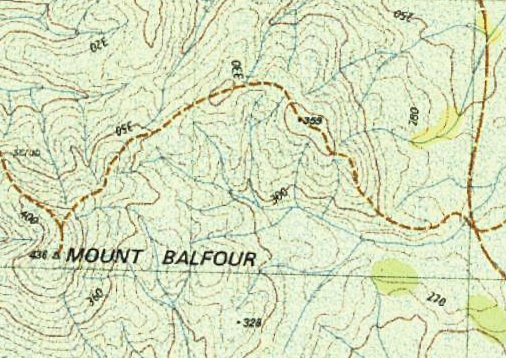

Day 1. The boat trip was very bouncy and rather wet; visibility was poor, and conditions were cool enough for me to wear both my padded and Goretex jackets. The wind was building, but, hey, we were underway, and I was happy. Progress upwards was easy, through low buttongrass, but we made slow advancement as a group, and so had failed to make our intended destination when a halt was called to the day. At this stage, we were only about 320ms above sea level, on a ridge which would, on the morrow, lead us to the top of Mt Wilson. We had nine-day packs, and some were finding the going to be tough. Three twenty metres asl is still high enough to offer fine views (if the clouds cleared); this was a pretty nice spot to stay in for the night, and offered us enough shelter from the quite strong wind. I sucked water out of a yabby hole and a small soak to fill my container, and settled down to cook my freeze-dried meal.

Day 2. The scenery remained lovely, with easy, ridgetop walking, although the outlines of surrounding mountains were murky in the slight haze. The summit of Mt Wilson was slow in the taking, and I could see we would not make our intended destination of Lake Eucryphia. (I later discovered this was no sad loss – the sides were steep and bosky). Mt Norold looked very imposing, and a long way off from the summit of Wilson.

Thus, when we were in lower-lying ground between Wilson and our goal, our leader decided it would be best if we dropped our packs and climbed Norold without them, and return later to pitch tents somewhere in that area.

Oh the joy of climbing without a heavy pack. It took no time at all to summit Norold unburdened. On top, two guys said they’d like to explore more mountains to the north, and have a look at the lake we were no longer camping at. Who would like to come too? Only Louise, it seemed. Off we set while the others returned to collect their packs and set up home for the night. It was now very, very windy.

With a walk across the ridgeline to our goal that was only decked in ankle-high vegetation, this excursion was sheer pleasure. We climbed an unnamed mountain that we christened Mount Unloved. I don’t know why it is thus uncared for, as it offered grandstand views of the Western and Eastern Arthurs, and a whole lot more – the best vista of the whole trip – and is far superior to, say, Richea Peak. The wind even abated momentarily while we were there so we could enjoy sitting and staring at our takings.

That night, we got our only sunset of the trip. Next morning, the only sunrise. Several of us sat huddled in the freezing wind, armed with several coats, waiting for the sun to go down. The wind was so biting that only two of us remained for the pinking of the sky. Next day, I was a solo observer of sunrise.

Day 3. The hour surrounding sunrise on this day was one of my favourite hours in the whole trip. I’ll let the photos do the talking:

Full of joy, I returned to the tents (I had climbed back up the ridge to take these shots), worried that I might now be running late. Today, we would descend to the Old River, to only 40ms asl, thus losing the beautiful height we had laboured so hard to achieve.

From the ridge, this descent looked stunningly steep – and it proved to be every bit as scarped as it appeared from above.

From the ridge, this descent looked stunningly steep – and it proved to be every bit as scarped as it appeared from above.

It was a tough climb, sometimes using trees instead of ground to get ourselves down, sometimes sliding down several metres of almost vertical ground, letting ourselves drop off little cliff-faces, hoping the landing would be OK.

Karen, pondering the drop to the river below, which you can see snaking through the valley.

That night was memorable, and I don’t think anyone got much (any?) sleep. It was quite frightening for some of us, actually. The strong wind of bedtime, grew to be an uncontrolled monster by the early hours, and was gusting with such force that the tent fabric was thrashing around, and making piercing whip-cracking noises every few minutes. The poles bent over towards our faces and then snapped back up, untamed wild beasts that took on a life of their own. Meanwhile, it was raining heavily. I know what it is to have a tent snap in the middle of the night in rain, so lay staring at my pole, willing it to be strong. Others were doing the same.

At 4.15 a.m., a humongous gust snapped the poles of two tents (affecting the four inhabitants). The two near me got sopping wet coping with the breakage. All four had to do repair work in the dark with rain slashing down. It was not a joyous occasion. We were all exhausted next morning, as with or without a collapse of your temporary home, the noise was not something you could sleep through. Rain continued. Our leader, full of wisdom, called a rest day (Day 5) to try to recover, and to dry out, if possible.

Day 6. See natureloverswalks.com/ripple-mountain for a blog on the climbing of Ripple Mountain.

Day 7. This was also a rest day. The rivers were swollen from all the rain, but the forecast indicated the waters may subside a bit. Our route was to take us over two rivers if we were to complete our circuit, so we needed to sit this mini flash-flood out if we wanted our other goals. Voting and discussion took place about whether to cross, how to do it safely, and what to do if we didn’t. (See photo of the swollen Old River in the blog link above). We listened to the light patter of rain on tent for much of the day.

Karen climbs

Day 8. Retracing our steps won out in the end. Several of us were unwilling to take the risks involved in a double crossing of unknown depths and strength, involving the possible (probable?) risk of hypothermia attached, especially if equipment got accidentally wet. We didn’t have appropriate gear for such a crossing.

Maureen the wonder woman, with 760 peak bagger’s points, and 155 Abels to her credit.

Up, up, up we climbed, some people hurting themselves trying to haul their bodies up the precipitous and slippery slopes. Then, down and up Mt Wilson once more, and part way down her ridge until some members of our group could just not take any more. We stopped in a spot that was pretty sheltered, considering the conditions, and had the last real meal of the trip. We had left a food stash on the other side of the river, but we would not reach it. Time to tighten the belts.

Dale, our noble leader

Day 9. On this day, we completed the descent, and chose spots for our tents on the banks of Bathurst Harbour to wait for the boat, which we hoped would rescue us early seeing’s we had no real food left. Meanwhile, this spot was so beautiful I thought paucity of food was inconsequential, and began to hope the ferry wouldn’t appear. I got my wish … and a beautiful sunset as well.

Day 10. One of the most hilarious nights of my life.

Now, this was primarily a group of pretty experienced and intelligent people, so it’s not as if we never considered the possibility that Bathurst Harbour would be tidal. It was partly tidal, we were told. We were also sensible enough to observe the water during the day. Low tide had been at 8pm that night, and we had arrived mid-morning. High tide should have been at around 1.30, just after lunch. It was nothing to worry about. We camped on magnificent grassy verges, replete with magic, crystal clear pools.

I had the most beautiful afternoon, lazing around my tent, watching the delightful private bath right outside my vestibule (it had been raining for days – of course the pools were full), and later, walking around the point for sunset, as above.

At 2.30ish, I got up to go to the toilet. My torch was on, so I saw nothing beyond its cone of glow. However, I love seeing the stars at night, so went back out without light to gaze at the Milky Way. Wow!!!! And there lay another wow: water was up to the edge of my vestibule (I could now see, seeing’s my vision was no longer reduced to a torch sector). I looked across to Maureen’s tent. Hm. It was half way up hers, but I knew she was awake, and she said nothing, so I assumed all was well. I did my maths: high tide would be 8 + 6.5 = 2.30 in the morning. OK. We were now exactly at high tide, so I’d stay awake to make sure everything (like, my maths) was correct, but all seemed to be in order.

Maureen’s island tent (at 4.15)

Shortly afterwards, Dale came along to tell us to evacuate. His tent was fully flooded, everything sopping, and he feared the worst for all of us. Maureen and I, however, elected to stay put, and “watch and wait”.

Twenty minutes later, the water was still rising, so we cleared our gear up into the trees, and sat on a rock together to watch the show.

5a.m.shot

Actual high tide came at 4.15, so we did a lot of waiting and chatting and laughing, as we thought this was terribly funny. When we realised from our little rock marker that the tide was at last on the wane, Maureen made us a hot chocolate, as neither of us wanted to return to our tents: Maureen, because hers was still inches deep in water (inside); I, because, although my inner was dry, the vestibule was still pretty sodden, and it was now so late, or early if you wish, that I wanted to hang around and photograph the dawn. We continued our vigil.

5.30. Pre-dawn glow

No one slept that night. I think Maureen and I got the most fun out of it. The boat didn’t rescue us until after 3pm, so there was plenty of time to dry out. We’ll have fodder for laughter together over that one for years to come.

Did I mention that the flight home was pretty good? (Federation Peak. That’s the one you don’t want to fall off!!)